Advertisement

Episode 6: 'Befriend And Betray'

Resume

When it comes to recovering stolen art, Bob Wittman’s your man.

He began his career with the FBI in 1988 — before art theft was seen as its own area of investigation. It had been classified the same as any type of property theft.

Wittman had learned the ins and outs of buying and selling art from his father, who owned antique shops. At the FBI, he showed an aptitude for undercover work. Combined, those skills set Wittman apart in the art of recovery. During his career, he helped formulate the first Art Crime Team at the FBI — and got back $300 million worth of art and cultural property.

But Wittman wasn’t able to recover two of the stolen Gardner Museum masterpieces. He was close — by his estimates, very close — to a recovery when an obstacle he hadn’t counted on got in his way.

In 2006, Wittman went undercover in Miami for what the FBI called "Operation Masterpiece." He was going on the information that a dangerous Corsican gang had a Rembrandt and a Vermeer that was stolen from a U.S. museum two decades ago.

Wittman went by the name of Bob Clay, a shady art dealer in the market for the stolen masterpieces. He befriended a pair of Frenchmen — Sunny and Lorenz — with ties to the Corsican gang, spending months cultivating their trust. Eventually, the three men made a plan. Wittman, as Clay, offered $30 million for the two stolen masterpieces. Sunny, on behalf of the Corsican gang, accepted.

The sale would take place in southern France.

Since the heist, the FBI’s Boston office had controlled the Gardner investigation. Now they had to work with French operatives — and on French turf. It began to go south when, according to Wittman, a Boston supervisor made a demand: He wanted to carry a gun. That wasn’t allowed, even for most law enforcement, in the country.

If there wasn’t much they could agree on, both the Americans and French could at least agree this was a lead worth pursuing. So after 16 years, there was at last a plan in place to recover at least two of the stolen Gardner artworks. But then, according to Wittman, the Boston supervisor canceled it abruptly. He cited vague security concerns and wanted to pull Wittman off the case entirely.

Wittman says this was the best lead the FBI ever had in the Gardner investigation. If that’s the case, then why would the Boston supervisor call it off? And why would he want to pull Wittman, who many agents hold in high esteem for his art recovery abilities, off the operation?

Subscribe to our newsletter for the latest updates, join our Facebook group to discuss the investigation and if you have a tip, theory or thought, we want to hear it.

This episode was adapted for the web by Amy Gorel.

Transcript:

KELLY HORAN: It’s not everybody who can recover stolen art. Having a tolerance for con men is helpful, because you’ll be spending a lot of time with them. You need to have patience — a lot of it — because these things take time. And you have to have both a knack for building trust and a comfort with destroying it.

BOB WITTMAN: You know, in every operation that an agent goes undercover his main goal is to befriend and then betray. That's the whole point.

HORAN: This is retired FBI art recovery agent Bob Wittman. He spent his entire career based in the Philadelphia bureau — about two decades — befriending and betraying as a job description. It was all in the name of recovering hot art. By his reckoning, Wittman has gotten back some $300 million worth of art and cultural property: Geronimo’s eagle feather headdress, a ring with a lock of George Washington’s hair in it and precious artifacts thought to be lost forever.

WITTMAN: Including documents such as an original copy of the Bill of Rights that was stolen by a Union trooper in 1865 from the state of North Carolina.

HORAN: But the most valuable — and elusive — art that Wittman says he was this close to recovering, was stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in 1990.

JACK RODOLICO: Wittman’s account of how those masterpieces slipped away offers a master class in how to plot to get stolen art back, and also how to blow it entirely. And in a tale with roadblocks to spare, was the Boston FBI one of them. Did they sabotage Bob Wittman’s efforts to recover the Gardner art?

HORAN: From WBUR Boston and The Boston Globe, this is Last Seen. I’m Kelly Horan.

RODOLICO: And I’m Jack Rodolico. This is Episode 6: "Befriend and Betray."

Our story begins in 2006 with Bob Wittman, undercover, befriending a pair of French gangsters with ties to a murderous Corsican gang.

WITTMAN: The actual information was that they had paintings that were stolen two decades ago from a museum in the United States. And one of the paintings was a Vermeer and the other was a Rembrandt.

RODOLICO: The Vermeer really piqued Wittman’s interest because at the time, there was only one missing: "The Concert." In Miami, Wittman adopted the persona of a shady art dealer in the market for stolen masterpieces. He called himself Bob Clay. And he began to spend a lot of time with two Frenchmen. One was named Sunny. The other, Lorenz.

WITTMAN: Lorenz was a French national who was living in Miami. He had done well in the real estate business. Drove a Rolls-Royce. He had his hair well-coiffed. He went and got facials. He had his nails done on a regular basis. Sunny was the exact opposite. Sunny was short, very squat, all muscle from the neck to the waist, but he had a big waist. He was heavy. He had a haircut, uh, what they call those — the long in the back and short in the front?

RODOLICO: A mullet?

WITTMAN: Mullet, yeah.

RODOLICO: Both men — Lorenz, well-coiffed, and Sunny, rocking a mullet — had serious criminal records back in France. Sunny’s rap sheet included charges like theft, drug trafficking, aggravated assault. Lorenz was allegedly on the run from charges for financial fraud.

WITTMAN: In the end we found that Lorenz was basically more like a mob accountant, whereas Sunny was more like the hired muscle.

RODOLICO: Wittman, posing as Bob Clay, spent months cultivating their trust. As he did, he says he grew increasingly persuaded that Sunny and Lorenz held the keys to getting the stolen paintings out of France, where they were allegedly held in the hands of that Corsican gang.

HORAN: It was a gambit that could have cost all of them their lives. Those Corsicans were stone cold killers. In order for his Operation Masterpiece, as the FBI called it, to succeed, Wittman had to secure Sunny and Lorenz’s unwavering trust.

One day, the three men met in a Miami cafe.

WITTMAN: And Sunny said, "OK, we're going to do this operation, but we're going to have to set this up in a triangle." And he took a little piece of tissue, or a napkin, and with a pen he wrote a triangle, and he said, "This is a closed triangle. It’s just three of us. This is a Triangle of Trust. If anything happens, we'll know it's one of us was the informant."

HORAN: As Sunny drew his Triangle of Trust, he wrote each man’s initials in each corner — B, L and S: Bob, Lorenz, Sunny. Three strangers pledging their trust to each other and to one goal, an art sale. But not just any art sale, a $30 million black market swap of cash for two stolen masterpieces. Wittman and other former federal officials we spoke with say this was the best lead the FBI ever had in the Gardner case. They also say that Bob Wittman was, hands down, the best, the only, man for the job. No one else had his background, his eye or his expertise.

RODOLICO: And Wittman says he's been an art lover since he was a kid. He grew up in Baltimore. And his parents met during the Korean War, when his dad was stationed on an air force base in Japan.

WITTMAN: That's where he met my mother, married my mother who was Japanese, working on the base, and he fell in love with all things Japanese at that point. And I grew up around these antiques. When other people were throwing footballs in the house, I was looking at Japanese Satsuma, and Kutani ceramics, and looking at Ukiyo-e prints.

RODOLICO: After the war, his dad opened three antique stores. And it was in these stores that Wittman learned how to buy and sell art — skills that would later serve him well. He started at the FBI's Philadelphia office in 1988. Back then, there wasn’t really a job designed for an aspiring art cop.

WITTMAN: Art theft back in 1988 was considered the same as any type of property crime. It didn't matter if it was a Chevrolet or a Monet. It was the same. So there was no professionalism involved in how to do an art theft investigation in 1988 when I started.

RODOLICO: Over time, Wittman gravitated to cases that spoke to his love of art and antiquities. He linked up with Assistant U.S. Attorney Bob Goldman, who helped him find legal avenues to pursue cases of stolen art. Goldman says Wittman solved bigger and bigger art crimes because he was so smooth undercover.

GOLDMAN: Even knowing he’s an FBI agent, I would buy heroin from him 'cause he was able to sweet talk you and he did it with dignity. He used to keep pictures of some of the guys that he used to arrest. And he had pictures of himself and the guys smiling and shaking hands at the time of the arrest. I mean they actually liked him.

HORAN: One of Wittman’s bosses Eric Ives, a retired FBI supervisor, says Wittman’s successes helped convince the FBI that they should be doing more to solve art crimes.

IVES: Bob Wittman, in a football analogy, was the quarterback. He had the experience and expertise and, unusual to many programs, Bob not only had the art expertise, but he also was an undercover agent. So it was a rare opportunity for us to take advantage of his skill set. And so he was the thinker or the creator of the idea to create an Art Crime Team.

HORAN: Wittman’s work relied on a basic truism of art crime: Stealing the stuff is easy. Selling it is the hard part.

WITTMAN: These individuals are not always well-versed in the business of art. If they were they wouldn't have stolen what they stole. I mean, there's no way you're going to steal a Rembrandt from the Swedish National Museum and be able to sell it on any kind of market.

HORAN: Bob Wittman would know. He’s the one who recovered that $35 million Rembrandt. He bought it in a dingy, Danish hotel room in 2005 from an Iraqi criminal, who was promptly arrested after the sale. When Wittman went undercover, he never wore disguises. He didn’t use fake accents. He had a rule.

WITTMAN: Try to keep everything as true as possible. In other words, you don't have to remember the truth. So remembering lies is much more difficult than just remembering the truth.

HORAN: Wittman might have been posing as a shady dealer, but he told the truth about where he grew up, how many kids he had and what kind of art he liked. And he always used his first name, ensuring he would react naturally. Like the time he met a criminal carrying a stolen item in an airport.

WITTMAN: And as we walked through the airport there was someone there who actually knew me, a neighbor, and who said, "Hello, Bob." And it was perfect. So my response was, "Hey, how are you doing, Jeff?" And we kept walking.

RODOLICO: Does an unplanned moment like that, sort of, deepen your credibility in a criminal’s mind, right, when they see you sorta being vouched for?

WITTMAN: That's a possibility, but I can tell you for a fact: Moments like that are terrifying, and they make your rear end slam shut because of the, the moment that you might be found out.

HORAN: One of those moments came when Wittman watched in horror as some fellow undercover FBI agents went too far.

RODOLICO: Talk about the strawberry eating contest.

WITTMAN: Nah, I don't want to talk about that.

RODOLICO: Really? Even though it's in the book and you've talked about it already?

WITTMAN: Eh, I don’t like talking about that. Yeah, I don't want to talk about strawberries.

HORAN: Wittman doesn’t want to talk about the strawberry incident, but we can because he wrote about it in his memoir.

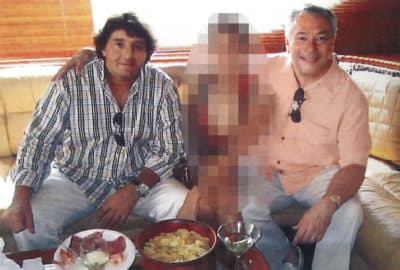

In 2007 the FBI rented a yacht in Miami for a party — the kind of party a black market art dealer like Wittman’s alias Bob Clay might attend. Other than the criminals Sunny and Lorenz, everybody on the yacht was FBI — the Captain, Colombian drug dealers and their bikini clad wives. All agents. Wittman haggled with a fake drug lord over the price of some presumably stolen paintings — in fact they were FBI stock forgeries of works by Salvador Dalí and Georgia O’Keeffe. All of this was for the benefit of Sunny and Lorenz so they could see Wittman, aka Bob Clay, in action.

Wittman played his role, but he says the other agents on the yacht over-acted theirs. The drug dealer wives suggested a strawberry eating contest. Then, to Wittman’s dismay, they got down on their knees and started sucking whipped cream off the strawberries, and they designated Sunny the judge. Wittman wrote, “It didn’t play right — the chubby, lowest-ranking guy in our gang getting the royal treatment. Sunny fidgeted uncomfortably. Once again, our investigation was veering dangerously off course.”

Wittman thought that was bad enough. What came next threatened to derail the entire operation.

RODOLICO: So, quick recap: Bob Wittman, posing as Bob Clay, the kind of art dealer undaunted by the prospect of handling some of the world’s most famous stolen paintings, was in Miami, trying to buy them. The more time Wittman spent with Sunny, who represented the Corsican sellers, and Lorenz, who was brokering the deal, the more Wittman became convinced that they really did have two of the Gardner Museum’s most prized stolen treasures: "The Concert," by Vermeer, and Rembrandt’s only seascape, "Storm On The Sea of Galilee."

WITTMAN: You know, throughout my career it's been my, my, I guess job, my training, my experience to identify individuals, to see if they're lying. Identify if what they're saying is true. And for Sunny my radar was up in the beginning, of course. But, I believed what he was saying because he was basically saying what he had heard. He was parroting what he was told. He wasn't actually, you know, puffing. He didn't say he had 50 paintings. He said he had two — one by Rembrandt, one by Vermeer.

RODOLICO: He offered $30 million for the paintings. On behalf of the Corsican gang, Sunny accepted, and then informed Wittman the sale would take place in southern France. French and American law enforcement got to work; they met in an art museum in Paris to devise an undercover operation in France. On one side of the table, the French. On the other side, the Americans.

WITTMAN: And as we discussed this operation the French were starting to buy in.

RODOLICO: As it has since the day of the heist, March 18, 1990, the FBI’s Boston Field Office controlled the Gardner investigation. And so agents from Boston were at the meeting in Paris, too. Wittman remembers one in particular — an agent he describes as the head of Boston’s bank robbery and violent crime squad. From now on we’ll refer to him as the Boston supervisor. Wittman says the meeting took an awkward turn when the Boston supervisor made an outlandish demand.

WITTMAN: He wanted to carry a gun in France, which is not allowed.

RODOLICO: He was on foreign soil, insisting that when the undercover sale went down, he and his agents be armed.

WITTMAN: So here he is representing the United States, in a very sensitive, possible undercover operation to recover some of the largest, valuable objects, ever stolen in the United States, and he's demanding, basically, to be able to do things that he can't do.

RODOLICO: Wittman says the Boston supervisor didn’t seem to understand that most French police don’t even carry guns. More than that, he seemed to be trying to throw his weight around in another country because he was in charge of the case.

WITTMAN: Which really was kind of an embarrassment. That set the tone for the rest of the investigation as to his experience and ability in these types of cases.

RODOLICO: Wittman will talk about this guy, but he won’t name him. Others we spoke with who have knowledge of Operation Masterpiece won't name him either. The Boston FBI has refused our requests for an interview, so we can’t confirm his identity. If there were an impasse over who would go undercover — Americans or French agents — everyone involved in the negotiations seemed to agree on one thing: This lead was worth pursuing.

WITTMAN: During that period of time, too, the French National Police, they had wiretaps on phones that Sunny was using. And they heard Sunny talking on the wiretaps about — in code about the Vermeer and the Rembrandt.

RODOLICO: Do you remember what the code was?

WITTMAN: He was talking about apartments, buying apartments on Vermeer Street and Rembrandt Street.

HORAN: The push and pull between the French authorities and the FBI in Boston and Philadelphia aside, Wittman’s triangle of trust remained intact. Even as his role in a planned sting was in question, Wittman never lost momentum with Sunny and Lorenz. They set a date for the sale of the Vermeer and the Rembrandt.

After 16 years, there was at last a plan in place to recover the stolen Gardner art. At least some of it. But then, Wittman says, the Boston supervisor canceled it, citing vague security reasons. Next, he told Wittman that he was thinking of pulling him off the case entirely, replacing him with an agent from Boston.

Why would the Boston supervisor do this, if Wittman was the art recovery guy at the FBI, and if he had cultivated sources who had gotten him this close to what promised to be a recovery of the stolen art, why would he undercut the whole thing?

DAVE HALL: It was a high-profile case where there was a lot of, you know, potential for glory. Individual glory. And that’s when people in the government are at their worst. The job isn’t to get into the newspaper.

HORAN: This is Dave Hall. At the time of Operation Masterpiece, he was the prosecutor assigned to the FBI’s Art Crime Team. Hall says it wasn’t just Boston’s wanting to control the case. It was about something that’s not supposed to be a factor, but totally is.

HALL: How can personal glory trump your duty? The hypocrisy and the, you know really the failure to live up to a sacred oath makes this kind of problem particularly bad. It's the kind of conduct that should really be avoided at all costs.

RODOLICO: What exactly is the cost?

HALL: Unsolved crime.

HORAN: About six months into Operation Masterpiece, something else happened that would mark a low point in Bob Wittman’s FBI career. It’s something he and his colleagues are still reluctant to talk about. It’s almost mundane, except that it’s the office equivalent of a back stab. The knife in Wittman’s back was a memo. It was written by the Boston supervisor and sent to FBI headquarters in Washington, D.C. It also went to Wittman’s old boss, Eric Ives.

IVES: And the memo that was written about Bob Wittman was not accurate. I mean, I don't want to get into the specifics of the memo, but, you know, we rely on our integrity in the FBI and so it goes to the heart of integrity.

HORAN: Our colleague from The Boston Globe, Steve Kurkjian, says the Boston supervisor’s memo was designed to inflict maximum damage on Wittman.

KURKJIAN: This kind of memo would have been so dangerous, so destructive, to the investigation. All he had to do was send it. He knew what he was doing. It was gonna to sabotage it and it served its purpose.

RODOLICO: So, what did this memo say? It charged that Wittman was working this Gardner lead because he wanted to collect the reward offered by the museum.

WITTMAN: Saying that I was involved in the case 'cause I wanted to try to somehow claim the reward.

RODOLICO: So you're saying that the Boston office claimed to the D.C. office that you, Bob Wittman, were trying to get $5 million — the $5 million from the Gardner Museum. What did you think?

WITTMAN: It was disgusting and frustrating.

RODOLICO: As an FBI agent working the case, he wasn’t even eligible for the Gardner’s reward. More to the point, Wittman says the memo was slanderous.

How was that memo received?

WITTMAN: Ultimately, it was withdrawn. So that tells you how it was received because they wouldn't have withdrawn it if it had been accepted. It was unacceptable.

RODOLICO: Wittman says the Boston supervisor was told to withdraw the memo — by headquarters. But its damage was done.

HORAN: This is a story that makes Bob Wittman look like both a victim and a hero. It’s a story that has served him well — he’s sold a lot of books. He’s given paid talks. And he’s enjoyed an international profile as an art crime expert. But he’s essentially accusing the Boston FBI of misconduct. And the Boston FBI won’t talk to us. So we turned to Anthony Amore, who’s as close to the Boston FBI as we can get. Amore is at pains to say that he respects Wittman, that the man’s record speaks for itself. But, when it comes to his lead with the French gangsters...

AMORE: They never produced one shred, not one tiny iota of evidence that they had our art other than talk. Take away the intrigue of Corsica, take away the intrigue of an undercover operation and international goings on, and then think to yourself: But they never produced anything ever that tells us they had the Gardner art. So it's an interesting story, but that's where it ends. I don't believe they were there.

HORAN: Amore was only a year into his job as the head of security at the Gardner Museum when Wittman was a senior investigator undercover in Miami. But today it’s Amore’s job to find the Gardner art. So it says something that he’s not poking around in southern France looking for it. But in the absence of conclusive evidence from the Boston FBI or anyone else, this story hinges on Wittman’s track record and his credibility. And to the people who know him best, like former prosecutor Dave Hall, if Bob Wittman says it, they believe it.

HALL: No one in the FBI had his experience as an undercover in the, you know, art and cultural property space. And nobody since. You know, he was one of a kind. So he was a really, really precious resource at this moment in time in this really important case.

HORAN: Wittman says, despite how close he was to the gangsters Sunny and Lorenz, and despite how solid the intelligence was, after the memo and the interference from the Boston supervisor, he withdrew from Operation Masterpiece. He said he had to.

RODOLICO: I mean it also sounds like you have to be able to trust your life in the hands of the supervisor in Boston as well as others. Did you?

WITTMAN: No! These departments and these agents weren't gonna have my back on this, so because of this tension we had to let the Gardner paintings go.

RODOLICO: You had to let the Gardner paintings go?

WITTMAN: Let 'em go.

RODOLICO: Wittman was off the case, but Operation Masterpiece continued without him. And the triangle of trust remained. Or so Sunny and Lorenz thought. They had no idea why their American buyer Bob Clay had vanished. They kept reaching out to him, but Wittman kept his distance until …

WITTMAN: Sunny came up with information about two paintings that were stolen in Paris. These two paintings were Picassos that were stolen from the apartment of Picasso's granddaughter.

RODOLICO: Sunny and Lorenz wanted to sell those Picassos to Bob Clay. Wittman passed the tip to French police, who set up a sting in France, arrested the thieves and got the paintings back.

WITTMAN: Total value of those two paintings was about $65 million. That was very good for the French national police. It wasn't so good for us, because at that point the information was that somehow they were turned in by the individuals in Miami. In other words, how were these guys set up? And the question was, who set them up? And the only other outsider in Miami was me. The thought there was that I was some kind of informant and that I should be killed.

RODOLICO: Two French hitmen flew to Miami and threatened to kill Lorenz. And they wanted to talk to the American. Wittman still felt himself beholden to the triangle of trust, if only because he held out hope for the recovery of the Gardner art. He went to Miami to face the French gangsters.

WITTMAN: They were introduced to me as Salt and Pepper. One was a white Frenchman the other one was a African or a black Frenchman. And in fact were known to be very violent criminals. They explained how they did most of their killings with knives, not with guns.

HORAN: This meeting was the first time Wittman ever went undercover carrying a gun.

WITTMAN: So I figured they were bringing a knife to a gunfight, and we'd see how that ended up. We went to the hotel bar. I sat at the table facing them. They were against the wall.

RODOLICO: And there's five people at that table, right?

WITTMAN: Yes. Salt and Pepper, Sunny, Lorenz, and myself.

RODOLICO: Oh, I meant six, wasn't there a sixth?

WITTMAN: Oh, yeah. And another undercover agent from Boston. That was the individual they were trying to insert into the case. And he was acting as a mobster from Boston who was somehow financing being involved.

RODOLICO: What did you really think of the idea to insert this person?

WITTMAN: Well they wanted to insert the Boston agent because they wanted to bring him in as... to overtake the role that I was doing, which is, you know, what their idea was, but he wasn't accepted because he wasn't in on the triangle. So he wasn't there at the beginning and it was very difficult to bring him in. Nobody trusted him.

RODOLICO: How did he act?

WITTMAN: He was fine.

RODOLICO: But he wasn't really fine, right? I mean you wrote in the book that he wasn't fine.

WITTMAN: I'm not going to comment.

RODOLICO: OK.

WITTMAN: I'll let the book stand on its own.

RODOLICO: What about the credit card, can you give the example of the credit card?

WITTMAN: I'm not going to talk about that. You know, look, turn it off a minute.

RODOLICO: Here’s a summary of what Wittman wrote in his book: The meeting was going well, but the agent, a guy the Boston supervisor pushed into the undercover operation, was talking like a clichéd character in a bad gangster movie, saying things like, “You deal with me. As far as you’re concerned, I am the business.”

At one point, one of the hitmen turned to the agent and said, “Who are you again?” And then, as though he couldn’t have been less convincing, the agent from Boston, with everyone watching, paid with his credit card. Bad guys pay with cash. Everybody knows that. Almost everybody.

HORAN: Already suspicious that a snitch was in their midst, the French gangsters walked away, refusing to work with the Boston agent. After nearly two years, Operation Masterpiece was over. Bob Wittman remains convinced the Gardner art was still in France by the time that operation ended. Today, he says, the Vermeer and Rembrandt paintings could be anywhere in the world.

Steve Kurkjian says he doesn’t understand why, after the alleged misconduct and mishandling of Operation Masterpiece, Boston’s FBI office today remains in total control of the Gardner investigation.

KURKJIAN: It just seems to be just the old boy way of doing things that were so well in place at the FBI's Boston office.

HORAN: If there has ever been any oversight of the Boston FBI’s handling of the Gardner case, it hasn’t happened in the public eye. With nearly 30 years gone by, you have to wonder why.

Next time, we go from a man trying to get the art back, to one who would steal it. Was the world’s greatest art thief behind the world’s greatest art heist?

Last Seen is a production from WBUR and The Boston Globe. Digital content was produced in partnership with The ARTery, WBUR's arts and culture team. Read more on the Gardner heist from The ARTery.