Advertisement

Questions Surround Prison Health Care As Complaints, Costs Rise

When medical tests at a Massachusetts correctional facility determined prisoner Steven Grubbs was diagnosed with chronic colitis in 2008, prison doctors might have prescribed Asacol, an anti-inflammatory drug that initially costs about $600 for a six-week therapeutic course.

Instead, doctors failed to tell Grubbs about his colitis until four months later, when his condition had worsened and would eventually require major abdominal surgery, according to medical records. While Grubbs endured weeks of literally gut-wrenching recuperation, taxpayers coughed up about $15,000 for his ileostomy surgery and are now on the hook for $600-a-month in MassHealth costs for Grubbs’ suppositories and colostomy bags.

“They saved $100 on a doctor visit and ended up spending thousands for surgery,” said Grubbs, 55, on parole from a five-year burglary sentence. “The damage is done; I have to live with this every day.”

At a time when Massachusetts is spending nearly $100 million a year on prisoner health care — nearly double the cost from 2001 — rising complaints about inadequate care are exposing taxpayers to even steeper long-term costs, an NECIR investigation has found. The costs include defending inmate lawsuits, paying for continued medical care and increased chances for re-incarceration.

Prisoners' Legal Services, the state’s leading advocacy group for inmates, now fields about 500 complaints a year related to health care — an increase of 67 percent from 2004. In that time, the state’s prison population has increased about 14 percent — from 9,872 to 11,629. (Another 14,000 short-term inmates are housed in county jails.)

“Like so much of public health, it’s pay now or pay later — and you’ll pay more later," said Joel Thompson, co-chair of the Heath Care Project at PLS, the Boston-based nonprofit.

Critics of the prison health care system attribute the rise in complaints to medical inflation and the privatization wave that has left 40 percent of the nation’s inmate medical in the hands of contractors.

UMass Correctional Health, a nonprofit arm of the University of Massachusetts Medical School, currently works under a five-year, per-diem contract signed in 2007. Prisoner advocates say that even nonprofits, forced to stay within the constraints of low-bid contracts, are susceptible to putting accounting before care.

“Some might say prisoners don’t deserve better because they’re being punished,” Thompson said. “But the punishment is loss of liberty, not loss of a limb, of eyesight, or of bowel function.”

Massachusetts Department of Correction spokeswoman Diane Wiffin said the state provides “constitutionally adequate medical care.”

Mark Shelton, a spokesman for UMass Medical School, voiced similar words. UMass Correctional has handled all or parts of medical care in the state’s 18 prisons since 1999. The firm does not handle jail.

“Given more than 11 years of services provided and the high-risk population and complex medical conditions we manage, we believe that UMass Correctional Health is providing care at the community standard,” Shelton said.

Both Wiffin and Shelton declined to discuss specific inmate cases, citing pending litigation and medical-record confidentiality.

II

Despite Massachusetts’ progressive stance on health care, the state’s prison system, according to complaints lodged with PLS and federal courts, repeatedly denies inmates adequate services as Massachusetts wrestles with an older and sicker inmate population and DOC budget cuts.

The complaints and lawsuits reveal dozens of instances in which medical service is alleged to have been flawed, delayed and, in one case, lethal. They show multiple cases of alleged failure or reluctance to test and diagnose inmates, seek outside consultation, or heed specialists’ directives. The alleged lapses have left some inmates with physical deformities and forced others, such as Grubbs, to endure pain and uncertainty. Grubbs has not sued the DOC.

“It’s managed care on steroids,” Thompson said. “There are binders filled with policies and procedures and protocols — all this lovely paper. Then there is what actually is happening on the ground, in the prisons, and it can be completely divorced from the paper reality.”

A Superior Court justice took issue with the prison medical system in a 2007 lawsuit filed against UMass Correctional Health by Abdullah Malik, who claimed he was denied proper treatment for hepatitis and a degenerative hip condition.

"Cost concerns have driven the privatization of prison medical care," Justice Peter Agnes Jr. wrote. "This court is mindful that state and local governments are struggling to find the resources to meet the most basic needs of the Commonwealth’s residents, particularly in the area of health care. However, bearing in mind that 95% of all persons who are incarcerated will be released and return to our communities, it is shortsighted (and indeed unlawful) to design public policies to address the health needs of persons living independently in the community, without simultaneously meeting the health needs of those who are incarcerated.”

In a 2010 research paper published in the Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, Thompson documented about 20 cases of alleged medical mistreatment. The paper included cases from county jails, where the state handles health care, not UMass Correctional.

Thompson, a staff attorney at PLS, outlined a broad array of alleged shortcomings that included medical providers trying to prescribe drugs to which inmates were allergic; disregarding information from inmates or outside specialists because of time and money burdens; and avoiding specialist consultations.

In addition, court records show that inmates have filed at least 30 federal lawsuits since 2006 against UMass Correctional Health and/or the Department of Correction. Of those 30 cases, 15 are pending, 14 were dismissed and one was settled. The cases include:

-- A 2010 lawsuit filed by Shirley Jay McGee, an inmate at NCCI-Gardner, which claimed he received substandard medical care for an injured shoulder and developed a hematoma. The case was dismissed on technical grounds.

-- A 2010 civil rights action by Humberto Feijoo, a prisoner at Bridgewater State Hospital, who has multiple sclerosis, relies on a wheelchair and claimed he was denied special footwear for his leg braces and other accommodations. The complaint is pending.

UMass Correctional has paid $101,750 to settle five inmate lawsuits since 1999, according to Shelton. The Department of Correction has settled five lawsuits for a total of $36,000 since 2005. Three of the DOC settlements involved wrongful death cases and two stemmed from inadequate medical care. The wrongful death cases settled for $5,000, $5,000 and $20,000.

The U.S. Supreme Court recognized in 1976 that quality medical care for prisoners is a civil right arising out of Eighth Amendment protections against cruel and unusual punishment. But the frequent dismissal of federal suits — and the small settlement numbers — point to a difficult road that inmates must travel when they enter federal courts.

Experts say courts are reluctant to side with inmates because evolving case law has raised the burden of proof to an almost insurmountable level: Inmates must prove that medical providers acted with "deliberate indifference’’ or “conscious disregard” of serious harm.

“The system is stacked against the inmates,” said Giovanna Shay, an associate professor of law at Western New England College School of Law in Springfield. “There are many serious cases raising really troubling issues and inmates are not getting relief, and that's unconscionable."

The 2007 Malik case before Justice Agnes Jr. offers a stark example. Agnes, after writing forcefully in support of quality prison health care and initially allowing Malik’s case to proceed, later reversed himself and dismissed the case on summary judgment.

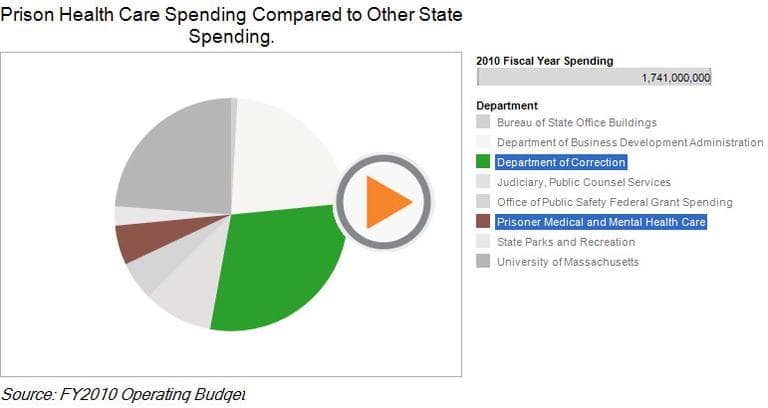

Massachusetts' spending on prison health care has mirrored the national trend, according to DOC figures. It now makes up 18 percent of the total prison budget, up from 6 percent in 2001. In fiscal year 2010, Massachusetts spent $514 million on prisons, with $94 million going to inmate medical care. In 2001 the numbers were $409 million and $53 million.

In addition, the Massachusetts DOC in the past two years has absorbed budget cuts of more than $30 million, or about 6 percent of total spending. The cuts have squeezed facility operations, health care and other services to inmates, prison advocates say. More cuts are coming, under Gov. Deval Patrick’s proposed budget.

One longtime Massachusetts prison doctor, who requested anonymity because he still works in the system, said budget constraints have led to tighter controls over medical testing.

“There’s an added level of screening to see if this MRI or some other procedure is really necessary," the physician said. “They have to do that now because they don’t have an extra penny to spend. They’ve added some new mechanisms for cost containment.”

UMass Medical School’s Shelton acknowledged that cost pressures have impacted the way screenings are handled but said quality has not suffered.

“Providing health care services in any form is a balance between access and cost,” Shelton said.

In the spring of 2006, when inmate Jasper Deeran developed severe back and abdomen pain, medical staff at MCI-Norfolk prescribed him ulcer medication, but refused for several weeks to order imaging or other tests, according to a medical malpractice lawsuit filed in Suffolk County Superior Court.

When Deeran’s belated tests finally came back that summer, they revealed an advanced cancerous tumor that claimed Deeran's life on Feb. 23, 2007, at age 52, according to the lawsuit. Deeran was serving a life sentence for a 1970 fatal shooting in East Boston.

Grubbs contends he’s a victim of care rationing. Grubbs was sent to Shattuck for a colonoscopy on Nov. 3, 2008, and returned that day to medium-security MCI-Shirley, where a prison doctor recommended a 30-day follow-up visit to Shattuck, medical records show.

Doctors at Shirley sent the request to a health care review committee at UMass Correctional Health, but Grubbs never heard back, the records show. Grubbs finally learned that he had been diagnosed with colitis when a bowel flareup landed him back in Shattuck on March 4, 2009, the records show. Doctors then altered Grubbs’ medications.

Experts say it’s difficult to pinpoint the true long-term cost of inadequate prison health care. But they say that unhealthy ex-cons are less likely to find housing and steady work; and more likely to use hospital emergency rooms and to transmit infectious diseases to the community.

"Success will depend on establishing a working connection between the prison medical system and the community medical system.”

Kamala Mallik-Kane, Urban Institute research associate

“People are coming out,” said Kamala Mallik-Kane, a research associate at the Justice Policy Center at the Urban Institute in Washington, D.C. “There’s a fiscal cost [to inadequate medical care] and there’s a public health impact as well.”

According to Mallik-Kane's research, virtually all reentering prisoners (8 in 10 men and 9 in 10 women) report chronic physical or mental health conditions that require treatment or management. Two-thirds of respondents reported active substance abuse within the six months prior to re-incarceration.

"One of things that surprised me is how pervasive prison health problems are," Mallik-Kane said. "Only half of the inmates in the states we studied even sought medical care in prison. Some said AIDS would make them a target. Others don’t want to call attention to themselves.

“There is a patient-education component to this. This is something you have to address with just about everyone involved. People cycling in and out of prison are part of the community. Success will depend on establishing a working connection between the prison medical system and the community medical system."

In recent years, Massachusetts lawmakers have sponsored bills that would elevate treatment standards for inmates, but the proposals have languished, according to Rep. Ruth Balser, D-Newton.

“It’s an important issue and I would like to see the Legislature take a more active role,” said Balser, a clinical psychologist. “It’s an issue that tends to fall into the background. But you’ll see greater sympathy when people understand there are people suffering in prison.”

Thompson said inmates need more avenues of recourse. He said internal medical grievance procedures are difficult for inmates to win, and court cases even harder.

“On the outside, there are people you can turn to for help,” he said. “Or you can change providers. You need accountability.”

With further DOC budget cuts likely, Grubbs worries there could be more inmates like him.

“Inmates don’t get the same medical treatment as patients outside of prison,” Grubbs said. “The prisons get away with it because they can.”

The New England Center for Investigative Reporting is a nonprofit investigative reporting newsroom based at Boston University. Lisa Chedekel and Tom Puleo are freelance writers for NECIR and staff writers at the Connecticut Health Investigative Team. This story started as a joint venture between C-HIT and NECIR.

This program aired on March 27, 2011. The audio for this program is not available.