Advertisement

After 20 Years, Menino Leaves A City Strong But Flawed

Resume

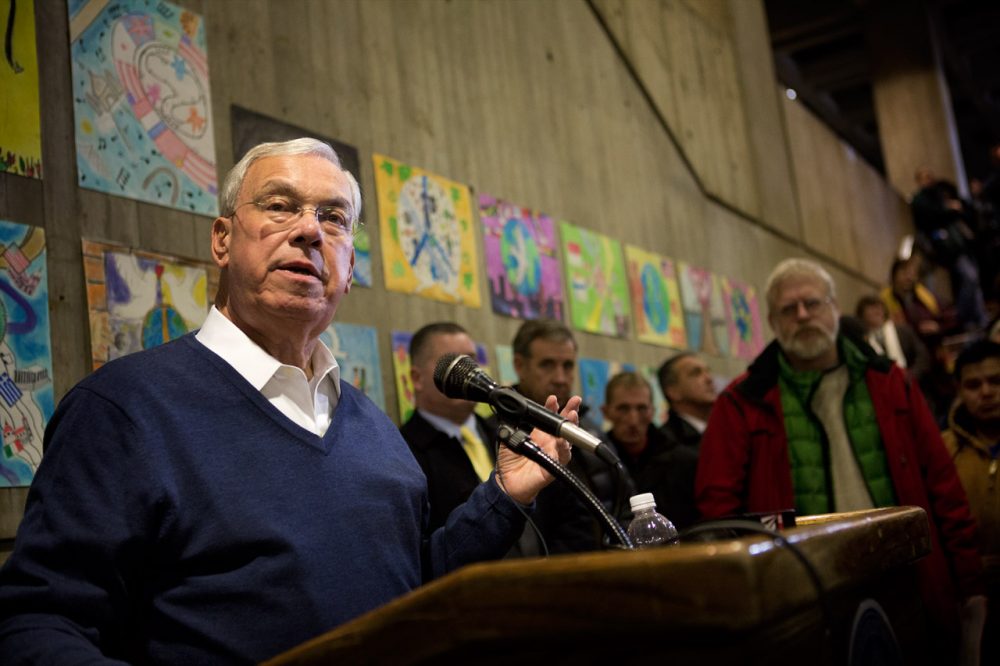

Mayor Thomas M. Menino stood at a podium at Faneuil Hall — his wife Angela, his two children and his six grandchildren at his side.

Below: a governor and a U.S. senator. City Hall secretaries and union workers.

"I'm here with the people I love," Menino said that day in March, "to tell the city I love, that I will leave the job that I love."

And so began Boston's attempt to measure the legacy of its longest-serving mayor, 20 years after he stepped into the corner office.

Menino, who turned 71 last week, leaves a city undoubtedly stronger than the one he inherited.

There is a new park in West Roxbury on the site of an old dump. New storefronts where grates once stood in Roslindale Village. Gleaming new office towers in a long-forlorn stretch of South Boston now known as the Innovation District.

But success has bred real problems: growing inequality, housing prices beyond the reach of most families. These are problems that Menino's successor, Marty Walsh, will have to confront in the coming years.

But polls show that Mayor Menino is leaving office an enormously popular figure — king of this cosmopolitan city — an unlikely perch for an inarticulate politician from the far reaches of Hyde Park.

From The Neighborhood

Menino got the political bug when he was 13 years old, handing out campaign literature for a friend of his father.

Six years later, at a Park League Baseball game at Kelly Field, he met a city council candidate named Joe Timilty who would play a pivotal role in his early career.

Menino worked on Timilty's three unsuccessful campaigns for mayor and then served as an aide in his state Senate office, tending to the needs of constituents in Hyde Park and beyond.

When the state Legislature expanded the Boston City Council in 1982, Timilty created a Hyde Park-Roslindale seat that seemed almost tailor-made for his longtime aide.

"It was carved out for him specifically," said Timilty in a recent interview.

With that, the behind-the-scenes operative became a candidate.

A 1983 WGBH television documentary found Menino waging his first campaign for the council — and already slipping into the malapropisms that would define his regular-guy mayoralty.

Menino rehearsed his announcement speech in a wood-paneled living room. "It will demand someone who understands those issues, like physical policy," he said.

A pair of aides, including his wife, Angela, corrected him; he meant to say "fiscal."

But the documentary also showed a man with a firm grip on the nuts and bolts of local politics — a talent that would earn him the nickname "the urban mechanic" and the loyalty of thousands of voters.

Menino served on the city council for a decade — he spent much of it perched in a window seat at the Bostonian Hotel, rapping with business leaders and journalists about how the city worked.

He won the city council presidency by a single vote in 1993. And when Mayor Ray Flynn left to take a post as ambassador to the Vatican, Menino became acting mayor.

At first, he was not considered a favorite in the race to succeed Flynn. Most saw him as a caretaker. But Menino made skillful use of the office. One of acting mayor's first moves: a freeze in water rates.

"He took the acting out of the mayor," says longtime political adviser Robert "Skinner" Donahue. "He just assumed the position."

Menino finished in the top spot in the preliminary mayoral election and swamped Jim Brett in the final election. Over the next two decades, no one would ever come close to beating him.

The new mayor inherited a city just pulling out of a sharp recession — just rebounding from the aftershocks of the racially charged busing crisis of the 1970s and the white flight that followed.

One of the first problems he confronted was an uncertain future for Boston City Hospital, a public institution that served the poor.

Menino oversaw a merger with the private Boston University Medical Center — a task complicated by fears that the new Boston Medical Center would lose the public hospital's sense of mission.

Those fears would eventually wither away. A glass and brick entryway to the hospital now pays homage to his accomplishment: the Menino Pavilion.

The new mayor also faced a troubling spike in violent crime in neighborhoods like Four Corners in Dorchester.

"When Mayor Menino comes into office, in Four Corners there were young men that would stand out on the roofs at Algonquin and Bradley with AK-47s and shotguns — right up in the roofs — and patrol a major, kind of, crack cocaine drug cartel," says the Rev. Eugene Rivers, who was a central figure in the fight against gang violence at the time.

The violence came down sharply in the mid-90s.

Part of it was a natural decline from the high murder rates of the early part of the decade. But criminologists say heightened cooperation among ministers like Rivers, city government and law enforcement contributed to the "Boston miracle" — a 29-month stretch when not a single minor was killed by a gun or a knife.

Rivers gives Menino credit for curbing the violence — murder is down 60 percent since he took office — and, more broadly, for leading Boston to greater safety and prosperity. And the city's black and Latino neighborhoods have rewarded the mayor handsomely over the years with strong electoral support.

But Rivers, and others in Boston's minority communities, lament the city's growing economic inequality — a problem Menino himself has acknowledged in his closing weeks in office.

"It's painful, quite frankly, to see the rest of the city a bit more prosperous than where you, yourself, live," says Rodney Singleton, an engineer and community activist in Roxbury. "That doesn't sit well. It really doesn't."

One of Singleton's chief concerns is education.

The Schools

In 1996, in his State of City address at the troubled Jeremiah Burke High School, Menino pledged to improve the schools.

If he failed, he told the audience, "then judge me harshly."

The schools have improved in the last 20 years: test scores have shot up in certain grades, dropout rates have declined to historic lows.

But the achievement gap separating white students from their black and Latino peers remains stubbornly wide.

Education reform advocates like Paul Grogan, president of the Boston Foundation, say Menino moved too slowly to embrace systemic reform — to challenge the teachers union, wrap his arms around charter schools and push more power to principals.

"No doubt the schools have improved under his leadership," Grogan says. "But he stayed very long with what I call the incremental approach — really wanting to believe that the system could retain the structure that it's had and systematically improve over time. And that really hasn't occurred."

Menino acknowledges the unfinished business of the schools. But he suggests there are limits to what an urban school district can do.

"The difference is when you look at the Boston Public Schools, any public school system, we take all the kids — special needs kids, English learners," he says. "Every kid who walks through the door, I educate. That's my challenge."

But if progress has been uneven in places, there have been some unmistakable triumphs.

Mechanics

When Menino first ran for city council in 1983, he campaigned on turning around an area then known as Roslindale Square.

It was not the most welcoming place back then. There were muggings. Grates came down at night. Street lights coated the area in an orange haze.

Menino's idea was to bring in the National Trust for Historic Preservation's Main Streets program, then focused on revitalizing commercial districts in small towns.

Roslindale Square would get the first urban Main Streets program in the nation. And over time, city government, Main Streets and Boston's growing economy turned the place around.

There was an overhaul of the municipal parking lot and a farmer's market. Grants for new storefronts, arty signage and a whimsical sculpture.

Now, Roslindale Village boasts a high-end cheese shop and a bistro serving up salmon with an apricot candied jalapeno crust.

Just down the street: Centre Cuts Salon & Spa in Roslindale Village, with waxing, massage and pedicure rooms — the latter modeled after an old Italian villa.

Charlie McCarthy, co-owner of the spa, says the mayor has seen to daily cleaning and speedy graffiti removal. "It's the little things," he says.

The turnaround has come at a cost: over the last 20 years, the median price of a one-family house in Roslindale has more than tripled to $407,500, according to the Warren Group.

But the urban mechanic, making full use of his lengthy tenure, slowly turned a drab square into an upscale village.

Downtown

The flashier development has come downtown. After years of delays at the site of the old Filene's department store at Downtown Crossing — delays that left an embarrassing hole in the ground — a 625-foot tower is rising.

And an entire district — the Innovation District — is going up on the South Boston waterfront.

Bruce Katz, co-author of "The Metropolitan Revolution," says most innovation districts grow up around hubs like a university or medical campus.

Here, it was different: a new neighborhood on a barren stretch of the waterfront. And the mayor, he says, gets credit for relentlessly marketing the idea in the face of skepticism.

"In Boston, Menino almost willed a new district to attract companies and allow for this sort of new entrepreneurial space," he says. "Even the design of buildings allows for greater collaboration, greater innovation within and across companies."

Development has been a thorny issue for the mayor. Critics say he's favored certain developers and exercised too much control.

Menino poked fun at himself a few years ago when he struck a Godfather-like pose in a video spoof, stroking a cat while talking to a developer.

But critics say his tightly controlled approach to development has had real consequences: drab architecture and hefty tax breaks that have shortchanged affordable housing programs.

And observers say the mayor gets only partial credit for Boston's building boom.

The last 20 years have a seen a broad revival of the American city, after all, with business and the larger culture placing new value on the density and creativity of urban spaces.

Metropolitan Boston's economy has grown a healthy 80 percent since Menino took office, according to IHS Global Insight. But cities like Atlanta, Seattle and San Diego have grown just as fast in that period.

And Grogan, of the Boston Foundation, says the city was especially well-suited to the rise of the innovation economy.

"There's no place like Boston," he says. "We have eight major research universities in the metropolitan area. We have 15 teaching hospitals. Those things came to be valued even more by the global economy. So, the mayor didn't have anything to do with creating that infrastructure, it was there."

"The mayor has done the blocking and tackling of city government very, very well," says Grogan. "Which enables us to realize the benefits of those other trends."

Grogan says the mayor has balanced the budget, avoided scandal and seen to public safety — the baseline for a strong city.

And so the "urban mechanic" — a man attuned to potholes and street signs and city budgets — was able to preside over a transformational period in the city's history.

Menino's own polling suggests he could have remained at the helm — he could have won re-election this fall, as he always did.

But a series of ailments slowed him down and took him away from his famous non-stop schedule of ribbon cuttings and school plays.

And one night in early March, sitting by himself at the city-owned Parkman House where he was recuperating from his latest illness, he decided it was time to go.

The mayor sat with it for a few days. And then he started calling close friends and advisers.

Former chief of staff David Passafaro says he knew the mayor might step down. "When he said it out loud," Passafaro says, "I have to say that it still hit me like a ton of bricks."

A Final Appearance

The mayor's farewell speech at Faneuil Hall seemed destined to be the emotional peak of Menino's final months in office. But the Boston Marathon bombings put him front and center one last time.

He learned about the attack in his hospital room, surrounded by a handful of advisers. He says he asked for the police commissioner on the phone and told everyone in the room to remain calm.

In the days that followed, he checked himself out of Brigham and Women's Hospital several times to attend briefings and press conferences — a hospital bracelet was still dangling from his wrist.

Then, at the Cathedral of the Holy Cross, he pulled himself out of his wheelchair, grimacing, and stood on a broken leg.

His voice hoarse, he delivered the sort of speech this son of Hyde Park had never quite managed before — stumbling a bit, as always, but with a certain clarity. A wounded mayor tending to a wounded place.

"Love has covered this resilient city," he said. "I have never loved it and its people more than I do today."

This segment aired on January 3, 2014.