Advertisement

As Winter Electricity Prices Jump, Mass. Debate Over Natural Gas Pipelines Heats Up

Resume

First in a two-part series. Here's Part 2.

If you're shocked by your current electric bill, you're not alone.

In the coming weeks, Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker is planning to host fellow New England governors for an energy summit. Topic one for the Boston gathering will be the soaring cost of electricity.

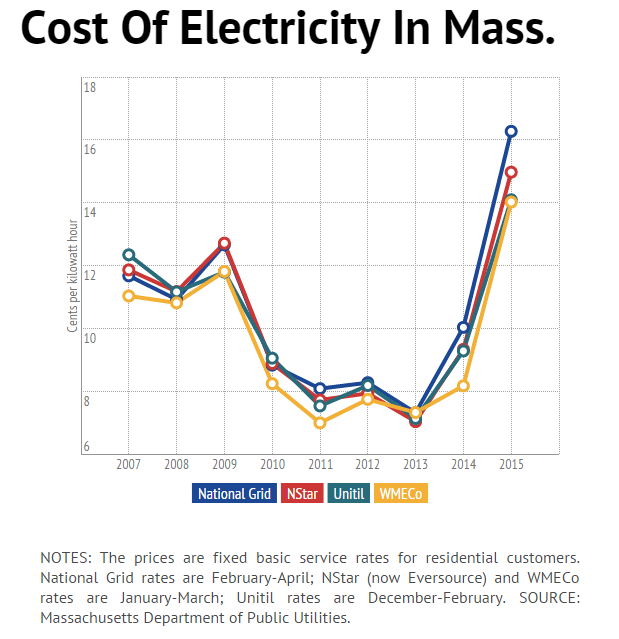

For many ratepayers, bills have gone up as much as 40 percent this winter. And that's on top of what are typically some of the highest electricity rates in North America.

And yet, the wholesale price for natural gas — the energy source used to generate most of the electricity in the region — is actually lower this year.

Baker thinks he knows why: "Our big problem here is we don't have enough pipeline capacity," he said recently.

Pipeline supporters say the solution is simple: Build new capacity and prices will drop dramatically.

But pipeline opponents charge there are cheaper and cleaner alternatives.

The Rise Of Natural Gas In Mass.

Half the households in Massachusetts use natural gas for cooking, heating and hot water.

Our natural gas delivery system, mostly out of sight and usually out of mind, is a vast network of pipelines — some as big as 3 feet in diameter, carrying natural gas at up to 1,500 pounds of pressure per square inch.

That's a lot of pressure because we're at the end of the line.

There are no gas fields in New England, so we import all that we use. Eighty percent is transported through five long-distance pipelines. Some comes from Canada, most from southern states.

Demand for natural gas is highest when the weather is coldest. One day last month, demand in the Northeast was the highest in recorded history.

Gas generates a lot of heat in Massachusetts, and increasingly it's being used in the region to shed light as well. The pipelines that carry natural gas for heating are the very same ones that transport it to utilities that burn the gas to generate electricity. But the electric companies have to stand in line behind heating companies, which get first dibs on pipeline capacity.

"When we hit one of those cold days the demand on the gas heating side is eaten up to serve those customers," said Anne George, vice president of public affairs with ISO New England, the region's electric grid operator. "And there's very little left on the pipeline for the electric generation needs, and what we've said is additional capacity is needed to bring in additional natural gas to the region."

It's ISO New England's responsibility to oversee the electric grid's reliability, but these days it's also overseeing an energy revolution — a transformation in the way the region's electricity is produced.

In 1990 just 5 percent of New England's electricity was generated by natural gas. Today, the portion has increased 10-fold.

"We've seen this shift go from coal and oil to really dominated by the natural gas electric generation," George said. "Over 50 percent of our electricity is generated from natural gas-fueled resources, and so it's a very important fuel for providing electricity to the region."

And very soon, natural gas is going to get even more important. Brayton Point — the last coal power plant in Massachusetts, and one of the largest electric generators in the region — is set to close in two years, and another major electric generator, the old Salem Harbor plant, is being converted from coal burners to gas turbines.

George says that's going to put even more pressure on existing pipelines.

"So the oil and coal is retiring," she said. "It needs to be replaced, and the most likely replacement is natural gas and maybe some renewables."

"Maybe some renewables," as she put it, because fossil free energy sources have a tough time competing with natural gas in New England.

Large-scale offshore wind is still a long way off. And while solar is getting a lot cheaper, it's not cost competitive compared to a new source of natural gas.

In Pennsylvania and Appalachia lies the vast Marcellus Shale gas play, where natural gas, locked in rock, is released using a relatively new mining method: hydraulic fracturing, or fracking.

"Without Marcellus Shale the price of natural gas in the commonwealth of Massachusetts and throughout the Northeast would be perhaps two, even three times higher than it is right now," said Tom Kiley, president of the Northeast Gas Association, a trade group the promotes natural gas.

Even so, because there's not enough space in our pipelines, there were brief periods last year when the price for electricity generated by natural gas in New England was the highest on the planet.

And Kiley predicts the problem is going to get worse.

"The local gas distribution companies are going to grow," he said. "They have been converting a lot of customers from other fuels to natural gas. There's a huge demand because of the price advantages of natural gas over other fuels, so we need more pipeline to bring those volumes to serve customers."

The question then becomes, how much pipeline?

"That's the big question," Kiley said. "It depends on who you ask."

Ask Allen Fore and he'll tell you we need a lot more pipeline. He's a spokesman for Texas-based Kinder Morgan, one of four companies interested in building new gas pipeline through Massachusetts, and the largest company of its kind in the country.

"We're a pipeline, we just transport," Fore said. "And we're transporting on the interest and needs of our customers. If they're telling us they need this size pipe, this much gas, we're going to find a way to get it here."

A dozen local distribution companies told Kinder Morgan if it found a way to get the gas to them, they'd sign 15- to 20-year contracts. Without those promises federal regulators won't permit pipeline construction.

Kinder Morgan proposed building a 127-mile pipeline stretching across the northern tier of Massachusetts. Carrying Marcellus Shale gas, it would have increased the amount we now import by half and provided good jobs with good pay with benefits for union construction workers.

"I could travel to western Mass., start from the beginning, and travel all the way to Dracut," said one of those workers, Jared Jalbert, from Winchendon. "I could be employed for as long as it's in progress."

According to Kinder Morgan, construction would last two years and mean 3,000 jobs, but when finished, the pipeline would employ only about a dozen people to operate.

Pipeline Galvanizes Grassroots Opposition

In each town along the proposed route — 45 Massachusetts communities in all — spokesman Fore and Kinder Morgan executives met with local residents and officials to try and build support for their plan.

Despite the prospect of cheaper gas and new revenue from corporate property taxes, Kinder Morgan found the pipeline a tough sell to people like Fitchburg state Rep. Stephen DiNatale.

"I'm torn, I want to learn more," he said at a 2014 public meeting. "I don't have any assurances from Kinder Morgan that gas is going to remain in the U.S. Are my ratepayers going to see any reduction in what they're paying? No. And who's going to pay for the cost of the construction of the pipeline?"

Fore says Kinder Morgan has no plans to use the pipeline to export gas overseas. And it's no longer asking consumers to pay the $5 billion upfront construction cost. But environmentalists dug in.

"Where they're planning to build the pipeline is through small towns, through heritage farms and conservation land, and it leaves a 50-foot-wide permanent gash through the landscape," said Rosemary Wessel, co-founder of the opposition group No Fracked Gas in Mass.

Late last year, in a surprise move, Kinder Morgan announced it was dramatically altering the proposed route. Instead of building all of the pipeline in Massachusetts, half would be in New Hampshire, and 90 percent would run along existing utility rights of way.

Fore says Kinder Morgan got the message.

"Companies that are proposing major infrastructure that are going to have impacts should listen, and not just with window dressing, they should respond," he said.

But it was too late. Every community along the originally proposed route passed a resolution banning the company's surveyors from their lands.

The proposed pipeline had galvanized a statewide grassroots rebellion — environmentalists joining forces with property rights activists, people who didn't want the pipeline in their backyard, their front yard or any yard.

Last summer, pipeline foes marched the entire proposed 127-mile route across the state, ending in Boston. On Beacon Hill, opponents found a receptive audience with then-Gov. Deval Patrick, as he and his advisers met with the demonstrators.

"The governor has said very publicly that he's very skeptical of the project," said Mark Sylvia, who was energy undersecretary in the Patrick administration.

Two of Patrick's proudest achievements were passage of the Global Warming Solutions Act, which phases in deep, mandatory cuts in fossil fuel emissions, and efforts that made Massachusetts the most energy efficient state in the nation four years in a row.

"On an annual basis the amount of electricity we consume as a state has been flat, and that is because of the energy efficiency programs," Sylvia said. "So do we need more electricity in the future? Well, what we need is cleaner resources, and we need to ensure the electricity we do use is reliable. And so we have to ask some very tough questions."

To get answers Patrick commissioned an independent study to determine if Massachusetts really needed more natural gas and, if so, how much. The results came out the last day of his administration, and the first of Gov. Charlie Baker's administration.

The study found Massachusetts needs about half the pipeline capacity Kinder Morgan wants to build, but it also concluded that burning more natural gas would make it highly unlikely the state could meet its legally required greenhouse gas targets.

"We're in a very difficult situation," said Mathew Beaton, Baker's energy secretary. "We want to continue to make Massachusetts a leader in energy efficiency and renewable installations and very much intend to do so. However, we need to address the realities of the overall demand for electricity and how are we going to meet those demands."

Supporters say gas pipelines provide a bridge to a clean energy future. Opponents say it's a bridge too far that locks the region into a fossil fuel future.

This segment aired on March 10, 2015.