Advertisement

7 Reasons To Love 'The Complete Coens' At The Brattle

With the Brattle Theatre presenting a Coen brothers retrospective to coincide with the release of their latest film, “Inside Llewyn Davis,” I thought I should add my list of The Top 10 Coen Brothers Films to the hundreds out there on the Internet. So what’s stopping me? Well, I just can’t make up my mind. Instead, here are seven reasons why the Coen brothers are great filmmakers.

1. They are great collaborators and craftsmen.

Together Joel and Ethan Coen produce, direct, write and under the pseudonym Roderick Jaynes, edit their films. The Coens do meticulous storyboarding and advance planning. On the set there’s little room for improvisation — every word, pause and stutter is scripted.

The brothers’ disciplined yet collaborative approach has attracted a wealth of talent behind and in front of the camera, including longtime cinematographer Roger Deakins, composer Carter Burwell, and actors John Goodman, George Clooney, Steve Buscemi, Frances McDormand, John Turturro and Jeff Bridges.

2. They were ahead of their time.

When the Coens first appeared on the scene with “Blood Simple” in 1984, a sense of irony and detachment was just beginning to seep into the popular culture. Today, the Coens’ early films don’t merely hold up, they seem richer and stronger now that we are more attuned to their dark, idiosyncratic humor — the surreal juxtapositions, the graphic violence that’s both terrifying and funny, and the films’ self-reflexiveness.

3. They are American masters and masters of Americana.

The Coens have created a distinctive body of work that offers a provocative, idiosyncratic and sweeping vision of America. The films are grounded in American time, place and movie genre, but wildly re-imagined.

Partial to crime stories and film noir, the Coens have also put their spin on Westerns, horror movies, screwball comedy and gangster films, and they seem to delight in having two or more genres knock up against each other in a film.

They also draw heavily and often explicitly on film classics and literature. To take but one example, “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” (2000) is a comic road/chain gang movie set in Mississippi during the Great Depression. Loosely based on Homer’s “The Odyssey,” with a title that calls out to Preston Sturges’ “Sullivan’s Travels” (1942), the film has elements of magic realism, and scenes with the Ku Klux Klan modeled after scenes in “The Wizard of Oz” (1939). The film presents a rich selection of American folk, bluegrass and blues songs, produced by T-Bone Burnett, that comment on and propel the story.

4. They give us memorable characters.

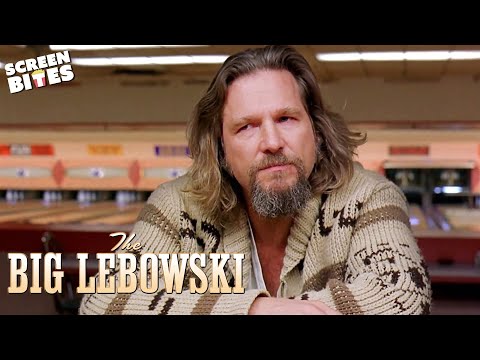

Who can forget The Dude and Walter Sobchak from “The Big Lebowski” (1998)? There’s no question that the Coens are fond of the many dummies who populate their films: yokels, schlubs, losers and fools who act impulsively, make terrible choices and whose plans go horribly awry.

And, oh my, how these characters can talk! The Coens delight in pairing a yacker with a near mute such as the murderous duo in “Fargo.” There are highfalutin talkers, the most extreme being Professor G.H. Dorr (Tom Hanks) in “The Ladykillers” (2004); the Naif (Tim Robbins) who waxes poetic about the circle of life and hula hoops in “The Hudsucker Proxy” (1994); and wordmeisters like Miles Massey (George Clooney) in “Intolerable Cruelty” (2003) who can spin verbal gold out of baloney.

Then there are the villains, the scariest and most evil of them being Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem) in “No Country for Old Men” (2007).

5. They constantly take us by surprise.

The violence in Coen brothers films tends to be graphic, senseless, terrifying, and most disturbing of all, sometimes mordantly funny. Taking first place in the category of Most Bizarre Murder Weapon is the cattle gun in “No Country for Old Men.”

Along with unforgettable characters, the films offer indelible images: a fedora floating into the forest, a leg sticking out of a wood chipper, men sitting behind large desks, Dapper Dan pomade cans, a baby in his car seat in the middle of the road, and bellboys in funny little hats.

6. Their films operate on different levels.

Coen films can be taken as works of auteurs, slices of Americana, cultural commentaries, visual feasts, reflections and shapers of the zeitgeist, and treasure troves of intertextuality. They also raise philosophical questions about the nature of truth and the meaning of existence. Werner Heisenberg played a role in “The Man Who Wasn’t There” (2001) years before he and his Uncertainty Principle figured in “Breaking Bad.” But count on the Coens to make fun of and undercut the seriousness of any philosophical musings.

7. Their films are entertaining.

Their films can also be taken as pure straight-up entertainment, auteurship be damned. This is no small thing, and from the way the Coen brothers reluctantly, but very amusingly, talk about their films and characters in interviews and DVD bonus material, it’s clear that they make films to entertain themselves.

All that said, if I absolutely had to list my favorite Coen brothers films, if somebody were threatening to cut off my toe, then I guess I’d admit to favoring “Fargo.”

“Fargo” is their most accessible neo-noir (a noir born after the late 1950s) and one of their most popular films. This is due in large part to the character of Marge, the pregnant Brainerd chief of police, who gives the film the heart that critics had heretofore accused Coen brothers’ films of lacking. A film blanc (film noir in a winter coat) that’s set primarily in the Coens’ home state of Minnesota, “Fargo” is unusual in that it’s shot naturalistically, opening in a blinding snowy landscape, with no visible horizon.

Everything that can go wrong does when an ineffective car salesman in deep financial trouble hires a pair of thugs to kidnap his wife so that he can collect the ransom from his rich father-in-law. The film exposes the dark underbelly of “Minnesota nice” and a great emptiness that’s afflicts the country, where everyone’s brain is snowed in by TV. By the film’s end the question remains: Is it enough that Marge is good, that she is in a loving relationship with a child on the way, that she just doesn’t get the evil in the world? Or is the warm and cozy quilt that she and her husband cuddle under, in the end, cold comfort for the viewer?

I’m partial to noir and to having my mind messed with, ergo I am partial to “The Man Who Wasn’t There,” the most noir of the Coen films. Filmed in gorgeous black and white, it features barber Ed Crane, a “nobody,” who blackmails his wife’s lover to get cash so he can go into the dry cleaning business. Played to perfection by Billy Bob Thornton, Ed doesn’t say or express much, his most dramatic gesture being a slight nod. At the same time, this most-silent of protagonists is our not-so-silent narrator.

Set in Santa Rosa, Calif. in the late 40s, when the specter of the atomic bomb loomed, the film veers off at times into sci-fi. Not one of the Coens’ most enthusiastically received films, critics have, to my mind, wrongly accused it of being long on style and short on substance, a common criticism of the Coens’ work.

Like “Fargo,” the film questions the nature of truth in storytelling. “Fargo” opens with a title announcing that the film is based on a true story. It’s not, but most people fall for it. At the end of “The Man Who Wasn’t There,” Ed informs us that he’s sold the story he’s telling us to a men’s magazine, raising questions about all that’s gone before.

But wait, now that I think about it, “A Serious Man”(2009) might be my favorite Coen brothers film. Or maybe it’s “Miller’s Crossing” or “Blood Simple” ... the list goes on. What’s your favorite?

Kaj Wilson hosts The Breakfast Film Club at The Coolidge Corner Theatre. She is the former artistic director of The Boston Jewish Festival. Reach her at kajwilson@yahoo.com

This program aired on December 10, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.