Advertisement

'Whitey' The Prisoner: A Master Manipulator

ResumeSecond in a two-part series

When prosecutors set 19 murders before the jurors at James "Whitey" Bulger’s coming trial, they will be going back some 40 years. But newly obtained FBI and prison records take us back almost 60 years.

The records show that Bulger began informing against his criminal associates far earlier than previously thought. There are other surprises too, including the young Whitey's blue chip political connections and how they may have helped him in prison.

Prison Letters Reveal A Different Side Of Bulger

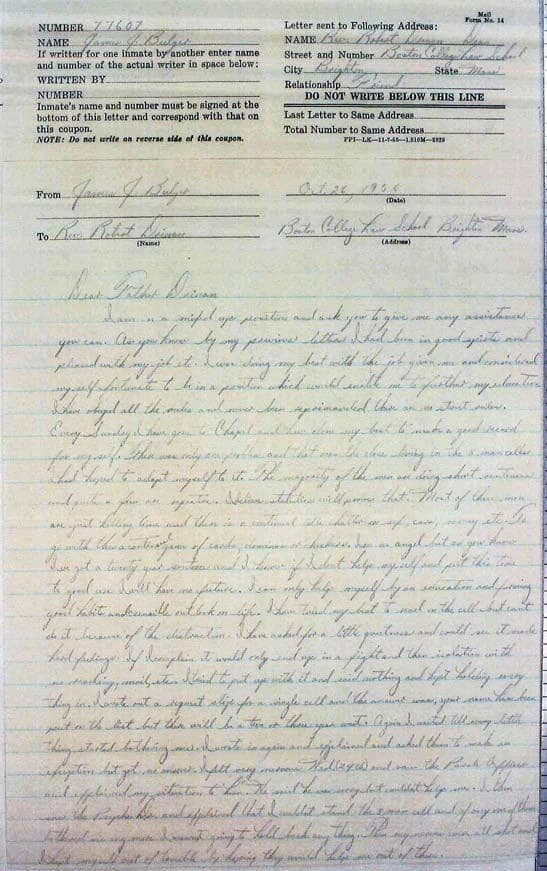

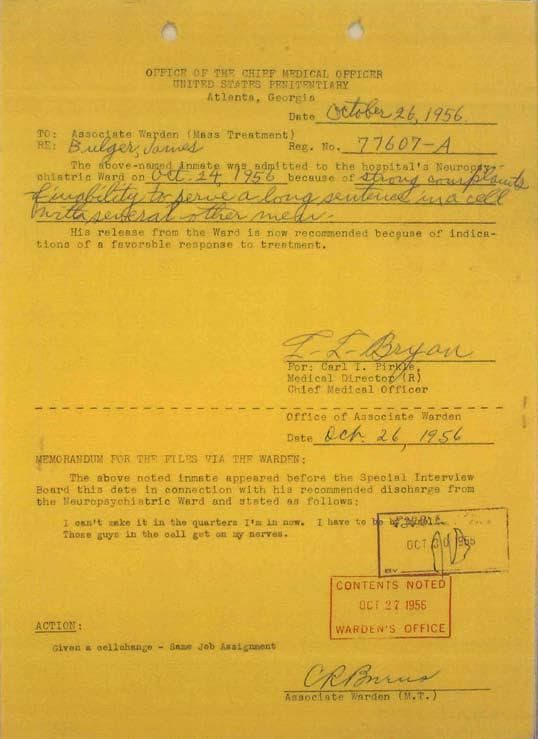

BOSTON — Convicted bank robber James "Whitey" Bulger entered the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary in July 1956. By the end of October he was in the psychiatric ward. He addressed a letter back to Boston. The message was simple: Get me outta here:

I then saw the Psych Dr. and explained that I couldn’t stand the 8-man cell and if only one of them bothered me any more I wasn’t going to hold back anything. Then my nerves were all shot and I kept myself out of trouble by hoping they would help me out of there.

Writer Dick Lehr, who obtained a copy of the letter along with other prison files and documents that have never been reported before, is writing a biography of Bulger with his fellow former Boston Globe reporter Gerry O'Neill.

“He was put in an eight-man cell and it's driving him crazy,” Lehr said. “This is a man, then and now, who was a control freak who liked to be able to control his environment.”

An excerpt from the letter underlines the point:

I have asked for a little quietness and could see it made for hard feelings. If I complain it would only end up in a fight... I tried to put up with it and said nothing and kept holding everything in... till every little thing started bothering me.

A prison newbie complaining he can’t take it anymore. On the ladder of tough guys, there's no rung lower than that. Compared to the mythic "Whitey," this version makes a poor match. Yet in that first intake photo of the 26-year inmate at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary, you can see the trace of fear and vulnerability.

“It's really a cry for help; it's a call for help,” Lehr said.

And Bulger is reaching high above his own family back on Logan Way in Southie to get it. He is writing it to an influential priest at Boston College.

The letter continues:

Would you please see if I have any legal right to a Penit. transfer, any legal rights at all. This is my first time in any prison. Please explain to my brother Bill for me and in turn he can explain to the family and my girl.

I show a copy of the letter to Kevin Weeks, the right-hand man who got left out on the secret his boss was an FBI informant. Though he still feels betrayed, Weeks holds Bulger in a certain awe.

“He's very manipulative," Weeks said. "He's very Machiavellian. Everything he writes or says or does is to his advantage.”

Weeks sees the letter as the work of a master. He points to the passage where Bulger tries to win the priest's sympathy by attacking the inmates' vices:

Most of these men are just killing time and there is a continual idle chatter on sex, cars, money etc. To go with this is a continual game of cards, dominoes or checkers.

“It's almost as if some young altar boy has been kidnapped and dumped into a federal penitentiary and it's, ‘Oh my gosh, what a terrible situation to be in,’ ” Lehr said.

In a proclamation of his own piety, Bulger writes to the priest, "Every Sunday I have gone to Chapel and have done my best to make a good record for myself.”

Then comes what Lehr calls the key line:

I am no angel, but... I know if I don't help myself and put this to good use I will have no future.

Therein starts the theme of Whitey as “the good-bad guy,” Lehr said. “And it’s picked up through the decades so that Whitey Bulger, in the myth of South Boston as it plays out in the '50s, '60s, '70s, '80s and '90s, he is the good-bad guy.”

As opposed to the bad-bad guys.

Bulger’s letter never got to its intended recipient. The prison disapproved of its contents, so the letter was consigned to the prison’s central files. Otherwise, we wouldn’t know about it. And we wouldn’t know that it was addressed to Father Robert Drinan, dean of the Boston College Law School and future congressman of international reputation.

Father Robert Drinan's Bulger Association

It’s a name that jumps off the page of Whitey’s federal prison records. But it’s only the first one that jumps off the page; an even bigger name would follow.

When Bulger put Drinan on his list of correspondents as a "close" friend, the Bureau of Prisons asked Boston Police to do a background check. And the Boston Police replied that Drinan indicated he had known the family for a long time and would be happy to correspond with Bulger.

How in the world would Drinan be connected to the "habitual criminal?" Most likely through a certain Boston College undergraduate, who may have been one of Drinan’s favorite students. The student was William Bulger, Whitey’s younger brother, and he would soon attend BC's Law School, where Drinan was dean.

“The inference is that it's through Bill Bulger there's established a beachhead with Robert Drinan,” Lehr said.

From early on in Whitey's prison term, Father Drinan was listed as the person who would be Bulger's parole adviser upon his release. The only correspondence Lehr has seen is the one letter the prison held onto.

Father Drinan died in 2007. His papers and a recent Drinan biography contain no reference to either of the Bulger brothers. And when I talked to Drinan’s former congressional aides, his former chief of staff and his closest political advisers, they were stunned at the link to Whitey.

A typical response came from Jerome Grossman, who became one of Drinan's best friends after recruiting him to run for Congress as a progressive, anti-war candidate in 1970.

“It's a complete surprise,” Grossman said.

Then again, those who knew Drinan say the priest kept his priestly duties and corporal acts of mercy — like visiting or writing to prisoners — a private matter and apart from public duties.

The letter to Drinan closes with the tone of an order being directed to a future subordinate:

Well, Father Drinan, that’s about it and it’s the true story seen through my eyes... Write me as soon as possible. James J. Bulger 77607

Seeing the same letter, former Boston Police Detective Eddie Walsh smiled. The 90-year-old figures he’s seen just about everything. He first saw Bulger in 1955.

“Bulger’s very devious and would try anything he could do to get out of there, you know,” and reach as high as he could to do it, Walsh said.

I ask him about Whitey checking into the psychiatric ward.

“What’s this tell you?” I asked Walsh about Bulger’s nervous breakdown letter.

“It tells you he’s full of baloney,” Walsh replied.

Blue Chip Connections

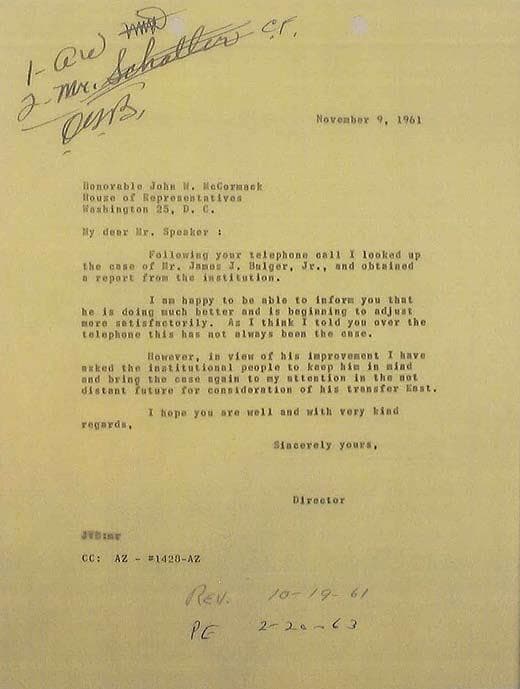

Father Drinan wasn’t Bulger’s biggest blue chip connection. You want to know how big that connection was? His biggest blue chip swore in Vice President Hubert Humphrey in 1964.

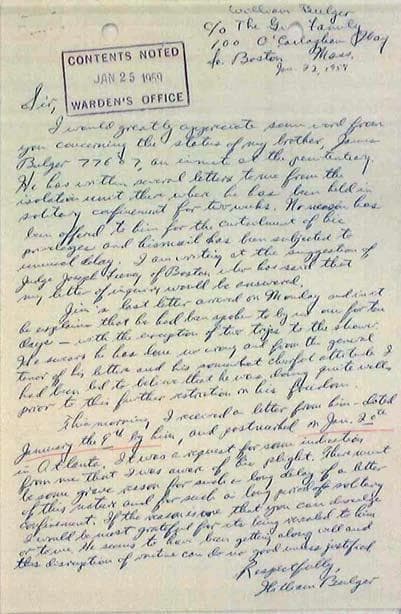

By 1964, and before Whitey’s third attempt to win early parole from a 20-year prison sentence, John McCormack was speaker of the U.S. House. In a totally implausible and fortuitous electoral coincidence, McCormack happened to be the congressman for South Boston and a neighbor of the Bulger family. For the Bulgers, this gave new meaning to "luck of the Irish."

“They are fortunate to have access to John McCormack, who has easy access to the director of the entire Federal Prison System,” Lehr said.

In 1956, the year Bulger first went to prison, McCormack was still House majority leader, No. 2 in the line of succession, when young college student William Bulger, on behalf of his family, asked the congressman for help. To the normal congressman it would have fallen into the normal everyday requests for constituent services. Except McCormack wasn't your normal congressman, as Lehr pointed out.

“He's got the director of the Bureau of Prisons practically jumping up and down to check on James 'Whitey' Bulger's status in prison,” Lehr said.

The letters from the Bureau of Prisons to McCormack are cordial and they come quickly. But they also explain diplomatically that McCormack’s constituent is a bad ass.

“I regret that I have to report that he has had some difficulty at Atlanta,” wrote the director to McCormack in February 1959.

The so-called "difficulty" was an attempted prison escape. In fact, Bulger's conduct at the Atlanta Penitentiary got him sent to the notorious prison on a rock, Alcatraz. And no prisoner qualifies for early parole out of Alcatraz.

For Bulger, the payoff from his connection to McCormack would be down the road, Lehr said, but “what gets established is John McCormack has an interest in this inmate.”

There's no suggestion or any evidence at all of any arm-twisting by McCormack. He's simply doing constituent services for the Bulger family in his own hometown. But how many inmates hold the interest of a congressman who presides over the House of Representatives?

After an inquiry from McCormack in 1961, the director of the Bureau of Prisons wrote the warden of Alcatraz asking when he thought Bulger would be considered for transfer.

"My dear Mr. Speaker,” the Bureau of Prisons director wrote back to McCormack. "I have asked the institutional people to keep him [Bulger] in mind and bring the case again to my attention in the not-distant future."

John F. Kennedy was president when Bulger was moved out of Alcatraz to the penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kan., and then applied for early parole in 1963. Bulger was denied, but he was transferred closer to home to the penitentiary in Lewisburg, Pa. Then in March 1965, Bulger won early parole on his third attempt. He had served only nine years of a 20-year sentence for three armed bank robberies. Prison officials gave him $10 and opened the outer gate.

As for Whitey's post-prison adjustment, Kevin Weeks might be considered an authority.

“Do you have reason to believe there might have been more bank robberies?” I asked him.

“Oh yeah,” Weeks responded. “Bulger claimed to have committed 19 bank robberies after he got out of prison.”

Before Whitey left prison, officials had decided he would not have to visit a parole adviser as a condition of release. That meant Drinan, who was named Bulger's parole adviser at the start, was spared the assignment and, as it turns out, any future embarrassment. Otherwise, the heroic priest and progressive celebrated for the honor of being named to President Nixon's "enemies list" might have had the dishonor of being named to Bulger's "friends list."

In part 1 of this two-part series, we reported on newly uncovered documents that show Bulger started snitching on fellow criminals back in the 1950s, and that his life on the run with a South Boston girlfriend back then began a pattern he would follow for decades.

This program aired on May 30, 2012.