Advertisement

Visionaries: For Surgeon, Face Transplants Help Patients Emerge From 'Social Death'

Resume

Our faces are intimately connected to our identities. They show our emotions and help us present ourselves to the world. If you think about your face being destroyed, it's easy to imagine how your life could fall into darkness. That's what motivated Dr. Bohdan Pomahac to lead a campaign to do face transplants at Boston's Brigham and Women's Hospital.

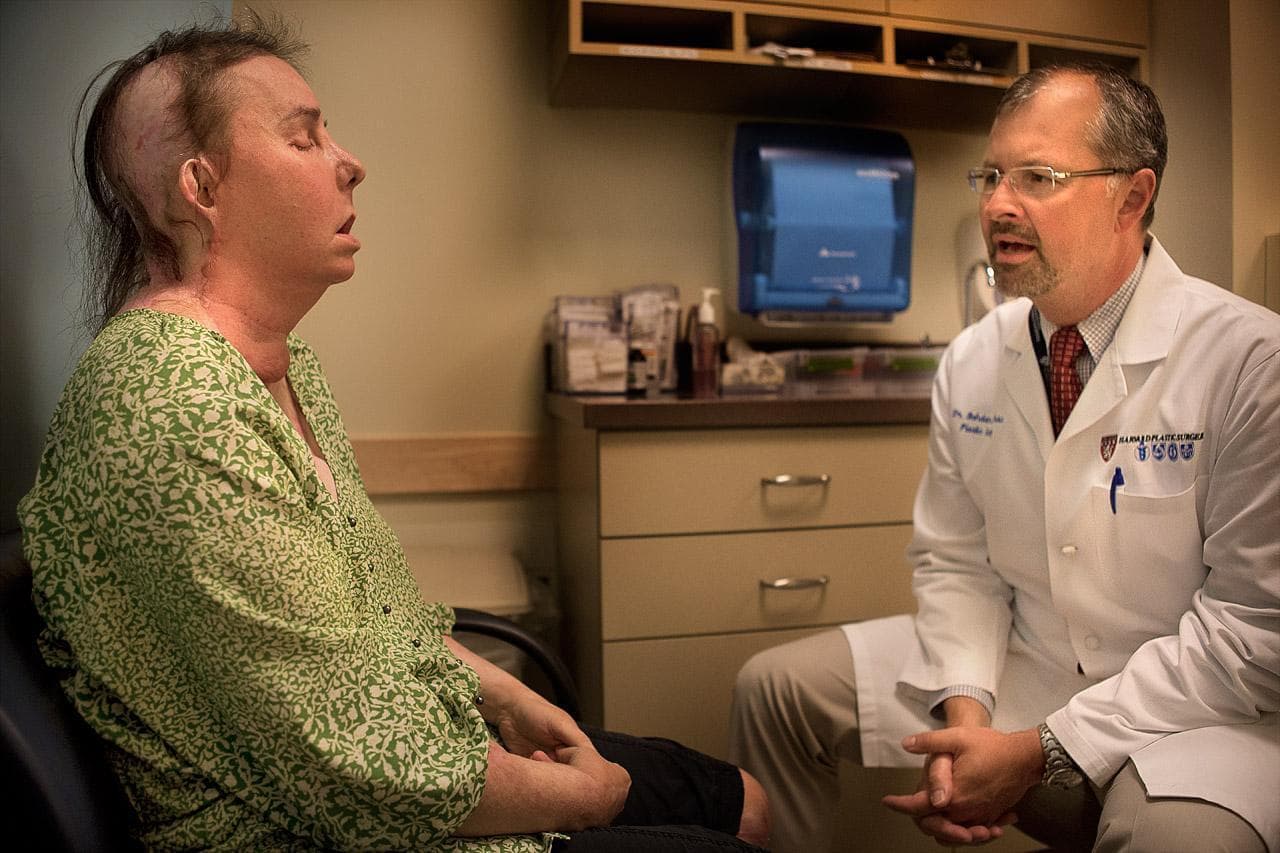

BOSTON — The simple act of smiling — it's not so simple for Carmen Tarleton. But her plastic surgeon is glad to see it's getting easier.

"And give me a big smile now," Pomahac instructed Tarleton during one of their recent appointments. "Yeah, the left side is starting to pull."

Tarleton's face is not the one she was born with. In February, Pomahac transplanted her new face from a deceased donor in her 50s onto Tarleton, a 44-year-old former registered nurse and mother of two. That was six years after her estranged husband beat her with a baseball bat and doused her with industrial-strength lye, dramatically disfiguring her and burning 80 percent of her body. It was the fifth face transplant Pomahac performed at Brigham and Women's Hospital since 2009.

"We take it for granted that you in the morning look briefly at your face and fix your hair or whatever, but you interact the entire day with other people and you're used to just normal reactions," Pomahac said. "These [face transplant] patients are used to these horrified looks and isolation. They can't eat outside. They drool. They can't smell. You kind of realize that the life without [a] face is essentially social death."

'You Have To Prove Yourself In The Big World'

At 42 years old, Pomahac sports a graying goatee and glasses, and reveals a gentle, modest demeanor. But his unassuming presence belies a fierce determination and focus.

In 1996, one day after graduating from medical school in his native Czech Republic, he packed up and flew to Boston, where he had previously spent a brief time during a medical exchange but knew no one and had no work or schooling lined up.

"One day he just showed up without an appointment and he offered to work for no pay, and I told him that was a bad idea," recalled Dr. Elof Eriksson, chief of plastic surgery at the Brigham.

So impressed by that move, Eriksson hired Pomahac to work in his lab for a small salary.

Pomahac attributes his ambition to growing up in communist Czechoslovakia, where his father, a chemical engineer, was persecuted for signing a declaration against the communist party and therefore could only find odd jobs outside his profession.

"So he kept emphasizing to us, his sons, that we should learn language, that we should think beyond the Iron Curtain," Pomahac said. "So I was primed to just go out and explore."

And he got his chance. Just as he was starting medical school in 1989, the non-violent Velvet Revolution took place. Pomahac helped organize student demonstrations. The communist leaders resigned, meaning the system that had been limiting him his whole life was gone.

"You have to prove yourself in kind of the big world, and it puts a lot of pressure on anybody," he said. "You have to always have the feeling, 'I have to work extra hard. I cannot be just as good as anyone in Western Europe or the U.S.,' but you have to be better."

'Is That All You Can Do?'

Pomahac's drive showed itself early in life. He knew late in elementary school that he wanted to be a surgeon — to use his hands and his brain to help people.

Once he got into the surgical residency program at the Brigham, he knew plastic surgery was his calling because, he said, he could really be creative and innovative. And he quickly zeroed in on the face.

"I think it's the most fascinating part of the human body that one can work on. And it's so intricate and so specialized, so unique," Pomahac reflected. "It's so hard to get it right, to do the reconstruction well. So I was all fired up about that."

He tried many operations to improve different parts of Tarleton's face in the years after she was attacked.

"The ideas he had about certain surgeries to try and help me were creative," she said. "And even though they didn't all work, it was always worth the risk."

But the more times it didn't "work" with his burn and trauma patients, the more frustrated Pomahac became.

"Patients were often still looking very deformed, and many times the goal was shifted from reconstruction to more wound control," he explained. "My wife is a physician, as well. So sometimes I was very happy about the result, I showed her a picture and she was like, 'Is this really it? Is that all you can do?' "

Ultimately, it wasn't all he could do. The world's first face transplant, a partial one, happened in France in 2005. And Pomahac, still a junior doctor virtually unknown in local medical circles, wanted to do the same thing here. His mentor, Dr. Eriksson, was one of his earliest champions. But there were others who needed convincing.

"There were not only skeptics; there were naysayers," Eriksson said. "We talked frequently about this, and I was trying to do my best to cheer him on and support him."

Through a long, painstaking process, Pomahac addressed the ethical questions raised by the hospital's administrators and review board: How would patients be psychologically impacted by having someone else's face? Would a transplanted face transport some of the donor's identity along with it?

"People were concerned that we may be creating, essentially, dead people walking again," Pomahac said.

He and his colleagues worked up computer simulations to dispel that worry.

But there were more. Since a new face isn't needed in order to survive, would it be right to subject a patient to risky lifelong immune suppression medications? Also, the deceased donor's face would need blood flow up until the last minute, so it would have to be recovered before the heart and other vital organs. Pomahac pledged he would step aside if there were complications, so surgeons could retrieve the life-sustaining organs for other patients. He and his colleagues were virtually designing the face transplant operation from scratch, he says — something surgeons don't often get to do.

"How do you recover the face? What do you include? Just taking a piece of tissue doesn't mean that you can just put it on and it would live," Pomahac explained. "You have to think through individual steps. So that process was probably most challenging, but also most fun to work on."

In 2009, all the work paid off. Pomahac led a team of surgeons on a partial face transplant for a man who had fallen on the electrified third rail in a MBTA station. They followed two years later with the country's first full face transplant and they've done three since, making the Brigham the leading face transplant center in the U.S.

The video from Tarleton's 16-hour face transplant shows Dr. Pomahac's calm, deliberate and humble manner. Though he is in charge of the surgery, he frequently takes a step back for a colleague to lead a portion of it. He works with a team of extremely skilled surgeons, he points out. They delicately connect dozens of arteries, veins, nerves, soft tissue and muscles.

Next, Trying To Eliminate The Need For Lifelong Transplant Drugs

His life outside the operating room is quite the team effort, as well — and he acknowledges it's a tough balance. He has two kids in grade school. His wife gave up her medical career to manage things at home.

He spends about 80 percent of his work time in the operating room or in clinic visiting patients. The other 60 percent is spent on research. You'll notice, he jokes, that that adds up to 140 percent.

Among his many research projects, Pomahac is working on ways to help the body build permanent tolerance for transplanted tissues — ultimately eliminating the need for lifelong immune suppression drugs.

"Then I see that not only [the] face but [a] variety of sort of body-restoring operations will be feasible," he said. "And that's really what will scale it up from [a] few individuals with the most tragic injuries to technology that can help thousands or perhaps hundreds of thousands of patients."

Soon, Brigham surgeons will start doing leg transplants. Pomahac will play a role, but his focus will remain on the face. Several more candidates are waiting for donors. And he's closely monitoring the progress of the five patients who've already received new faces.

In one of his many follow-up appointments with Tarleton, he asked if she felt well.

"I do. I feel better and better," Tarleton responded. "And I'm learning to play banjo, so one of these days I'll play you a banjo song."

"Wow!" he replied, adding that Tarleton is doing a great job learning the piano, as well.

Dr. Pomahac calls the face transplant recipients his patients for life.

"They all have my cellphone. They all have direct access to me at any time," he said. "I'm almost like their personal doctor. Whatever problem they have, they can and they do go directly to me."

He feels responsible for their success and any setbacks, he said. And though their new faces didn't save their lives, he's thrilled they have gotten their lives back.

Brigham and Women's Hospital covered the cost of the first face transplant; Dr. Pomahac and the other surgeons donated their time. Since then, a Department of Defense research grant has covered the cost of the operations, and that grant was just extended until 2015. Dr. Pomahac hopes in the future, face transplants will be covered by insurance companies.