Advertisement

Cameras Pitched As On-Board Fishing Monitors

Resume

As the struggling New England groundfish industry takes up the cost of federally required, on-board fishing monitors, federal regulators are considering allowing 14 boats from Maine to Cape Cod to use cameras to record their catches instead. It's part of a pilot program to test out if cameras can replace humans and do it for less money.

Watching For When They Discard Fish

Located near fishing vessels moored in Portland's harbor, the Gulf of Maine Research Institute is a nonprofit that's trying to modernize the oversight of commercial fishing for cod, haddock and other groundfish.

In the "gear lab," Mark Hager demonstrates the equipment used to set up an electronic monitoring system: a computer, a GPS tracker, a hydraulic sensor and four weatherproof cameras.

"If you've ever been to McDonald's and you go to the drive-through and you pull up? They are actually using almost the same cameras we're using," Hager says.

Hager plays footage of an actual fishing trip from a vessel that's already been equipped with cameras. The captain and crew divide the haul into the adult groundfish they keep, and the juveniles they're required to put back into the ocean.

"They are going to go through quite a lot of sorting here," he says. "And those things he's putting in the basket are kept species. The real key, is — all this sorting is watched, but really what we're looking for is when they discard fish."

After the sorting, the captain places every single fish he's going to discard on a ruler so that the camera can see it — making a record of the fish and its length. Then he chucks it overboard.

"These are monkfish that he's throwing over, and then I need to put a length in," Hager says, as he watches the video. "I'm actually counting these bars to get 41 for the length in centimeters, and that comes out to an estimated weight of 2.47 pounds."

Back on land, a reviewer watches the video and gathers information about the species, length and weight of the discards. The reviewer's been trained by the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, which manages the fishery. NOAA uses the reviewer's data to develop and enforce the catch limits every fisherman must abide by.

The Problem With Human Monitors

To date, the data has been gathered by human monitors who go out to sea with the fishermen. Regulators and fishermen agree that there are serious problems with the current arrangement.

"It can be very chaotic, especially when you're a new monitor. It can be a lot to handle," Hager says.

Hager used to be an at-sea monitor.

"The captain and crew will get in there, they'll be dividing their catch up," he says. "Sometimes they'll help you out and throw the stuff they're going to discard into a separate tote, so that it's easier to get to. Other times they might just leave it all on the deck and then that's for you to sort."

It's also expensive.

NOAA estimates a monitor costs $710 per day at sea. The federal government has foot the bill since 2010, but this year, fishermen will have to bear the cost, which they see as financially unviable.

The hope for electronic monitoring is that cameras can vastly reduce the cost of labor, while collecting the same information as a human.

'With The Cameras, I Have Proof'

Randy Cushman fishes out of Port Clyde, Maine. He points out the cameras on his boat, a 41-year-old wooden trawler called Ella Christine. He tucks his hands into his slicker to keep them warm.

Cushman owns a small boat that he runs with only one crew member. Adding a federal monitor would get in the way, he says, which is why he's embraced the cameras.

"That third person is a huge hindrance," he says. "Everybody is tripping over each other and nobody is speaking to each other."

But after two years with cameras (he voluntarily has them), Cushman says he realized another benefit: The cameras validate the information he's reporting. In the future, he wants fishery scientists to use the data he reports to have a more complete picture of what's happening at sea.

"A lot of times we don't agree with what the science says," he says. "I want to believe what the science says, but I also want them to see what I'm seeing and a lot of times that doesn't happen. You know, they can say, 'The fishermen can say this or that. We don't know for sure, they may be just saying it.' With the cameras, I have proof."

The nonprofits administering the electronic monitoring program want to give captains the choice to use cameras, if it works for their business.

And that means it has to be more affordable than the current system.

Ecotrust Canada — the company that makes the equipment used in the program — says the initial cost for hardware and installation is between $6,000 and $8,000. But the cost of a reviewer can be as low as $300 a day.

If they prove to be cheaper, the regional administrator of NOAA says electronic monitoring could make it possible to observe more trips — instead of the just the fraction that are overseen by human monitors.

That's what Cushman wants. He believes cameras should be mandatory on all groundfish vessels, so that everyone has to fish better, and fish honestly.

"How do you keep track of every pound when nobody is on the boat?" he says. "You know, I want to think that majority of fishermen are honest at the end of the day and want it to work, to keep this sustainable for the next generation. But I feel as though there are still bad apples out there."

Cushman is a fourth generation Mainer. His father was a fishing captain out of Port Clyde; his brothers are lobstermen there, so is his son.

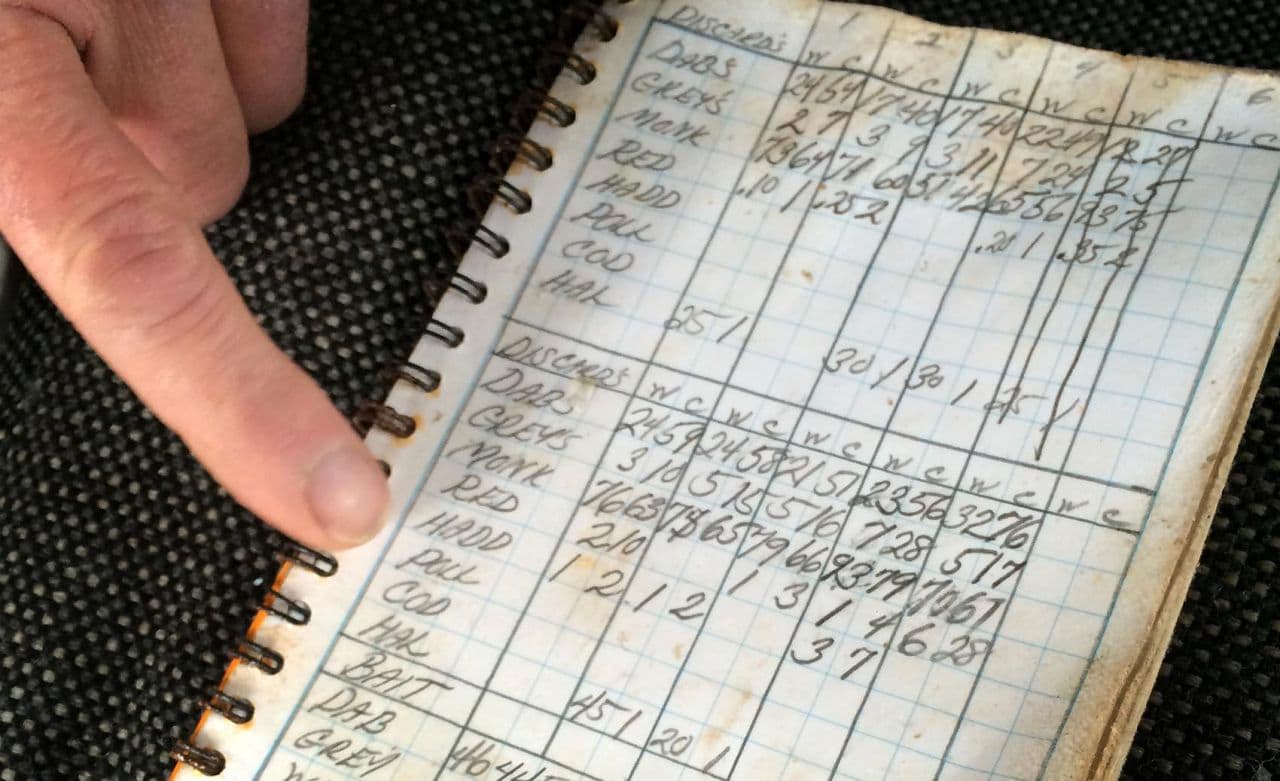

Cushman's been captaining for 34 years now. He's meticulously been writing down information about his hauls for years — in tiny waterproof notebooks. Even with the digital logbook, he says he'll still keep a record in his notebook this year.

This article was originally published on May 10, 2016.

This segment aired on May 10, 2016.