Advertisement

How One Man In N.H. Spent 575 Days In Jail For Trespassing

Resume

Michael Treadwell sat at the back of a courtroom. In a windbreaker and khaki pants, he leaned over his work boots, elbows on his knees. At first, I thought he was chewing gum — a bold choice in a courtroom. When we began to talk, I discovered it wasn't gum Michael was chewing. It was his own gums. Michael doesn't have any teeth.

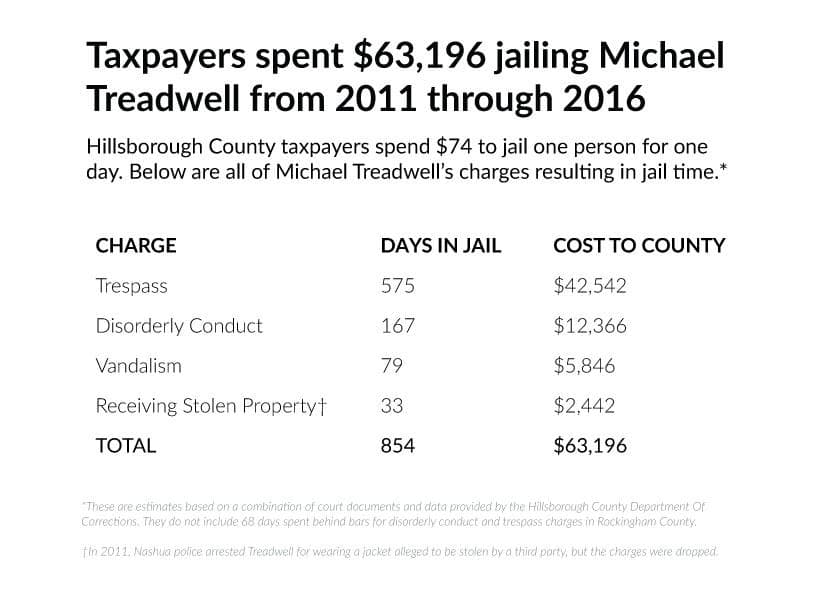

I had been looking for Michael, 53, since I came across his criminal record. I was reporting on the way poor people are jailed for minor crimes because they can’t afford bail. Michael, I discovered, had spent a total of 854 days in jail over the last six years. His charges all come from some combination of being homeless and getting drunk. In those six years, the county had spent over $63,000 locking him up. I wanted to know how a man can spend so much time in jail for such minor offenses.

I watched Michael plead guilty to a charge of public urination. Then, we walked in the rain through the city.

"When you live in a town like Nashua, there’s not a lot of homelessness there," he told me. "It kind of like puts you in the spotlight, especially if you drink alcohol and stuff."

There are many forces shaping how people end up in jail. Substance abuse, mental health issues and economics are all at play. Michael's story shows us when people like him don't get the help they need, taxpayers can end up with a hefty bill.

Here's a random sample of his criminal record, from a few months in the summer of 2015: Trespass in an apartment building; spend 30 days in jail. Bother customers at a restaurant; spend 42 days in jail. Panhandle aggressively; spend 30 days in jail. There are charges for drinking in public; loitering; and urinating on buildings, all in just a few months. For years, this cycle from the streets to court to jail repeats and repeats.

Still, to Michael, jail is no worse than the streets. "People kill homeless people, violence and everything else. It can be a very dangerous life to live in," Michael said, adding "I don’t suggest jail as an alternative."

Since 2011, Michael’s most serious convictions are two acts of vandalism. Once, according to police, he damaged a truck bumper with a piece of wood. Another time, he pulled a rain spout off a police building. For that, he spent six months in jail.

Mostly, Michael gets arrested and then jailed for trespassing. Combined, he’s spent more than a year and a half in jail on that charge alone.

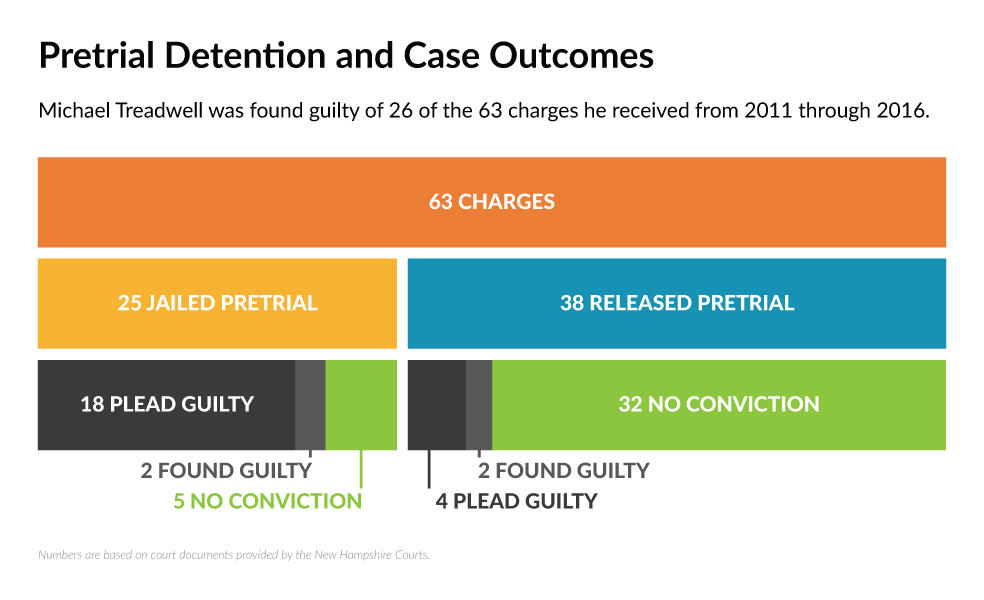

More than half of his charges end up getting dropped — but often not until he’s spent days or weeks behind bars.

Michael did time for drug charges in the early 1990s, but after that he stayed on the right side of the law for nearly two decades. He worked as a trucker, and said he longs to drive trucks again. He had two teenage daughters, and got married. His ex-wife, Sherri Treadwell, still speaks of him tenderly. Although they divorced in 2007, Sherri pays Michael’s cellphone bill, and coordinates meetings between him and his daughters. Sometimes, she said, he shows up drunk.

According to Sherri, the drinking, the homelessness and arrests are all symptoms of something bigger: his mental illness.

A year or so into their marriage, Sherri said, Michael started to change. He thought people were listening in on his conversations, bugging the telephone. "He would whisper to me in the car 'Shh, the car is bugged!' No, the car is not bugged. He wouldn't talk on the phone. [He thought] people were following him" Sherri said. Michael turned to alcohol to cope, and eventually, Sherri asked him to leave.

Michael hasn’t been without help.

A year after his divorce, Michael found Jarretta Copeland and adopted her, unwitting, as a guardian of sorts. He showed up at her church asking for bus money, and nine years later, Copeland calls looking after Michael a "God-given mission." She knows him better than anyone now and has seen him at his worst.

"He gets to yelling and screaming and hollering. And he's talking and he's cussing people out," Copeland said. "It scares people because they don't know if he's going to attack them, they don't know what his intentions are."

Copeland said Michael needs to be admitted somewhere that can address his drinking and the voices in his head, at the same time. Really, she said, he needed this decades ago.

She’s tried to get him into the state mental hospital. Three years ago she thought the moment had finally come. A judge ordered that he be taken to be evaluated for involuntary commitment. The jail had Michael ready to go, and the hospital had a psychiatrist available. But the sheriff never got the memo. He was supposed to take Michael from the jail to the hospital.

By the time the sheriff finally did take Michael to the hospital, Copeland said, the psychiatrist had left. Copeland says the jail wouldn’t coordinate another visit.

Instead, Michael continues to cycle from the streets to courthouses to jail cells and back again.

He’s not the only one. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 64 percent of jail inmates nationwide have mental health problems. Seventy-six percent of those inmates also abuse drugs or alcohol.

New Hampshire in particular has an abysmal track record when it comes to mental health. Four years after a lawsuit and a $30 million settlement, there is still a month-long waiting list at the state mental hospital.

At one point, Sherri told me if Michael gets on the straight and narrow, she’ll remarry him. But then, later, she told me this:

His liver is gone now because of the alcoholism, so we know he’s not going to be around for too much longer. And this hurts the girls and I. And it hurts me more, because I know the system could have done something. Had he had some kind of money or clout or whatever it takes, he could have gotten that help that he needed.

The last time I talked to Michael, he told me he wanted to go down to South Carolina, where he grew up, in order to get his trucking license back in order. I recently checked in with Sherri. And she told me, he had gotten to South Carolina. He'd called her from a jail there.

This story is a production of the New England News Collaborative. It was published first by New Hampshire Public Radio.

This segment aired on March 6, 2017.