Advertisement

Author Gerrick Kennedy invites you to reexamine Whitney Houston, a decade after her death

Resume

Editor's note: This segment was rebroadcast on Aug. 9, 2022. Click here for that audio.

This month marks 10 years since we lost one of the greatest artists of our time: Whitney Houston.

From the 1986 MTV Video Music Awards to the Super Bowl in 1991, so many Houston performances gave millions of viewers around the world full-body chills.

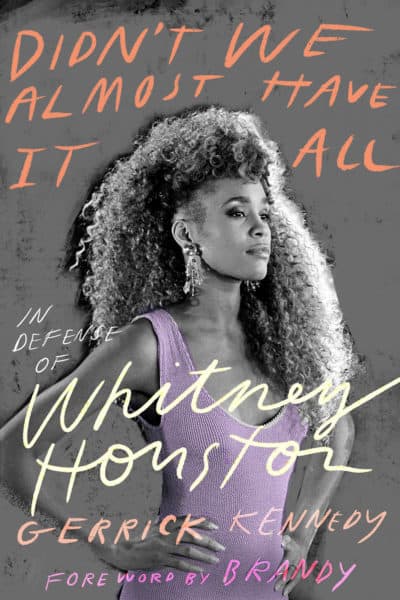

But unfortunately, it wasn’t just her voice that captivated the public eye. Houston’s addictions, relationships and identity drew harsh judgment and fueled a lot of gossip that was everything but dignified. But a decade since her death, author Gerrick Kennedy is coming to her defense in his new book “Didn't We Almost Have It All: In Defense of Whitney Houston.”

Kennedy makes it very clear that this isn’t a traditional biography. It’s “a book of cultural criticism about an artist who has not been studied, who has not been given any level of scholarship or reverence in the same way that all of the greats that she came alongside with have been offered over the years,” he says.

The book reframes the singer’s life and legacy through a lens of compassion, grace and dignity. It also serves as an examination of how society and the press mistreated her in life and after death.

Kennedy was one of the last people to see Houston before she died in 2012. He was covering a pre-Grammy event for The Los Angeles Times when he ran into Houston at the Beverly Hilton hotel. Two days later, she was found dead in her hotel room, submerged in the bathtub.

In his book, Kennedy explains how that tragedy prevented him from being able to listen to Houston’s music for a period of time: “I loved her so much, but her voice no longer reminded me of the euphoric feeling her music once gave me. In its place was regret for what could have been and deep sadness for what no longer was, and my love of her was now engulfed in guilt,” he writes.

But getting back to experiencing the joy that her music once brought was a process – one that the creation of this book provided.

“It took me down this journey of getting on Youtube and watching these old performances, seeing her in her element,” he says. “It started to help me unsee that last weekend.”

In addition to reframing Houston's life story, “Didn’t We Almost Have It All” is also a bit of an indictment of not just media coverage of pop stars but also fandom.

“We were different people then. We had a different understanding around how we consumed celebrity culture and how we consumed everything about an artist,” Kennedy says.

In that vein, he explains how people judged Houston for not meeting the unfair expectations of what we felt her music should be. She was shamed for being a Black woman — with roots in the church — who made more pop-centric music instead of the soulful sounds she was expected to continue as a descendent of the great lineage of artists including her mother, Cissy Houston, Aretha Franklin, Dionne Warwick and Darlene Love. And these expectations came from Black and non-Black people alike, says Kennedy.

Houston’s 1985 hit “How Will I Know” was the epitome of the kind of music executive Clive Davis wanted her to make to appeal to wider, whiter audiences. But that sound would propel a complicated debate about her identity. Was she trying to act white? Did her relatively lighter skin make things easier for her?

Was she Black enough?

Some didn’t think so. Rev. Al Sharpton called her “Whitey” Houston and some Black deejays wouldn’t play her records. She was even booed at the 1989 Soul Train Awards.

And others didn’t acknowledge Houston’s racial identity at all. Kennedy says he’s been criticized for parsing through the racial complexities of her story.

One self-described white woman wrote to Kennedy saying that Houston never experienced racism because “she was loved by the world,” and “we did not look at her for her color or her race,” he recalls.

“Not only is it untrue, but it's allowing you to have this almost distance from the reality of what it must have been for this young Black woman,” he says, and erase her Blackness.

It was an issue Houston was well aware of. In 1996, Houston told Katie Couric, “You’re not Black enough for them … You’re not R&B enough. You’re very pop. The white audience has taken you away from them.”

Kennedy says Houston repeatedly addressed this issue because every time she was asked about it, people didn’t listen.

“There's something so violent in that action of just constantly asking a person to defend how other people perceive them in their music,” he says.

Even in the years after her death, that judgment and shame have served as a distraction from the conversations that should be happening about her artistry, Kennedy says.

“We just saw her as this empty vessel who, yes, is a great voice, but it was ultimately destroyed by drug use,” he says. “And so we don't celebrate all she was while also acknowledging all she was not.”

Beyond Houston’s racial identity, her sexuality and her intimate relationships also sparked tremendous speculation and gossip.

Houston’s relationship with R&B singer Bobby Brown was a strategic response to the questioning of her Blackness, Kennedy says.

“This is someone who was seeing our chatter and this decided, ‘well, let me go get with this Black man in order to get this street cred,’ ” he says. “Honestly, that to me was what was appalling … the fact that we allowed that to happen for as long as we did.”

Houston was also met with anger by the press, particularly men working in radio, over her reluctance to publicly discuss her relationships. Kennedy says the culture then empowered the press to assert that celebrities needed to answer every inquiry or be met with anger.

Then, there were whispers about her intimate relationship with Robyn Crawford, her longtime friend and assistant. After Houston’s death, Crawford wrote a memoir in which she opened up about her sexual relationship with the artist.

But Kennedy says even the smallest inkling of it back then drew outrage from men in the press.

“It really did become almost a violent relationship between their lust for her and her refusal to engage it,” Kennedy says.

Unfortunately, Houston endured sexual harassment even more callous.

Kennedy recalls an appearance Houston made on a French television show in 1986. Houston, then 23, sat on a couch next to French singer Serge Gainsbourg, who in a nonchalant manner said “I want to f*** her”. Houston instantly expresses shock and disgust as the host tries to back his way out of the situation by over-explaining possible reasons for why Gainsbourg would say such a thing.

Today, that wouldn’t be tolerated — but it was then, Kennedy says.

It was a time when our society allowed for the public objectification and sexualization of a young woman and accepted the ridicule of a beloved artist burdened with enormous expectations.

And it’s not to say that our culture is completely absolved of it now.

But in the 10 years since Houston’s death, Kennedy says the way we view and understand celebrity has changed drastically, which makes this an opportune time to reexamine her struggles and the way we treated her.

He also notes that within a seven-year period, the world lost Houston, Michael Jackson and Prince to drug use before we understood how to view their addictions with compassion.

“I do think that we’re shifting toward something different,” Kennedy says.

In reflecting on his personal admiration for Houston, Kennedy recalls the last thing he told her before she died was how much he loved her music. Although, “Didn’t We Almost Have It All” would really be the last word.

“And that to me, I feel, is the greatest offering I could have given to any artist that I respect, just as a cultural critic,” he says. “The totality of who she was, I thought that needed a moment of scholarship and reverence.”

Ciku Theuri produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Chris Bentley. Theuri also adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on February 15, 2022.