Advertisement

Remembering The Armenian Genocide 100 Years Ago Holds Special Significance In Watertown

Resume

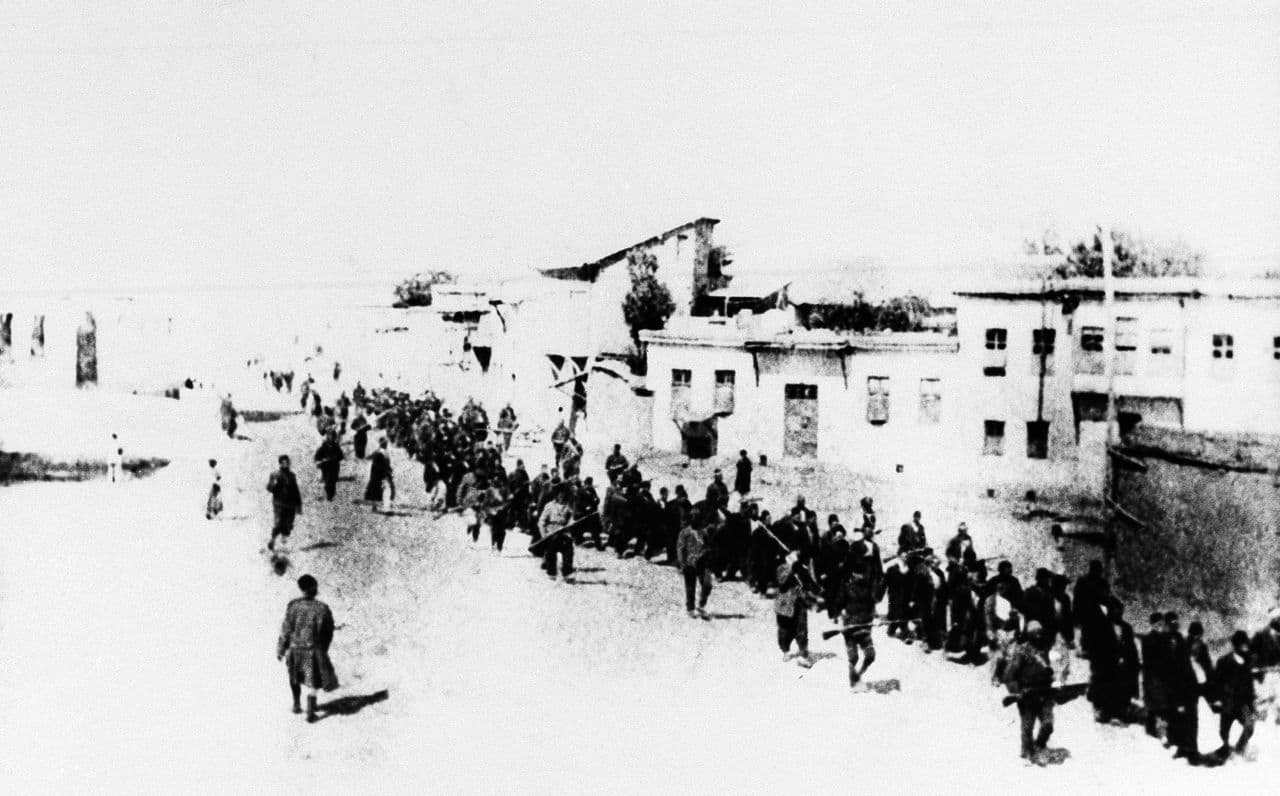

Armenians around the world today commemorate the 100th anniversary of the genocide.

It was April 24, 1915, when thousands of Armenian leaders and intellectuals in Constantinople were deported and executed. An estimated 1.5 million Armenians died over the next seven years through the final days of the Ottoman Empire and a brutal civil war.

Watertown Connection

Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day has special significance in Watertown. The Boston suburb is home to many descendants of survivors of the genocide. The third largest Armenian community in the United States is in Watertown, where between 7,000 and 8,000 Armenians account for about a quarter of the city's population.

Worcester was the first Armenian settlement in the U.S., but it's Watertown where Armenians thrived.

The Hood Rubber Co., the largest rubber shoe factory in the world, was founded at the turn of the 20th century and located at what is now Watertown Mall. Armenians, along with Italians, Syrians and Greeks, turned out rubber soles by the millions, with samples tested by local kids.

In the documentary "Destination Watertown," Rose Magarian recalls volunteering to put the shoes through their paces.

"I was the best test girl," she said. "I got a new pair of sneakers every week because I worked so hard, because my mother had me running all day."

A lifelong Watertown resident, Magarian died three years ago. Her memorial service was held at St. James Armenian Church, one of three Armenian churches in Watertown.

'Little Armenia'

Parishioner Sandy Raphalian calls St. James the heart and soul of her community.

"We have a full house tonight. It's wonderful," she says. "Everybody comes, everybody comes."

Once a month, Armenian-Americans from Watertown, Newton, Belmont, Lexington and beyond gather at St. James for fellowship, traditional music and food. The gatherings counterbalance the forces of assimilation.

"We love America, this is our home as well, but there are lots of challenges," said Father Arakel Aljalian, the pastor at St. James.

"The church, they try to keep the ethnicity of the Armenians," he said. "So they would practice their faith, practice their culture, their traditions, their heritage. So Watertown, we call it 'Little Armenia.'

"You know you go to, whether it's the local banks, you to Armenian stores, they all speak Armenian, and it's a unique place, Watertown," he said.

Scars Remain

Near where the Hood Rubber Factory once stood, there is East Watertown. It's filled with stores that cater to the tastes of Armenians. Customers and shopkeepers three generations removed still share memories and scars of the genocide.

Sarkis Ourfalian and his brother own Massis Bakery, and like the other stores in this part of Watertown, it will be closed Friday in remembrance.

"My grandmother had two kids, this is during the genocide [in] 1915," he said. "One of them was 5 years old, a boy, and a 2-year-old girl."

Ourfalian's grandmother was forced to flee the land her family lived on for centuries. Her 2-year-old daughter couldn't make the arduous journey to Lebanon, so the infant was left at a church. Ourfalian says mother and daughter were never reunited. Turks burned the church down.

"So there were no survivors," Ourfalian said. "So throughout her life she always wear black. Just imagine you have two kids, and you have to leave one of them behind. And then realize what kind of decision you've made, that she couldn't live with."

A Word For The Suffering

Armenians originally called it the "Great Crime," or "Massive Catastrophe." There wasn't a word to describe the deliberate destruction of an ethnic group until after World War II.

The term "genocide" was created and adopted by the United Nations. It's a legal definition, and Turkey and most nations, including the U.S., refuse to apply the word "genocide" to what took place 100 years ago in the Ottoman Empire.

"Turkey understands and respectfully recognizes the Armenians' sufferings," said Omur Budak, who is consul general of Turkey in Boston. "We share the sufferings."

Thirty years ago, Armenian anger toward Turkey turned to rage, and rage to terror. During this time, the-then honorary consul general to New England was assassinated in Somerville, his killer never caught.

Budak hopes for reconciliation.

"Now, we need to heal the wounds of the past century. Turkey is determined to this goal based on just memory and a peaceful common future," he said.

In 2009, Turkey and Armenia signed a protocol to normalize relations and exchange diplomats, but domestic politics on both sides derailed the agreement.

'How Do You Keep A Culture Alive?'

The wounds of the massacres run deep in the diaspora, but in Watertown, Armenians and their descendants would embrace their new national identity. For many the language was lost, and over time, those who remained in Armenia developed a different dialect and different traditions evolved. The distance between homeland and new home grew further apart.

Still, the toll of genocide is measured not just in lives, but generations.

"That means whatever is left behind from their history, from their culture is foreign to them. I mean it's a difficult question, 'How do you keep a culture alive?' " asked Berj Chekijian, director of the Armenian Museum of America, located in Watertown.

"People were throwing away Armenian books, because they couldn't read it," he said. "Their parents had brought it over from old country, and they put a sign in the newspapers, Armenian newspapers here, that 'We are collecting Armenian books.' And people starting bringing Armenian books."

People then said they had other things, and from this modest beginning in a basement in the 1970s, the collection has become the largest Armenian museum in the U.S. It's rich in artifacts dating back more than 5,000 years.

But it's what happened 100 years ago the draws Armenian-Americans together today.

"The genocide, the recognition of the Armenian Genocide in this world has become a unifying force and keeps us as a community strong," Chekijian said.

Survivors and their descendants from Rwanda, Bosnia, Chechnya, Cambodia and more will gather at the Massachusetts State House Friday, and from there, together, they'll march to the Armenian Heritage Park on the Rose Kennedy Greenway.

This segment aired on April 24, 2015.