Advertisement

At 50, Bread And Puppet Still Challenges Business As Usual In Theater And America

“It’s not an antiwar piece,” Peter Schumann, founder of Bread and Puppet Theater, explained of the troupe’s opening performance at the Boston Center for the Arts Thursday night. “It’s an anti-American culture piece. And it’s an anti-noise piece. And it’s an anti-modern culture piece.”

In this introduction, Schumann listed the enduringly challenging themes of the Vermont-based experimental, political mask and puppet theater as it arrives in town at the start of the company’s 50th year.

For their annual Boston run, they’re offering a double bill at 7 each night through Jan. 27. The evening opens with a breathtaking fable, that “anti-modern culture piece,” Dead Man Rises. It’s a revival from 1967, when the company performed it for “students who occupied Columbia University in protest of Columbia University’s indirect participation in the war in Vietnam,” Schumann said.

It’s followed by a new companion piece, The Possibilitarians, an epic and raucous pageant addressing 17th century English radicals called the Diggers who planted parsnips, carrots and beans on common land as they sought to found a society of greater equality and without private land ownership. This was much to the displeasure of local manor lords, who harassed them and defeated them through courts and by force within a few years

“Quite meaningful even though not many concrete results come of it,” Schumann told the audience. But here the theater mulls parallels to the Occupy Wall Street movement, looking backward to consider ways to challenge inequity now.

(Bread and Puppet also performs their “family-friendly” Circus of the Possibilitarians at the Boston Center for the Arts at 2 p.m. Jan. 26 and 27.)

Bread and Puppet began as one of the landmark New York experimental theaters of the 1960s, identified by their trademark giant papier-mâché puppets and their tradition of distributing fresh baked bread free to audiences at the end of performances. But dance was at the center of their work. The company was founded in 1963 by Schumann, a German immigrant who witnessed the destruction of World War II as a boy and then immigrated to New York, where he studied in the same John Cage-influenced dance workshops that spawned the avant-garde “pedestrian” styles of the Judson Dance Theater.

Bread and Puppet made their name with theatrical spectacles and street protests against poor housing conditions, the Vietnam War, nuclear weapons (Schumann organized thousands to lead the June 12, 1982, Disarmament Parade in New York City), and the United States’ involvement with torturous regimes in the Americas. The company vividly merged radical ‘60s theater with the alchemy and magic of traditional ritual, public pageantry and folk art.

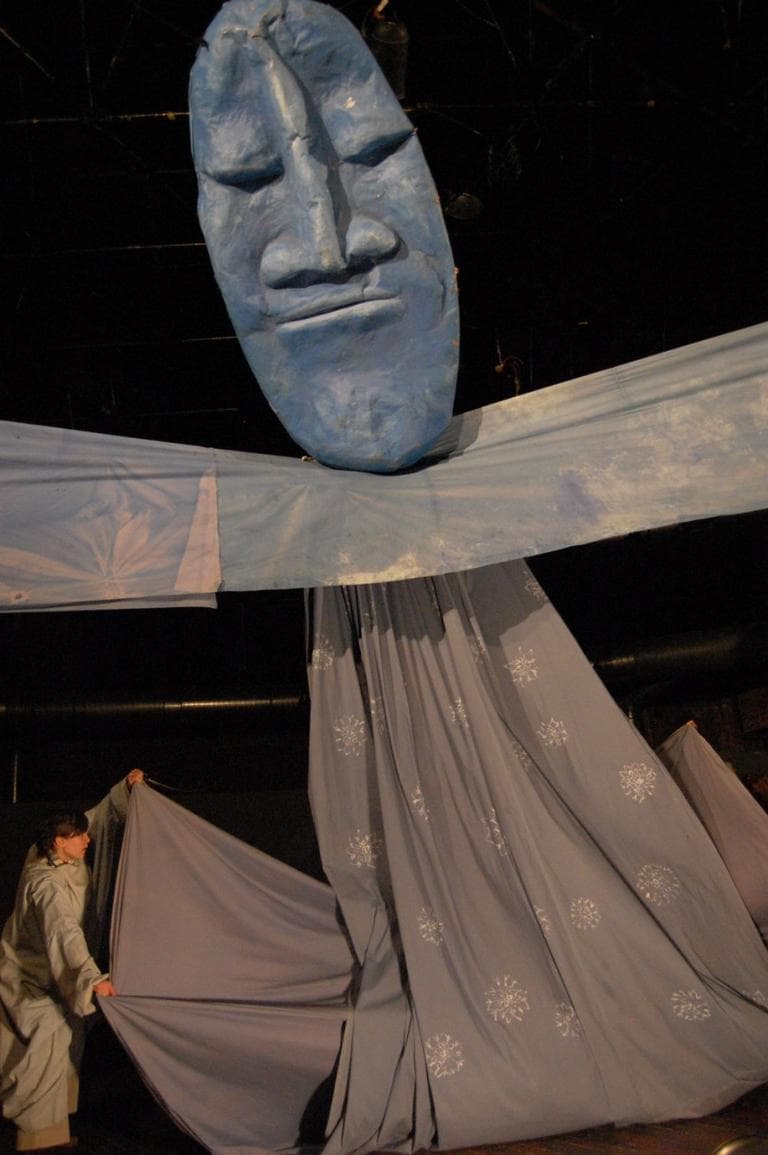

Dead Man Rises begins with low slow subdued horns sounding as a single footlight illuminates the set, a gray landscape painted on three curtains. A tall masked figure, a woman, dressed all in white, slowly, carefully walks along the stage—a sort of dance inspired by traditional Japanese Noh dance theater. She arrives at her destination the River, which turns out to be personified by an even taller white-faced figure in a black robe. She kneels and seems to lick the River’s feet to drink. A stagehand, hooded and clad all in black, like an assistant from Japanese Bunraku-style puppetry, removes the woman's sandals. She walks closely behind the River, until another figure with white face and black robe collapses onto the center of the stage.

“There is a dead man laying in the river,” a woman’s voice whispers in the dark at the right. “What will you do with the dead man?” a man whispers from the darkness at the left. Woman: “I will put the dead man on the back of the river and take him to my house.” The white figure picks up the Dead Man, and walks “home” with him between her and the River. Then she lays with him in her “bed,” just a pillow set on the stage. Night comes as a black fabric that covers them, and departs as Morning, a white faced figure in black robe that rises from them.

“Dead Man, I will open your eye,” the woman’s voice whispers. A bell sounds. The white figure rises. The Dead Man rises. More chimes. The Dead Man and the white figure stand, rocking left and right, exiting to the right. The River returns, finds the woman’s sandals, has them tied to its back by the stagehand and strolls off.

It’s a curious series of events, stripped to bare elements, but freighted with importance. The white figure is a Good Samaritan who revives the Dead Man through sheer human tenderness. In the middle of the action, her extraordinary decision seems natural, but her motivations are unexplained. Why take care of this Dead Man? The performance feels like a haiku. There is magic in the slow and delicate pacing, the rich somber horns, the way the river, the night, the day slowly, tenderly move. It’s breathtaking.

Bread and Puppet moved to northern Vermont in 1970, where it produced "Our Domestic Resurrection Circus," a two-day outdoor festival of serious puppet shows, satirical circuses, and poetic pageants featuring casts of hundreds annually through 1998. Attendance each year grew to as much as 30,000. The theater’s history is told in the troupe’s barn museum (free admission), filled with tableaus of cardboard and papier-mâché characters, in Glover, Vermont. Holland Cotter of the New York Times has called it “One of the great sights of American art."

Schumann has long been an advocate of “Cheap Art”: “People have been thinking too long that art is a privilege of the museums and the rich. … Art is food. You can’t eat it but it feeds you. Art has to be cheap and available to everybody.” His shows have a different feel from traditional theater—often performed in more rough-and-ready venues at lower cost.

“His work—moral theatre—is a major statement from the Left and presents the interest of an effort to carry on a large enterprise outside of the money economy,” Stefan Brecht wrote in his two-volume 1988 history The Bread and Puppet Theatre.

Schumann’s economic critique drives the evening’s new performance, The Possibilitarians. It begins with a Greek chorus of nearly 40 performers standing flanking a flipbook of banners painted with expressionist renderings of struggling people.

“In 1649 on April Fools Day, the Diggers and Levelers started their rebellion,” a narrator shouts as the chorus sings an old Christian shape note hymn. “We come to plant grain on the common which belongs to us in the first place! Private property is arrogant and stupid! Nobody has the right to sell the earth!”

The following acts are a creation myth. A crew in blue gowns pulls ropes over squeaky pulleys to fly a giant Sky puppet into the air. It has a blue papier-mâché head as tall as a person, papier-mâché hands, and a body and arms made of flowing blue fabric. It soars from the back of the stage out over the audience, where the awesome up close appearance of this puppet spirit provokes gasps from the crowd.

The Sky births and cradles dancing (cardboard) clouds. It births a pile of giant, mud brown body parts—arms and legs and torso and head which stand up and squabble over their purpose and who’s in charge. “Because all the parts of the body were constantly at war with each other,” a narrator says, “they could not see the paradise which opened its door for them.”

A yellow door appears behind the body parts and out steps a woman in a black, sequined dress and a rhinoceros head. She smokes and drinks and burps, a parody of elegance, then exits.

The arms, legs, torso and head finally form up into a giant mud brown reclining woman, who births a baby from her side. These puppets are giant, rough totems that seem to come alive, to breathe. The performers lay the body down at the front of the stage and exit.

After this astonishing beginning, the play shifts to a satirical, didactic mode. A crowd of flat cardboard people—a grotesque caricature of a squawking community—offers the baby help. They proclaim the philosophy of the Diggers: equality, the need to rectify people’s alienation from each other and the land. “We have a right to the common ground both by the law of the land and by reason,” one of the cardboard people shouts as she leads the group in digging with a shovel. “And therefore we have begun to bestow our righteous labor upon it."

The next act is a mock lesson on “the three basic skills of hands and feet.” It’s played for laughs, but with a serious point behind them. A teacher speaking French and a second woman translating the talk into English explain how to caress, embrace, walk, dig in the dirt, “raise your hands against the existing order of life.”

“The third skill of feet is kicking the ass of government,” they conclude. A giant puppet depicting a political boss in a top hat and waving a cigar enters. The teachers turn it around and lift up its coattails to reveal a goofy pink butt. The crowd kicks it over and then disarms a riot cop who runs in in response.

These middle scenes run too long—we get their point pretty quickly, then the clowning and lessons grow tedious. And their tone feels off. Does Schumann really mean to portray the Diggers as a slobbering moron mob?

In the final scene, dramatically lit by a single footlight, performers in suits and ties wage a fight to the death—“the eternal battle of good and evil,” Schumann announces—armed with wooden swords, axes and sledgehammers. The heavy-handedness of this description is mitigated by the delicacy of the performers’ violent, slow motion dance as a chorus sings a Christian hymn. Finally all lay down dead and all goes quiet.

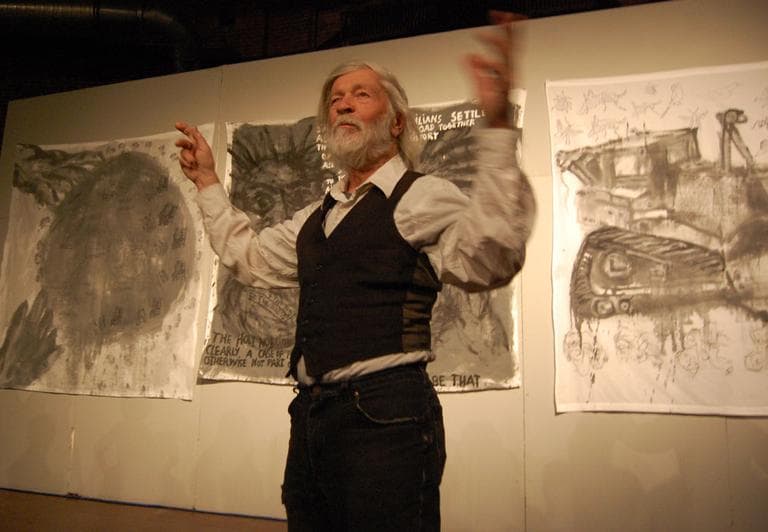

Schumann enters with a fiddle and music stand and sets up amidst the bodies. “And now they need to be addressed, these bodies, downed by the battle of history and stupidity, but obviously not really finished,” he says as he scratches out notes. “Even as they are lying there, they’re already confronted with larger as yet unfought battles and the likelihood of self-produced disaster. They must now be addressed with the Possibilitarian imperative to rise up to their past battle history existence.” He urgently saws on the violin. “To tell their muscles to get ready. To tell their voices to train for the new battle cry, the anti-disaster battle cry, the battle cry that life demands of them to realize the Possibilitarian word, the possible world that the disaster world needs.”

“Up and at ‘em,” he concludes. “Up and at ‘em!” the dead on the floor shout. Before anyone moves—but with a jolt of hope, you’re certain they’ll hop back to life—the lights blackout and the show ends.

At age 78, Schumann remains one of the world’s great masters of art. And he happens to be one of New England’s own. And still producing.

Decades after Bread and Puppet’s beginning, they continue to challenge the conventions of theater and use its methods and stories to critique the failings of our society. They speak in a moral, prophetic voice. The Boston Center for the Arts shows demonstrate a master continuing to explore his central motifs—sustainable communities, the tension between the rich and the 99 percent, war and death, resurrection and love—with his group dances and awesome, giant puppets.

The evening’s paired performances offers a glimpse into the evolution of Schumann’s style—the silent Asian-inspired pageantry of early Bread and Puppet Theater, which over the years has expanded, grown more epic, and added European clowning.

Bread and Puppet continues to present large politically engaged outdoor spectacles, participate in regional parades, march in protests, and launch national tours. Shows from the past decade have addressed the Sept. 11 attacks, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, American torture, the economy, and PFC Bradley Manning, who is charged with revealing classified reports of U.S. military and diplomatic efforts to WikiLeaks.

The theater’s influence is profound. The giant puppets that routinely appear at public protests and marches are descendents of Bread and Puppet—often directly because company alums have started their own theaters around the world, and due to the theater’s long tradition of incorporating untrained volunteers into their performances wherever they goes.

In the Diggers, Schumann finds rhymes to Occupiers’ recent calls for economic justice from America’s public squares. The utopian remedies the Diggers, the Occupiers and Bread and Puppet Theater variously propose can feel impossible, or to say the least impractical. In Schumann’s work, utopia is always small, sharing, pre-industrial farming communities. But these voices challenge us in these United States to continue to shape, to invent a more perfect, more equal Union.

This program aired on January 26, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.