Advertisement

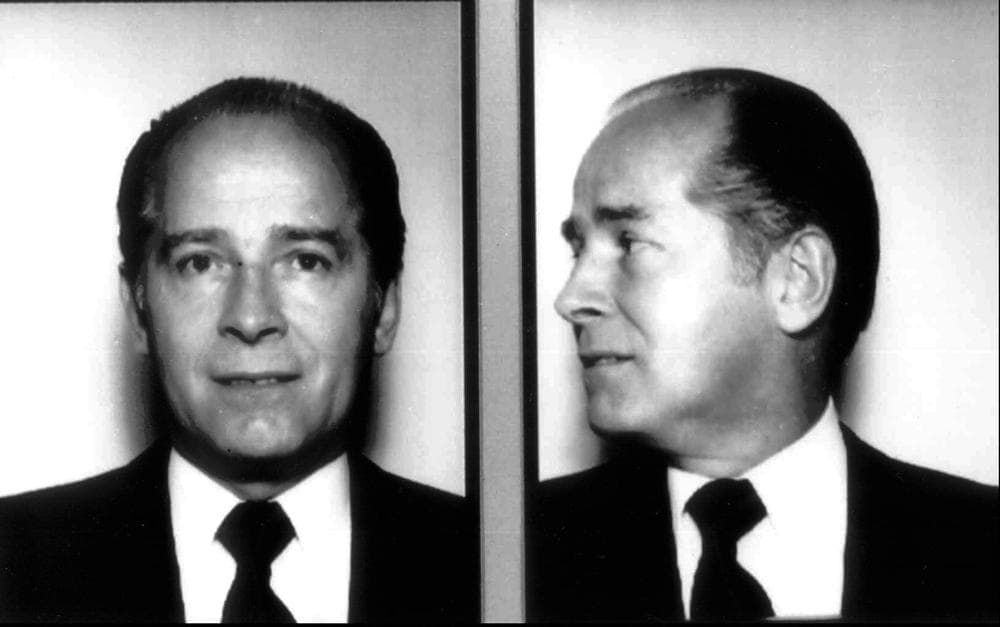

The FBI Agent Who Really Wanted 'Whitey'

Resume

When Bob Fitzpatrick was brought in as second-in-command of the Boston FBI office back in the early 1980s, it didn't take him long to figure out something wasn't right.

"It was almost immediate upon my arrival," he said.

It would be 20 more years before one of Fitzpatrick's agents, John Connolly, would be convicted of corruption stemming from his relationship with alleged Boston crime boss James "Whitey" Bulger, who was working as an FBI informant at the time. But for Fitzpatrick, it became appallingly clear the first time he went out to do an assessment on Bulger with Connolly and his supervisor, John Morris. Twenty years later, Morris, too, would confess to corruption.

Assessments were a common practice for checking up on informants and determining whether to keep them on or "close them." When Fitzpatrick spoke with WBUR this week, he recalled how his misgivings began on the car ride to Quincy to meet with Bulger.

Bob Fitzpatrick: What's interesting is, along the way, Morris keeps on saying how well I'm going to like this guy, that Bulger is a great guy. And so I get an hour's drive listening to how great he is and of course during the interview I develop the exact opposite opinion.

Deb Becker: Why? Why did you think that he was completely opposite of what Mr. Morris was telling you?

What immediately set me off was: most informants when you first meet them, they're great people. You know, they're actually here to help you. But when I met Bulger for the first time, he has a baseball cap over his eyes, he has dark sunglasses on, his arms are folded and he doesn't shake my hand. So I say to myself: 'OK, what did I do to this guy?'

So I get inside, and when I'm inside chatting with him it's very dark, I'm getting an impression that, you know, we're not seeing the light of day here.

Does he take off the sunglasses?

No, he leaves them on. He leaves the sunglasses on, leaves the hat on. But you know what? As I'm talking to him, actually interrogating him, on his right is John Connolly, which really upset me. Because first of all, Connolly shouldn't have been there and, of course, Morris was his supervisor and I was Morris' boss, so I immediately made a mental reservation that I'm going to grab Morris after this is over and find out what the heck is going on.

But anyway, during the interview, what I found is a guy who's bragging, a guy who's talking about how tough he is, he's talking about his Alcatraz experience, his Leavenworth experience — these are prisons, obviously, that are the most dangerous prisons in the United States — and basically what he's trying to impress me with is his braggadocio about how tough he is. He's an enforcer.

And of course that's not why I'm there. I'm there really to gauge how trustful he is in furnishing information and, more importantly, how reliable is the information that he's giving me — can I take it to the bank, can I use it in court? And my determination at the end of the day — at the end of the night, actually — was "no."

So if you suspected that Bulger was not telling the truth, was bragging, wasn't answering your questions, what did you try to do about it? Did you try to say, 'Hey look, this guy can't be an informant for us anymore?' And what happened?

When I got back in the car with Morris, in fact one of the first questions he asked was: 'Well, how did it go Bob?' And I looked at him and I said: 'I'm going to close this guy.' And Morris was silent, he was stunned. And what he actually said to me was, he said: 'No, you're not.'

I looked at him, this is my subordinate, and I was going to get into it with him and I said: 'No, I'm not going to do that.' And I really just shut up; we drove back in silence. So at the conference the next day, I made a formal, written recommendation that Bulger be closed and I wrote out a lot of the areas: distrust, furnishing false information, may be actually involved in drugs to this day, and so forth.

So then what happened?

He wasn't closed.

Why? If the bosses say 'close,' why doesn't it close?

It wasn't funny then and it's probably not funny now, but if I don't laugh, I get angry. Because, mistakenly, and again I think falsely, Bulger was propped up to be the guy who was going to take down the Italian Mob. Connolly and Morris produced memos saying that his information was spot-on, but you know during this whole period, even the United States attorney's office through O'Sullivan — Jerry O'Sullivan was the [organized crime] strike force chief — he put in a couple of memos saying that Bulger should be continued.

So I was fighting against the system and I lost. I think everything that he did, as the psychopathic person he is, everything he did was to gratify himself.

So do you think there was anything going on there in terms of what information he may have provided against Gerry Anguillo, who was the head of the New England Mafia at the time, that was information that would really just bolster Bulger's power in the Irish mob organizations?

Yes, I do. That's true. This was a war in some cases against the Irish guys and the Italian guys — Bulger representing the Irish guys and of course Anguillo representing the Italian guys.

And you can say that because your last name is Fitzpatrick.

Well, it's Foreign Born Irish, too — FBI. But you can also be Foreign Born Italian.

Let's talk about the murder of Brian Halloran. He was basically a hit man, is my understanding.

A leg breaker, yeah.

And he was an FBI informant and he gave agents information on a murder allegedly involving Bulger. Can you explain that case and what happened then?

We kept Halloran in a safe house and we chatted, we debriefed him, we started developing information. And I must say, you know, I was quite excited because this was confirmation against the guy I was trying to close. I mean, now I was getting real information that this guy is a murderer and he should be closed. And so I felt we had enough to present to O'Sullivan at the strike force to go after Bulger.

But in the interim, the information was leaked — I don't think it ever came out in court positively who leaked it, although I think Connolly was named — and Halloran, and unfortunately one of his friends, a fellow by the name of (Michael) Donahue, were machine-gunned and murdered. And this would go on, incidentally, I would have four of my informants killed in this way, and as it turned out, all by Bulger. And I fought again to close Bulger, but it was not closed.

You have a hard time saying that, even now.

I know. Listen, to this day, I find it very difficult to believe that any of our agents went bad. But I accept that they did go bad. And I'm grappling with that whole thing right now again, as I have been for the last 15 years, in trying to make some sense out of what actually happened. You know, I never expected that from my bureau, from the FBI. But Boston unfortunately had a problem, and it was a serious problem, and I don't believe the whole truth has come out even yet.

Fitzpatrick says he was increasingly marginalized for his efforts to blow the whistle on corruption within the FBI. He left the bureau in 1986. He has since testified on multiple occasions about his experience during his time in the Boston office. He says now, with the arrest of "Whitey" Bulger, the alleged crime boss could name more people within the FBI — both past and present — who have not been charged with corruption but who played a role in keeping him out of prison all these years.

This program aired on July 7, 2011.