Advertisement

Free Health Clinics For Uninsured Thrive In Mass.

ResumeMassachusetts has the highest rate of residents with health insurance in the country, but that still leaves about 277,000 men, women and children (PDF) who aren't sure where to turn when they get sick and often put off care because it costs too much.

A loose-knit network of free clinics in churches, synagogues and vacant offices around the state — often run by retired doctors and nurses — is quietly caring for many of these patients.

Beth El Becomes A Clinic

"The flu season this year is really bad, and there are flu shots available. Who's interested?" asks Julia Koehler, in Portuguese and English, as she glances from one weary or pale face to another. Twenty-one men, women and children sink into folding chairs in a hallway at Congregation Beth El in Sudbury. On this night, the hallway lined with folding chairs has become a makeshift waiting room.

Free flu shots are a bonus on this night for patients who’ve come in with a sprained back, dizziness or a feeling that their diabetes is getting worse.

"Now, have you lost any weight?" Dr. Dick Wolk asks as he waits for an interpreter to translate his question into Portuguese.

"No," his patient says sheepishly.

Wolk wags a long finger at the admittedly overweight woman he's brought to his "office" — a card table behind a striped cloth folding screen. Wolk's patient wants to know if she's taking the right pills to control her diabetes.

"We can give you all the pills in the world, but only you can lose weight. It’s up to you," he says. "There is only so much medicine can do." The patient promises Wolk she’ll pay more attention to calories and get more exercise.

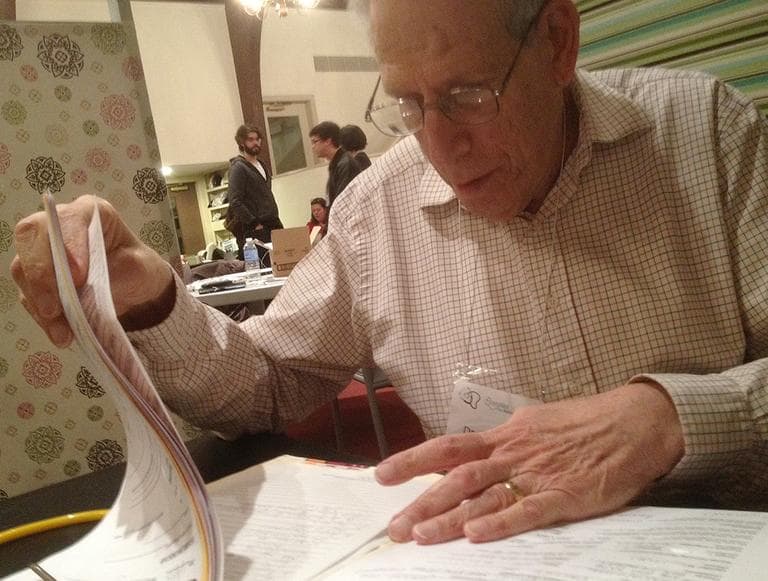

Wolk is one of seven to nine physicians (most are retired) who spend their Tuesday evenings treating patients at what’s become known as the MetroWest Free Medical Program, in the temple sanctuary.

"All of the chairs (in churches it would be pews) have been removed by a volunteer crew that came in in the late afternoon," Wolk says, gesturing across the room. "On the one end is pharmacy education," where students from the Massachusetts College of Pharmacy check and write prescriptions.

A local Stop & Shop stores medicines for the clinic, at no charge. The Massachusetts Medical Society cover the doctors’ liability insurance and MetroWest Medical Center provides free lab work and X-rays. There’s a crew of nurses, interpreters, social workers and a physical therapist — about 35 volunteers on any given clinic night.

"At the other end of the room, you have a table with a nutritionist," says Wolk, continuing his visual tour. "Above her, on an elevated platform that is usually used for services, we have a social services team that helps patients apply for food stamps, heating assistance and health insurance."

Nurse Pam McGrath updates patient files at a table near the entrance. "I feel very strongly about paying forward," says McGrath, who started volunteering at the clinic three years ago, shortly after her daughter survived a serious car accident.

"She should not have lived," McGrath says. "So when I was taking care of her, and we realized that it was going to be OK, I got online and was looking for a program to volunteer with and I found this one."

Now McGrath is paid, one of three part-timers. The clinic raises about $150,000 a year for employees and supplies. McGrath’s job is to make sure patients follow the doctor’s orders.

"Things that we would normally take for granted you can’t take for granted anymore," she says. "You know, take it with milk. Can you afford milk three times a day, is that something your family can do?" If they can't, McGrath makes sure the patient has milk.

Despite Mass. Law, 'Still A Huge Need'

MetroWest Free Medical Program treats up to 60 patients a night and logs about 1,800 visits a year. Men and women come from 20-30 miles away. Many of these patients could receive good care at one of the dozens of community health centers or hospitals in Massachusetts, but some say those institutions are intimidating.

In the almost nine years since this clinic opened, there are fewer patients with a sprain or the flu and more with chronic conditions: diabetes, high blood pressure and mental health problems. Mason, from Quincy, stopped in on this night for a mental health consult.

"You’re always worried when you go and talk to a psychiatrist," he says, "whether or not they’re actually going to listen to you and help you without prejudice and he definitely did. The quality of care here is as good as any paid clinic."

Mason, who lost his student health insurance because he’s transferring schools, says there are too many gaps in health coverage, even in Massachusetts.

"I suppose if we were in Alabama or Kentucky or something, this place would probably be packed to the gills," he says, "but I believe a lot of people here are first- or second-generation immigrants, which I think predisposes them to needing this kind of place."

Doctors and nurses at this clinic don’t ask patients about their immigration status. We agreed to use just Mason's first name because Dr. Wolk and other organizers don't want patients to worry that the clinic will reveal their identity.

The Affordable Care Act is supposed to provide insurance and a consistent doctor for many patients who currently rely on the roughly 1,200 free clinics around the country. But even after the federal law is operating in full force, there may be as many as 26 million people who will still need free care (PDF). The lesson from Massachusetts, where a health coverage law has been in effect for five-and-a-half years, is, plan to stay open.

"There’s still a huge need for programs like ours," says MetroWest director Kim Prendergast. "There’s a lot of people still losing jobs and losing insurance and it’s a confusing process. We also see that health insurance doesn’t mean that you have access to care and there’s a big shortage of primary care doctors in Massachusetts and that’s true around the country."

Prendergast looks off to her left where the clean-up team packs clinic supplies into big plastic tubs that will be stored in a shed at the back of the synagogue. Then, most Tuesdays, a set-up crew repeats the weekly transformation from house of worship to house of care and hangs a white canvas sign over the main entrance, "Walk-ins Welcome."

This program aired on January 22, 2013.