Advertisement

'They're Still At War When They Come Home': Soldier's Mother Struggles With His Suicide

Resume

Second of two parts. Here's part one.

"I only have a picture now, a frozen piece of time, to (remind) me of how it was when you were here and mine. I see your smiling eyes each morning when I wake. I talk to you and place a kiss upon your lovely face."

For Tammy Sprague Gallagher of Raynham, this has become a daily ritual. She spends a few moments in front of her dresser, which is covered with pictures of her son, Joaquin Pereira Jr., and his military medals. She talks to him, or reads this poem to him.

"How much I miss you being here I really cannot say. The ache is deep inside my heart and never goes away. I need to feel you constantly to get me through the day. I love you so very much. Why did you go away?"

Pereira was 25 when he died by suicide last October.

He was a Massachusetts National Guard soldier and did two tours overseas in war zones. He's one of eight Massachusetts Guard soldiers who've killed themselves since August 2012. That's a big increase in the suicide rate for the Guard, and it happened despite the Guard instituting widespread suicide prevention programs over the last several years.

"He was always a gentleman to me," Gallagher, 51, says of her son, whom she called Jacky. She was the only one he allowed to call him that, she says. Most everyone called him Jack.

"He was a happy kid. Every time he'd walk into a room, the room would just glow with energy. He liked helping people out all the time. He was a good friend. A very good friend," Gallagher says.

She was a single mom — divorced from Jack's father when he was an infant. Always having to work full-time, she says she devoted all of her other time to Jack when he was small.

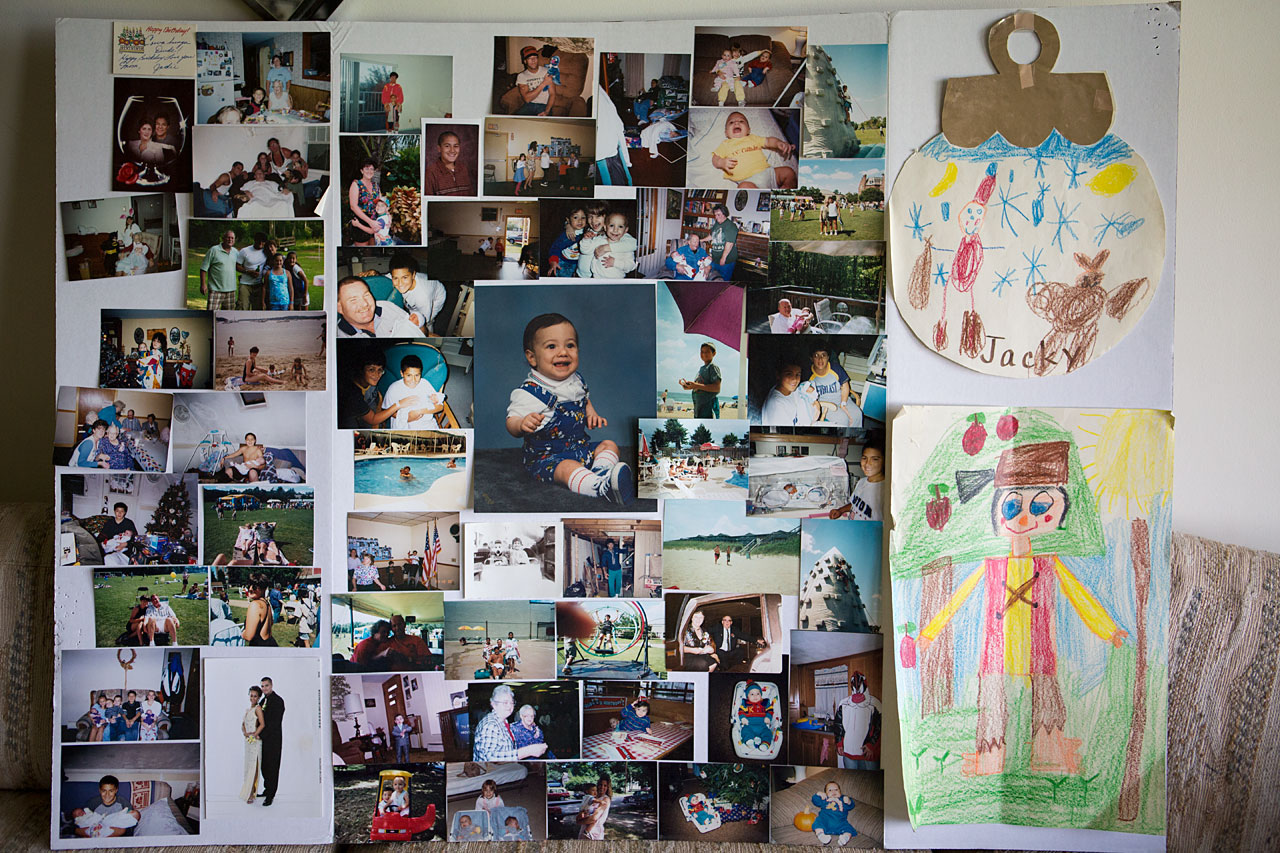

She keeps several huge collages she made for his funeral, with pictures from his life.

"I always dressed up in Halloween costumes alongside of him, too. He's a Ninja Turtle in this one, and then I was the clown," she says, pointing to one of the hundreds of pictures.

"The angels came down and took you. That really wasn't fair. They took my one and only son. My future life, my heir."

An avid sports fan, Pereira played high school football and followed the Bruins religiously. He wanted to join a close friend in the Marines before finishing high school at Bridgewater-Raynham, but his parents made him graduate first. He then signed up for the Army National Guard while also starting college classes, hoping to study criminal justice.

He was about to deploy to Iraq in 2009 when that Marine friend of his, Kevin Preach of Bridgewater, died in an IED blast in Afghanistan. Pereira had to miss the funeral because it came just as he was going overseas. That was something he never got over, his mother says. And, she says, she knows he wanted revenge.

"He really, really wanted to get them back for what they did to his friend," she reflects. "I don't mean to say that, but that's what's in his mind."

Pereira spent a year in Iraq with the 181st Infantry Regiment.

"When he first came home from Iraq, he knew himself he wasn't the same person as when he left," Gallagher recalls. "He was still, you know, the happy guy, and put on a show for everybody at that point. But in his heart, in his mind, had changed drastically."

Gallagher says her son started drinking heavily.

"When he would drink, which he thought was going to make him forget what he went through, it would make it worse for him," she explains. "And he'd be very depressed. He'd cry. I mean, I would call him constantly and talk to him. And he'd reassure me, 'Ma, I'm all right. Don't worry. I'll be fine. I'm a strong guy,' you know?"

She wants other families to know not to believe such statements if a loved one is clearly depressed or traumatized — and to take some sort of immediate action to protect the person.

Gallagher tried to get her son to talk, but whenever he started, he immediately stopped, she says — never revealing what he had experienced in Iraq. She urged him to talk with a psychologist. But, she says, Jack told her he couldn't seek help.

"He goes, 'My job's not done. If I go to a psychologist, they're not going to allow me to go to my other missions that I want to do' ... He wanted go to Afghanistan next. He goes, 'And if I let them know, I'm not going anywhere,' " she recounts.

Leaders of the Guard's suicide prevention programs say that's a common fear among soldiers — that revealing depression or other mental health issues will affect their standing in the military. Commanders tell soldiers it's a sign of strength to get help, and they can't be strong for their comrades if they're not at peace mentally.

Just eight months after Pereira returned from Iraq, he deployed to Afghanistan for more than a year — this time with a military police unit.

Later, he and other soldiers stood guard at the bloody scene of the Boston Marathon bombings, where he stayed for two weeks. He never opened up about that experience, either, his mother says. But it added to his being on edge. He had been getting startled by noises out on the street and at home.

She, meanwhile, felt helpless — a feeling that persists to this day and pours out in the thoughts her niece helped put into words.

"You should have so many years to watch your family unfold. And in the midst of all, watch me, your mum, grow old."

As for help from the military, Gallagher says she knows Jack got a packet of information on where he could seek services including medical and mental health care. But he never opened it. She received letters on how to look for signs of post traumatic stress and other problems in her soldier son.

"But, see, my son was a good actor. He was hiding stuff," she says. "They need to make sure that they go through some kind of rehabilitation process, or whatever, when they come home after serving. They need to pass screenings or something."

The Guard says members are required to go through an in-person evaluation at a Veterans Affairs hospital within 90 days of returning from deployment. And they also have to pass an annual health and mental health check-up. But Guard leaders acknowledge it's easy for some people to say they're fine when they're not.

Pereira even promised his mother he wouldn't kill himself. That was in September of last year, when his stepbrother on his father's side died by suicide.

"I had said to him, 'Jack, don't ever do this to your family,' " Gallagher recounts.

"'Mom, I would never do this to my family. I couldn't even do it to myself.' That's what he told me," Gallagher explains. "And he made me feel, 'OK, I'll never think about that again, because he's not going to do that.' "

But just three weeks later, he did.

After Pereira spent a weekend hanging out and partying with friends, during which he started drinking again, those friends called his mother saying they couldn't find him. His mother says she knew in her heart he was gone because he didn't respond to her messages as he always did. He was found dead on his father's property.

"What is in his mind is what made him do this. It was ghosts haunting his mind, and he could not get rid of it," Gallagher says. "They're still at war when they come home, these soldiers are. In their minds they are."

Only after his death did Gallagher come to learn just a little bit of what her son witnessed and experienced in war. A Guard leader was the one to tell her Jack had survived an IED blast.

"And it had flipped over his Hummer multiple times, and he was actually taking his soldier buddies, rescuing them, taking them out of the Hummer, because the Hummer was on fire," she says. "And he's also got his gun, shooting, fighting at the same time. I felt so proud of my son — how brave he must have been to get through something like that."

Now, Gallagher says, her days are consumed with thoughts of Jack — to the point where she feels her brain is too full to hold anything else.

But she still has family to care for. She says her daughters, 14-year-old twins, went through times of nightmares, in which they woke up crying for their brother. Gallagher's husband — Jack's stepfather but very much a second father figure — also still breaks down at times.

She tries to find moments of peace, when she thinks of her pride in her son and all the good years they had.

"Now let's start this day together hand-in-hand. Have our cup of coffee and see what it has planned. I hope you're watching from above at the daily tasks I do. And let there be no doubt at all, I really do love you."

Resources: Here's a document of suicide prevention resources from the Massachusetts National Guard. You can reach the Massachusetts National Guard suicide hotline at 1-855-620-ASAP (2727), and the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

This segment aired on September 19, 2014.