Advertisement

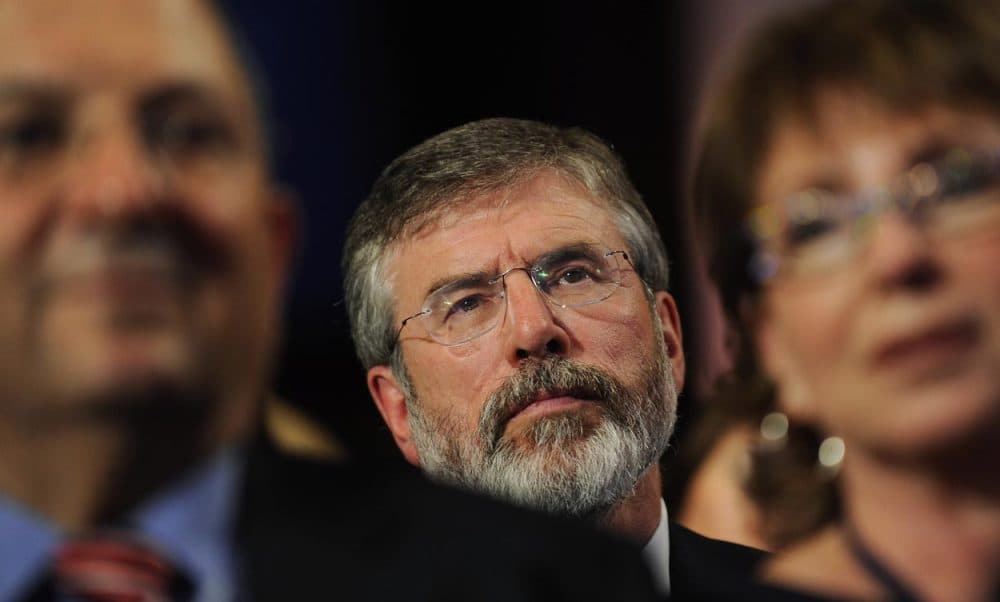

Gerry Adams Arrest 'A Wake-Up Call' For Oral Historians

Resume

The recent arrest of Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams in Northern Ireland has academics reviewing their responsibilities in recording history.

The arrest renewed questions about a supposed confidential audio archive at Boston College, known as the Belfast Project. It contained recorded interviews with people directly involved in the violent, three-decade-long Troubles in Northern Ireland.

The fate of the project and work on oral histories are now being reexamined.

The Treasure Room

On the Boston College campus is the John J. Burns Library. It's a gothic, stone building where rare books, special collections and religious artifacts are kept.

The most precious are protected in the Treasure Room, stored in state-of-the-art, climate-control conditions under the watchful eye of cameras. And in the Treasure Room is a very special area, accessible to only four people with a secret code and special key. Here are stored the Holy of Holies: an audio archive known as the Belfast Project.

A guard on the first floor welcomes visitors.

“Where is the Belfast Project?” I ask. “Where would I find that?”

"You won't find it," the guard says sternly. He gives me the name and phone number of Boston College spokesperson Jack Dunn.

“Well the archive has been closed and no one has had access to it,” Dunn later explained.

The Belfast Project at BC is an oral history collection of ordinary cassette tapes, transcripts and old computer floppy discs — aging media that attempted to preserve a troubling past, but now face an uncertain future.

It was started in 2001, three years after the Good Friday Agreement was signed, ending decades of violence in Northern Ireland between Catholics and Protestants.

Sealed with key and code, the collection contains candid, confessional interviews with 46 former members of the Irish Republican Army and the Ulster Volunteer Force.

The archive came to Boston College because of the Jesuit school's close ties to Ireland and BC's promise to protect the anonymity of those interviewed until their deaths. The first to die was former IRA commander Brendan Hughes in 2008. The film "Voices from the Grave” documents his agreement.

“Do you have a problem with committing all this to secret tape to be used only after you have died?” he’s asked.

“I don't have a problem with that,” Hughes answers. “If I did have a problem with that I wouldn't be sitting here talking to your microphone. I think a lot of the stuff that I'm saying here I'm saying it because I have a trust in you, and I have never, ever admitted to being a member of the IRA. Never.”

Tearing Open Old Wounds

But what began as an oral history archive designed to promote reconciliation in Northern Ireland in the future is now tearing open old wounds.

For the last four years the agreement to keep the tapes secret unto death has been the subject of intense controversy, academic dispute and international litigation.

A federal court forced Boston College to hand over some of its sensitive archive after British authorities invoked a treaty with the U.S. requiring the exchange of information in violent criminal cases.

Now, after another tape was released implicating Sinn Fein President Adams in an IRA murder he denies, Boston College has had a change of heart and is changing the rules for the oral history project, says Dunn.

“If individuals contact us who desire to have their specific interviews returned then we will accommodate them once we verify their names, but there will never be a disclosure of people who participated in the project,” Dunn said.

But that guarantee is not iron-clad. The troubling archive could potentially be subpoenaed again. Dunn won't speculate.

“You know that's something that we'll just see what happens down the road,” he said.

More than 60 nations have signed the international agreement that was used to force BC to give up some of the oral archive. The case sends a message oral historians have heard 'round the world.

“Researchers will always have to be aware of this precedent,” Dunn said. “So if they're recording information on criminal or violent activities, you’re gonna have to be aware of this precedent.”

A Wake-Up Call

“This is highly unusual,” said professor Cliff Kuhn, the executive director of the Oral History Association. “It does provide a wake-up call for archives to really consider now when we do interview people to engage in what we call informed consent.”

Since 1948, when Columbia University created the first academic audio archive, informed consent has been the golden rule for the oral historian: Tell participants in advance how their audio will be used, who has access to it, and don't make promises you can't keep. The Boston College Belfast Project court orders have become a teachable reminder and have shaken up the scholarly staid profession.

“I never thought it would happen,” said Bruce Stave, professor emeritus and director of the Oral History Office at the University of Connecticut. “I think there's, if not a chilling effect, I think there's a cooling of what can be expected in the future. What it's going to do is to make oral historians much more careful about what they record.“

And participants who are recorded will have to be more careful about the agreements they sign, says Stave.

“It may have an impact on the type of projects that are done,” Stave said.

The BC audio archive brouhaha is just one of many recent controversies over the use and control of oral histories. Some 9/11 New York City firemen withdrew their permission making public their recordings, fearful of retribution by disaster deniers.

And just a few weeks ago the heirs of some World War II Nazi prosecutors raised questions about oral histories collected long ago that archivist now want to digitize and disseminate worldwide.

“What to do about those oral histories that were recorded 30, 40, 50 years ago? Do we have permission to put them on the Web?” asked Jayne Guberman, director of the oral history project on Boston's Marathon bombing, a collaborative project with Northeastern University and WBUR. “And now that we can put oral histories online many more people can have access to them, and it's changed oral history in profound ways. I mean I think it adds an ethical dimension that perhaps wasn't there earlier.”

The future of oral history is being tested. The digital world opens the recorded past to a new generation and with it the responsibility to keep promises made long ago.

This segment aired on May 12, 2014.