Advertisement

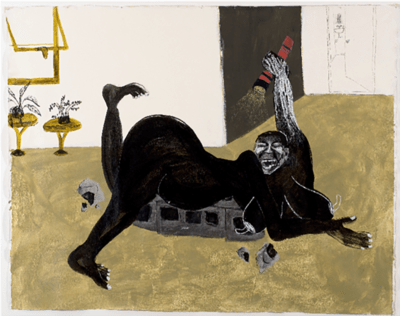

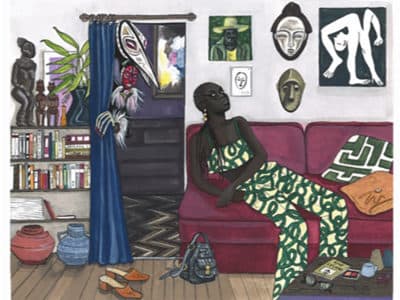

What Does It Mean To Be Black And Alive Right Now? 'Black Futures' Archives The Present

Resume

These days, deals aren't made over coffee dates, but instead by sliding into DMs on social media.

At least, that was the case for writers Kimberly Drew and Jenna Wortham.

“Our entire relationship began with a DM exchange,” says Wortham, a staff writer with The New York Times Magazine and co-host of the podcast “Still Processing.”

“I reached out. I was a huge fan of Kimberly's Tumblr and just said, you know, do you want to work on something together? And Kimberly was just incredibly gracious and generous, said yes, we had lunch, and that's really how it began.”

Now, the two creatives are celebrating the publication of their new book, “Black Futures.” It's the first in a series of books that they describe as an archive for the future.

And like all archives there's a mix of everything — photographs, poems, recipes, social media posts and music playlists — that perhaps our children, grandchildren and great grandchildren will explore to understand this current moment and what it means to be Black and alive today.

When they set out to answer that question in the book, the two women didn’t want to make a declaration but bring together voices that could help people discover the answer, says Drew, a writer, curator and creator of the Tumblr blog, “Black Contemporary Art.”

“I think for both of us, we really see this book as a launching off point,” she says, “hoping to encourage others to think about archival practices and think about what it means to sit together and really revel at our greatness and our contributions to the culture and really have a forward thinking outlook on how we all participate.”

Since the book is so non-linear, Wortham says she and Drew, along with their publisher Chris Jackson, decided to structure the book along 10 subheadings.

“It was really just [an] incredible editorial touch to help us take all the rich materials in the books and not think about them chronologically, but just organizing them into these subheaders,” she says, “so people have a sense of these tones and tempos and emotions that they're moving through that we deeply feel throughout the book as well.”

Drew says they created the book as a place where people “could really come to feel nourished,” and it’s intended for people to jump in and flip through at any time with no rhyme or reason. The book is also a physical manifestation of digital culture, creating a time capsule of social media, Wortham says.

“I love the idea of somebody stumbling upon it, like a shoebox full of memories of what we were thinking about and what we were hoping for and what was scaring us this year, I guess, in this period of time that we made the book as well,” she says.

“Black Futures” also serves a blueprint of culture for future generations to encounter and build upon, Drew says. Wortham agrees, adding that the book feels like “a testament to existence.”

“Everything about this year has felt really amorphous and ephemeral and hard to clutch onto, like I feel like I'm scrambling for perches,” she says. “Like, where are we? What year is it even? Why does everything feel so upside down? And ... it's the opposite of abstract to hold a physical book in your hands.”

The newly-published book is the first in a series, and Drew says the future of “Black Futures” lies with their audience who want to help the archive grow and evolve.

“It's with the people who really put pen to paper on those essays that they've been dreaming about and there might not be a location for, but it is completely worthy of being written,” she says. “That's the future of 'Black Futures,' and I think it's just now a matter to see what happens, and I hold hope that some beautiful things might be born.”

Cristina Kim produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Jill Ryan. Samantha Raphelson adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on December 10, 2020.