Advertisement

How The Boston Busing Decision Still Affects City Schools 40 Years Later

Resume

Note: This report contains some harsh language.

BOSTON — On June 21, 1974 — 40 years ago Saturday — Judge W. Arthur Garrity ordered that Boston students be bused to desegregate schools. His decision ignited a firestorm of controversy and violence.

"Busing was one of the biggest events in the history of Boston," said Jim Vrabel, author of the soon-to-be released book, “A People’s History of the New Boston.” The historian puts busing right up there with the American Revolution — though busing in Boston was more a civil war, the battlefield the city, the fight between neighborhoods and neighbors.

"It was so disruptive to the city at the time because it caused so much hard feeling among people and because it has a lasting, I think negative, impact to this day," Vrabel said.

It took Garrity 15 months to decide the case. A third generation Irish-American who lived in suburban Wellesley, Garrity was known as a meticulous, methodical man. His desegregation ruling in the lawsuit Morgan v. Hennigan ran 152 pages.

Some facts are not in dispute. Boston schools were segregated. Some schools in Roxbury were 90 percent black. In South Boston, nearly 100 percent of the students were white.

The Boston School Committee said that was just the way it was; it's where people chose to live. But black parents in the city wanted more for their kids.

"This all started in the black community," Vrabel said, "because although the schools were not providing a good education for anyone, they were providing a particularly bad one for students in the black community."

Some white schools lacked libraries and cafeterias. Some black schools lacked classrooms, books, even teachers. In the mid 1960s, just one Boston school teacher in 200 was black.

Among them was Jean McGuire. "My son went all the way through school 'til he was a senior and never saw a black man — not a custodian, not a teacher, not a counselor," she said. "Can you imagine your kids going all the way through school and never seeing a white teacher?"

At the time there wasn’t a single black principal in the entire Boston school system.

"The reason Boston schools began to deteriorate was that the school system became less of an educational system and more a patronage system," Vrabel said. "Teachers and administrators were hired based on who they knew rather than what they knew."

In 1965 the Massachusetts Legislature passed the Racial Imbalance Act, requiring schools with more than 50 percent of students of one race to desegregate.

Boston's school committee refused to comply. All five members, elected at large, were white.

"It was clear to me when I was hired in 1972 that the day was going to come when the chickens would come home to roost," said Bob Schwartz, who was Boston Mayor Kevin White’s adviser on education when the civil rights lawsuit was filed against the school committee.

Schwartz is now a professor emeritus of education at Harvard University. "At every point where the school committee had a choice," he said, "the school committee opted for segregation."

In 1965 — more than a decade after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that separate but equal schools were unconstitutional — a black parent confronted Boston School Committee member Louise Day Hicks, a staunch opponent of school desegregation:

Johnson: Any school that is predominantly Negro in Boston is an inadequate school.

Hicks: Mrs. Johnson, the superintendent of schools has stated as his policy that a racially imbalanced school is not educationally harmful.

Johnson: Mrs. Hicks, madame chairman, may I say this: Superintendent Ohrenberger and yourself and other committee members do not have children in a racially imbalanced school, so you do not know what the effect is on our children.

"People were tired of fighting and not winning," McGuire said.

"The last 40 years we’ve been pursuing a mathematical solution to desegregate Boston schools, instead of an educational solution to improve them."

Historian Jim Vrabel

She says black parents took matters into their own hands. They boycotted Boston schools and started separate freedom classes for their children. They began organizing buses and carpools to take inner-city black students to suburban white schools.

And finally, black parents and the NAACP made a federal case out of it: suing the Boston School Committee using the state's Racial Imbalance Act.

"And now you had a law that now had teeth to it, but you had to put in the structure that made those teeth bite," McGuire said.

On June 21, 1974, Judge Garrity bit hard, declaring that the Boston School Committee had deliberately created two school systems: one for whites, one for blacks. Garrity’s remedy was busing. He ordered black and white students to attend schools in each other’s neighborhoods.

Ironically, Vrabel says, the school committee had used busing to segregate schools.

"They actively created a segregated school system by using things like busing," he said, "like assigning students to schools outside their neighborhoods, like creating separate grade structures in schools in white neighborhoods and black neighborhoods to artificially create and promote segregation where it might not have existed otherwise."

Garrity began busing that year. He ordered black high school students from Roxbury be bused to South Boston, an Irish enclave, and South Boston students bused to Roxbury.

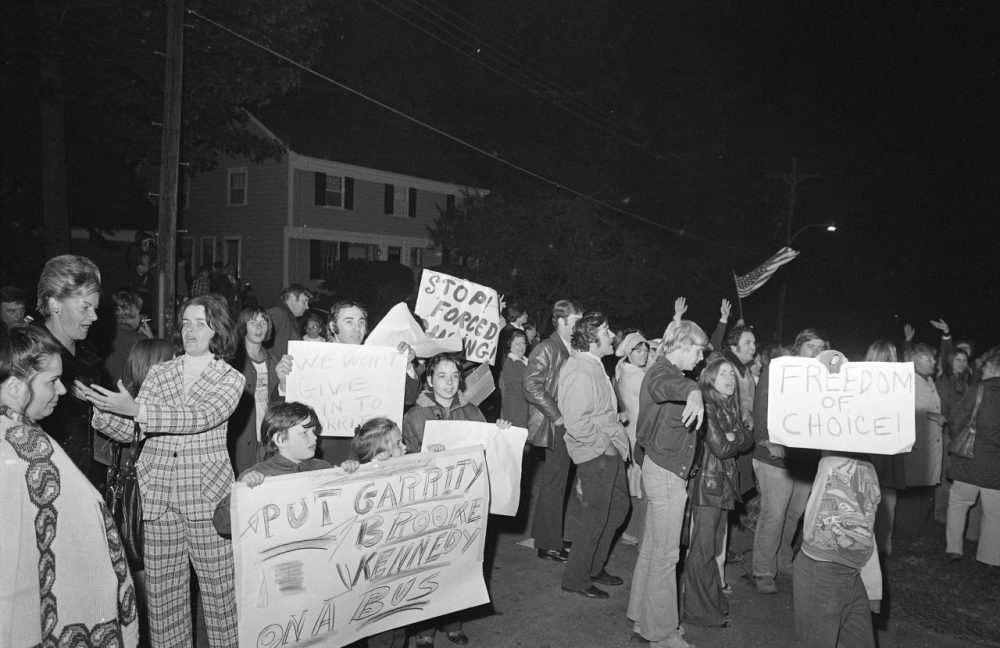

The reaction by some white parents was angry and swift.

Days before busing was to start, hundreds of white students and parents, with the support of the school committee, attended a rally at Government Center. They directed their rage at Sen. Ted Kennedy, a backer of Garrity’s busing plan, as he entered Boston's federal building.

But this was just prelude to what would come three days later, when school started.

Parents jeered as school buses from Roxbury arrived at South Boston High. Black and white students entered through different doors, guarded by police. Of 1,300 black Roxbury students assigned to South Boston, only 100 showed up that day. In Roxbury, just 13 white students from South Boston went to school.

"I was nominally the education person," said former mayoral education aide Schwartz. "But there wasn’t a lot of education to be had during that period of time. It was basically just trying to keep kids from being killed."

Things got worse. Massachusetts State Police and the National Guard were called in. A black student stabbed a white student at South Boston High. An angry mob hauled a black cab driver from his car and brutally beat him.

"I remember riding the buses to protect the kids going up to South Boston High School," McGuire recalled, "and the bricks through the window. Signs hanging off those buildings, 'N***** Go Home.' Pictures of monkeys. The words. The spit. People just felt it was all right to attack children, and yet we prevailed."

In 1981, McGuire became the first black female elected to the Boston School Committee. She’s now executive director of Metco, an organization that provides voluntary busing for Boston black students to schools in the suburbs.

"It isn’t the bus you’re talking about," she said. "You have to be really honest, [it's] not a thing to do with transportation. Everybody in the suburbs rides a bus to get to school, or driving their cars. It isn’t a bus, it’s us. It’s who you live next to. It’s who your kids will marry.

McGuire believes we're better off today with Garrity's decision.

"Absolutely, absolutely," McGuire added. "Part of education isn't just book stuff. It's how to get along as a city and look out for each other. He had to break the mold."

But breaking the mold would not help a broken school system. Critics say simply busing poor kids from one failed school to another could never create a more equal and integrated school system.

Amid the chaos, some 30,000 students, mostly white, left the Boston Public Schools for parochial and private schools.

A decade after his decision, Garrity continued to oversee his plan to desegregate the city's schools.

"Desegregation is not an event, it’s a process," he said. "There’s work that remains to be done, and the challenges of the future I do believe are greater than the challenges of the past."

In 1960, 90 percent of Boston was white. Today, it’s about 50 percent, but now only 13 percent of Boston public school students are white.

"He got the problem right, he got the decision right. It was the remedy that he didn’t get right," historian Vrabel said.

Vrabel says Judge Garrity moved too fast and should have taken more time to address the deeper problems of class — social and educational.

"In attempting to redress the historical wrong of segregation, the court ignored how people live their lives," he said. "Ignored important institutions like neighborhood schools, like a parent's right to send kids to the school of their choice.

"His plan was a failure of public policy," Vrabel added. "The last 40 years we’ve been pursuing a mathematical solution to desegregate the Boston Public Schools, instead of an educational solution to improve them."

Fifteen years ago, the Boston School Committee ended the use of race as a factor in assigning students to schools. Two months later, Garrity died at home in Wellesley. He was 79.

When Garrity died, then-Boston Mayor Tom Menino said, "Whether you agreed or disagreed with his opinion a generation ago, everyone can agree that Judge Garrity's influence on our city will be felt for a long time to come."

Forty years after Garrity's Boston desegregation decision, we can say the same thing.

Correction: An earlier version of this story inaccurately reported that Jean McGuire was the first African-American on the school committee. She was the first black female. We regret the error.

This article was originally published on June 20, 2014.

This segment aired on June 20, 2014.