Advertisement

REVIEWS

Huntington Makes 'Invisible Man' Visible

It’s evident from the first minutes of “Invisible Man” at the Huntington Theatre Company that we are in the presence of nobility. The nobility of a classic American novel and a seminal work on African-American history. It’s also immediately apparent that we’re in the presence of a beautifully designed play that is going to treat Ralph Ellison’s work with utter respect.

Whether we are in the presence of a great theatrical event is another matter. Novels, by their very nature, take us out of our time and place. The difference in prose style between then and now forces us into accepting a different dialectic, and concentrating on the page keeps contemporary life at the corners. A play needs to work harder to make the past palpable and as hard as this production works, it feels more like a historical icon rather than a deeply moving or insightful about the world we live in.

The protagonist from the 1953 novel is an unnamed black man living freely in a New York apartment because no one can see him – i.e. no one he meets accepts his humanity; his blackness makes him a Rorschach Test rather than a man. He has been juked and mistreated by almost everyone in his life, from white racists and Communist Party members to black nationalists and the presidents of a black university. None of them can see him for who he is, making him invisible, but he can’t really figure out who he is. Richard Wright meets Franz Kafka.

He is victimized by mostly stick figures – the Southern racist, the powerless black university administrator, the heartless Communist, the do-gooder liberal, the woman with jungle fever.

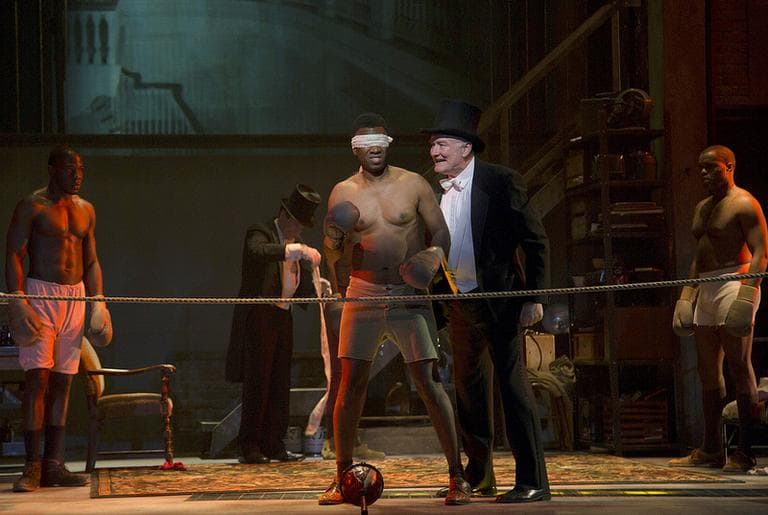

We meet him on the Huntington mainstage (through Feb. 3) sitting in a T-shirt, having retreated from a life of ambition. Flashbacks tell us why. Early on he’s forced to fight blindfolded against other young, black men and then he’s expelled from university by a fascistic black college president who merely wants to show that he can exercise power in his small world.

All of this is gorgeously staged. Characters retreat to the sides like hellhounds on his trail. The stage is exposed, but it never feels bare. Props are used sparingly, but always thoughtfully. Every element of the design dramatically advances the story. (Full disclosure: The projection design was done by Alex Koch, the son of friends of mine.) Christopher McElroen directs an excellent cast, particularly Brian D. Coats and a couple of local favorites, Johnny Lee Davenport and Jeremiah Kissel. Teagle F. Bougere in the title role is terrific in the parts that call for great oratory, not so wonderful in the parts that call for naivete. But then naïfs are generally a thankless role. Pippin and Candide are probably the least interesting characters in “Pippin” and “Candide.”

And you couldn’t ask for a more respectful adaptation than Oren Jacoby’s – more than respectful, really, since the three hours never drag.

So why does it feel like an artifact? For one thing, I couldn’t quite get past the fact that a man not unlike the Invisible Man has just been re-elected president of the United States. Some, notably David Samuels, have used this as ammunition against President Obama, that he’s a blank slate waiting to be filled by others’ expectations. Or that it speaks to a universal condition of invisibility – no one sees anyone for who they really are and we all have difficulty escaping from other people’s identities.

Here's how the writer, director and star describe it:

Perhaps. But this is still a play about a black man victimized by characters living in a white man’s world. Granted, race is still an enormous issue, but the election proved that anyone who thinks this is still a white man’s world does so at his peril. Just ask Mitt Romney.

Enough about politics. Dramatically, "Invisible Man," which began life in Chicago and hopes to go to New York, is victimized by mostly stick figures – the Southern racist, the powerless black university administrator, the heartless Communist, the do-gooder liberal who literally can’t recognize the Invisible Man, the lefty woman with jungle fever. Ellison fills these characters out more fully on the page than they can be onstage, though his clashes with the black characters played by Coats feel more real.

I’m certainly not arguing with the play as a history lesson or with any of the sensational stagecraft. Whatever problems I have with it, “Invisible Man” is a pleasure to watch – aside from the Invisible Man’s miseries and the reminders of this country’s tortured history. But this epic journey ultimately doesn’t have the power of more considered and focused work for the stage, such as Lorrainne Hansberry’s “A Raisin in the Sun” or August Wilson’s “The Piano Lesson.” By that gold standard, “Invisible Man” gets the bronze.

This program aired on January 11, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.