Advertisement

Diversity On Display At Lyric Stage, Company One

BOSTON — There's been an explosion the past two years of plays showcasing the area’s increasingly talented minority actors. It's not as if this is a new phenomenon, but there does seem to be more of a concerted effort throughout the theater community to reflect present-day Boston and Obama-era America. Almost all the small and midsize theaters deserve credit, but two of the leaders in the effort have been Company One and the Lyric Stage Company, both of whom have just opened plays not only starring people of color, but written by them.

Both come with impressive credentials. Quiara Alegría Hudes’s “Water By the Spoonful” at the Lyric won the 2012 Pulitzer Prize. She also has a Tony nomination for her book for “In the Heights.” “Splendor” at Company One is a world premiere by highly acclaimed local playwright Kirsten Greenidge, whose “Luck of the Irish” played at the Huntington Theatre Company before moving to New York.

The two plays are receiving strong, imaginatively staged productions. Director Scott Edmiston cuts to the emotional core, as he always does, in the sparely-designed “Water By the Spoonful” at the Lyric. Shawn LaCount, the creative head of Company One, brings out a more physical intensity in “Splendor” and both have assembled white, black, Asian and Latino/a actors who could be rising stars locally. (Some, like Johnny Lee Davenport at the Lyric, already are.)

“Water By the Spoonful” (through Nov. 16) is the middle part of a trilogy, though you don’t need to see the first. (The Lyric is doing a reading of it: “Elliot, a Soldier’s Fugue” Nov. 12.) The unifying subject here isn’t race, but drug addiction. Five of the seven characters have drug problems and four of them are part of an addiction chatline.

I’d be curious if the Pulitzer voters saw the play or, as is often the case in play competitions, only read it. Unlike most plays, I suspect this one reads better than it plays, despite the efforts of Edmiston and cast. The problem is mostly in the first act in which the chatters act out their chatting, which can sound awfully artificial:

“Once upon a time I had a family. Now I have six years of being clean.”

“My brain is my biggest enemy, arguing my soul into a corner.”

“Sigh.”

Even the non-chatting dialogue can sound stiff. Aside from the chatters there is the Ortiz family gathering for the funeral of the matriarch. Yazmin, a niece, is at the florist with her cousin noting that the flowers, too, are going to die and tosses in what the funeral home’s motto could be: “Would you like some death with your death?”

The revelations, too, seem a bit forced, as when the chat leader arranges for both one of the chatters and her son to come to a diner at the same time. Chaos conveniently ensues.

Here's that scene from the original Hartford Stage production with a coarser chat leader:

Fortunately, things steady themselves in the second half. The revelation alluded to, which I won’t spell out, is searing, and does underscore the title as well as the basic theme of people needing to “water” each other. It’s a basic message of nurturing, but in this age of disconnectedness and distress it bears repeating, and dramatization.

Hudes also makes provocative use of John Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme,” talking about his progression from dissonance to, a year later, free jazz in “Ascension.” Freedom’s just another word for ... junk? Noise? Or acendance/transcendence? Discuss.

The characters in the play are Puerto Rican, Japanese, Iraqi, African-American, and, yes, white. It feels like 21st century America trying to find connectedness among each other, despite all the barriers and tragedies in their way. Edmiston and the cast certainly find it in their chemistry; Emerson graduate Theresa Nguyen stands out as a particularly bright prospect.

Some of this connectedness feels a little pat, but most of it is genuinely moving. I don’t think the writing is Pulitzer material, but by the end the play’s a winner.

“Splendor” began life as a well-received one-act play, “Thanksgiving,” centered on three white working-class women and Fran, an offstage daughter of a black man and Italian woman. Fran is now the central character of the expanded play, “Splendor,” and while she is full-bodied, the play is not.

Greenidge is not alone in refusing to let sleeping one-acts lie. One of the best, Edward Albee, weakened “The Zoo Story,” by adding a first act almost 50 years later. I didn’t see “Thanksgiving” so I can’t judge the original’s merit, but the episodic “Splendor” feels too contrived. The fictional town of Bellington, as in “Luck of the Irish,” stands for one of the Massachusetts cities or towns near Cambridge, such as Medford or Watertown, though it feels more small-town.

Which makes you wonder why of all the gin joints in the country, the recently-divorced, cosmopolitan Fran would move back to a place where she loathes just about everyone (including her obnoxious mother) and almost everyone loathes her. She earned the town’s wrath by lobbying to get the high school football team’s name changed from the Chiefs to the Trojans because of the former’s offensiveness to American Indians. Something bad happened to one of the players and she became persona of color non grata.

The confrontations in the play, though, seem rooted more in class than race, which is all to the good because as Howard Zinn used to say, Americans have a tougher time talking about class than race.

I don’t know, though, that Greenidge advances the conversation. Her Irish and Italian working-class characters seem like stick figures as they lament Foodmaster becoming Whole Foods and gravitate to Dunkin’ Donuts instead of Starbucks. And even though they “all voted for Obama” their lives are achingly stuck in resentments of the past. Greenidge, to be sure, acknowledges how today’s economy has constricted their lives but there’s not a lot of dramatic pop in these scenes.

LaCount, though, makes excellent use of the constricted space as there is pop in the structure and staging, beginning with a searchlight scanning the various characters we’re about to meet, assembled beyond the top row of the Plaza Theatre at the Boston Center for the Arts (through Nov. 16).

The two most interesting characters are Fran and Nicole, the white woman who had been her best friend until Fran showed up at the Thanksgiving football game despite the controversy she started. The play intriguingly goes back and forth in time, each episode taking place on the day before Thanksgiving as well as on the holiday.

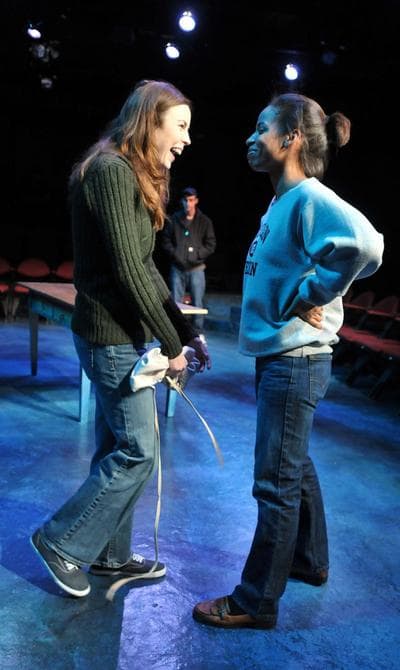

The flashbacks between Fran and Nicole are the most convincing and the most moving, in no small part because of the talent of the two actors, Alexandria Danielle King and Molly Kimmerling. Nicole is not a stick figure; her yearning for something better, including UMass, makes you feel her pain.

Fran, sporting an Oberlin sweatshirt, seems to have a good relationship with her brother, Anthony (nicely played by Danny Mourino), but the rest of the town or city can’t have anything to offer her at this point besides misery. They also don’t have anything to offer the play. It might have made more sense for Fran and Nicole to have met at a funeral and then look back at their lives. This Thanksgiving dinner seems like empty calories except for what Fran, Nicole and Anthony bring to the table.

Even with disappointing material, however, the talent of cast, black and white, signals good things ahead for the Boston theater community, as does "Water by the Spoonful."

This program aired on October 23, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.