Advertisement

Reporter's Notebook

Bulger And The Gardner Heist — A Lot Of Speculation, And Very Little Evidence

In early 1991, less than a year after the stunning heist at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, recently retired Boston FBI agent John Connolly got a phone call from one of his former bosses, asking for his help on the case.

The Boston FBI, which was and still is in total control of the Gardner investigation, had run out of immediate leads. Connolly's former boss, according to a source close to Connolly, asked if he could reach out to James "Whitey" Bulger to gain his assistance.

Connolly had long handled Bulger as a confidential informant for the FBI. That secret alliance allowed the South Boston crime boss to become the city's deadliest gangster during the 1970s and 1980s. But his reign of terror ended in late 1994 when Bulger was indicted for multiple murders and racketeering. Four years later, Connolly, too, was indicted on racketeering charges and for tipping off Bulger that he was about to be arrested, which allowed Bulger to flee capture until 2011.

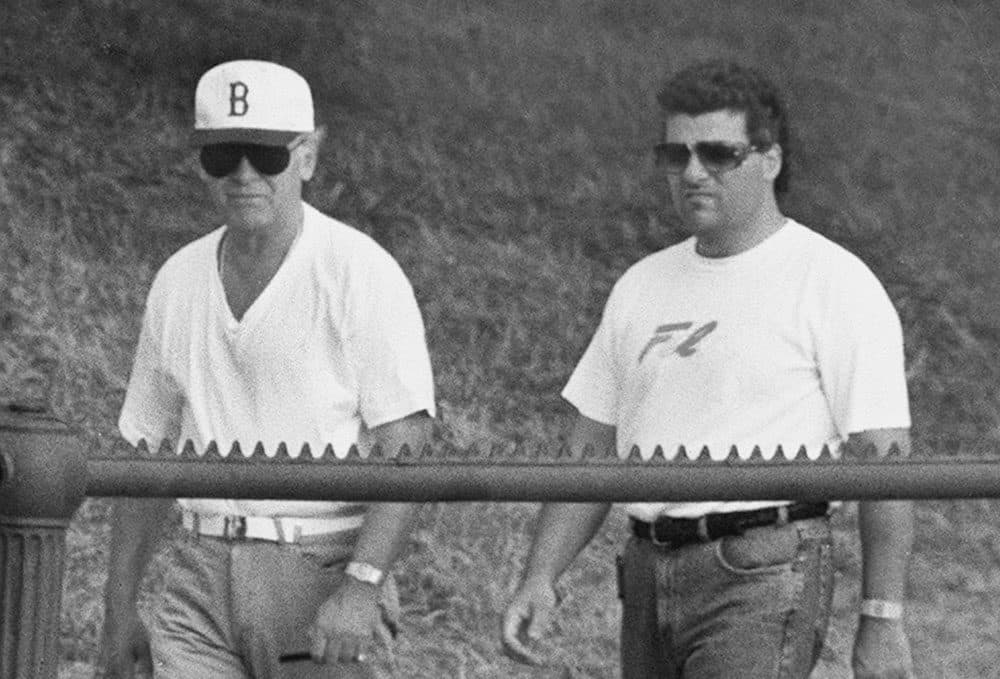

Bulger, 89, was killed Tuesday inside a West Virginia federal prison. While there had been nothing raised publicly about Bulger's involvement in the Gardner heist, it makes sense that his name comes up in speculative conversations about the audacious robbery. Considering his reach in the underworld at that time, Bulger could have known who pulled off the heist, if not where the artwork might have been stashed.

First, the vulnerability of the Gardner Museum to theft was an open secret in the criminal underworld. The FBI had briefed Gardner officials that two members of an East Boston crew associated with mob leader Frank Salemme had been plotting a robbery — and Bulger and Salemme often cooperated in criminal dealings together. Beyond that, Bulger was regarded as an IRA sympathizer and had met secretly in South Boston with the group's Belfast commander and signed on to an urgent request to support the cause. Stealing valued art to exchange it for guns and military supplies was long regarded as an IRA tactic for raising money. (Last year, art theft investigator Arthur Brand gained headlines by announcing that he had been told by two reliable sources that they had heard that the stolen Gardner paintings had wound up within the IRA.) Also, Bulger would have known that paintings by Rembrandt and Vermeer could be bargaining chips in case the criminal investigation against him in the late 1980s resulted in indictments.

To help his former boss, Connolly met with Bulger in early 1991. Connolly reminded him that there were true advantages for cooperating with the FBI — like the reward for the return of the artwork ($1 million at the time).

To Connolly's surprise, Bulger told him that he had already tried to gain information on the identity of the thieves and the whereabouts of the paintings. But not for the reasons Connolly had thought. He wanted to know who pulled off the theft because they had not sought permission from Bulger, or paid him the tribute Bulger believed he was owed.

Tribute? Under the cutthroat rules Bulger established, he had the right to a cut of all major crimes that were committed in his geographic area. This was not a theoretical tradition for Bulger. When bank robber Arthur "Bucky" Barrett refused to share the proceeds of a daring robbery he had pulled off during the Memorial Day weekend in 1980, Bulger hunted him down and killed him with a gunshot to the head in 1983.

Bulger went on to tell Connolly that he had sent out his close associates, Stephen Flemmi and Kevin Weeks, to see what they could learn about who was responsible for the theft.

Flemmi later confirmed to investigators assigned to the office of U.S. Attorney Michael Sullivan that Bulger had ordered him to find out who had pulled off the Gardner theft. Flemmi told the investigators in 2013 that, while he couldn’t provide him the answer, he did find out the artwork had been transported out of the country, possibly to Saudi Arabia, a day after the theft.

Weeks, according to a separate source, came back with an account that focused on a South Boston artist named John L. Sullivan Jr. who had been seen hanging around the museum in the days before the theft, and that parking tickets confirmed his presence there. But FBI agents disputed that possibility.

Connolly passed on the information that Bulger had provided him in several calls he made to his former FBI bosses in 1991. Perhaps because it never led anywhere, this was never mentioned in the mid-1990s when Connolly was prosecuted for racketeering and corruption in his dealings with Bulger. Nor was any mention made of the talks when Bulger was prosecuted in 2014 for a reign of terror, including more than a dozen murders, while he was an FBI informant.

While I was researching my book, "Master Thieves," I asked Bulger's defense attorney J.W. Carney Jr. if Bulger might have learned anything further involving the museum heist over the years. But Carney said that Bulger had never spoken to him about the Gardner, and that he doubted he had anything new to say.

Although he had written letters to friends and curiosity-seekers while behind bars, Bulger never mentioned any inside information that he might have had about the Gardner case. His death might finally end any speculation that such secrets will come out.