Advertisement

As Fentanyl Deaths Rise, An Off-Label Tool Becomes A Test For The Killer Opioid

Resume

Jess Tilley pushes aside magazines on a waiting room table and lines up three used "cookers" — small aluminum caps in which someone mixed and heated up their drugs. She mixes water with drug residue at the bottom of each cap. The demonstration is ready.

Tilley pulls a handful of green plastic pouches out of a shoulder bag and rips the top off of one of them. She slides a thin, flexible wand out of the pouch. It's a rapid test for fentanyl, the powerful opioid blamed for rising overdose deaths in Massachusetts and many other states.

This thin strip of plastic is the newest tool in the fight to curb opioid overdoses and deaths, but its value is largely untested. That's because the strip is designed to detect fentanyl in urine.

But Tilley and a small but growing group of overdose prevention workers around the country are teaching users to dip the strip into drug samples before they use. The idea: If drug users know they're about to inject, snort, smoke or swallow fentanyl, they'll take smaller doses, avoid using alone, and make sure they have naloxone handy in case they overdose.

"People who would have done five bags [of dope] are cutting back to one-and-a-half or two. People who would pop four pills are only doing one," Tilley says. "We’re getting amazing feedback from users, like, 'This has saved me.' "

Tilley collects donations to purchase the strips. She's distributed more than 2,400 in less than a year through a group of current and former drug users she founded called the New England Drug Users Union.

On this day she's in Holyoke to show staff at the Tapestry Syringe Access Program how the strips work. Four women stare as Tilley dips a strip into one of the used cookers and lets it soak for 15 seconds. She lays it across the top of a cooker to dry, and moves down the line, testing each one.

These women have seen the damage fentanyl can do, but they've never seen a rapid test they could share with clients. They lean in as dark pink lines emerge, one on each strip. A single line means the drug has fentanyl. Two lines is a negative test result.

At first, it looks like all three cookers and the two bags show traces of fentanyl. There could be a lot or a little; the test doesn't measure the amount of fentanyl, just its presence. Then, on one strip, a faint second line emerges.

"It's so faint," says needle exchange employee Emily Moulton.

"Something like this, I'd definitely tell someone to test again," says Tilley.

That's if the user can get his or her hands on another strip. Tilley has 15 left in her bag at the moment and no money to buy more for a few weeks. There are also no formal guidelines about when to test again and nothing on how to use these strips to test drugs this way.

Tilley trades tips and experiences with other overdose prevention workers around the country. But many who work with drug users are hesitant to recommend or hand out the strips. Here’s why.

'Don’t Know What The Results Mean'

The strips are designed to pick up six legal forms of fentanyl — those prescribed by doctors. The varieties of illegal fentanyl that are mixed into bags of heroin, cocaine or other drugs are largely cooked up in illicit labs that tweak the recipes. Do the strips detect all these different variations of fentanyl? No one knows.

Vancouver's Insite clinic, which supervises users while they inject drugs, started offering the strips to clients last year. But Dr. Mark Lysyshyn, who directs opioid response for Vancouver Coastal Health, says the test strips are only available in the clinic, where a user can be revived if the test result is wrong.

"We were concerned that if we offered the test in the community and somebody got a negative drug check, they might think their drug is safe, but actually, we don’t know what the results mean," Lysyshyn says.

A negative result could be an error, which the manufacturer says happens less than 1 percent of the time, or it could mean the test failed to detect a new variety of fentanyl.

BTNX, the Canadian company that makes the strips, agrees with Lysyshyn; they should only be used in a medical facility where someone who overdoses could be revived.

“You don’t want to put this out on the street where [drug users] think it’s negative, and therefore, it’s OK for them to inject themselves, and then they find there might be something else and they’ve overdosed,” says BTNX CEO Iqbal Sunderani.

Sunderani says he’d be willing to test the strips to see if they detect additional fentanyl analogs, such as carfentanyl, if someone funded the research and provided samples.

But as more and more deaths are blamed on fentanyl, interest in the strips is spreading. BTNX says it sold 42,000 strips in Canada and the U.S. in the last six months. St. Ann's Corner of Harm Reduction, a needle exchange program in the Bronx, says it's the first U.S. program to distribute fentanyl test strips. Organizers say they tell clients the test is not always right but that it is worth doing.

"It's our obligation," says Van Asher, data manager at St. Ann's. "If the strips can detect some analogs of fentanyl, and we can make them available, and that may reduce one death, I think they will have paid for themselves many times over."

"If the strips can detect some analogs of fentanyl, and we can make them available, and that may reduce one death, I think they will have paid for themselves many times over."

Van Asher, data manager at St. Ann's Corner of Harm Reduction

The strips, at $1 apiece, are not expensive, but some overdose prevention workers say they need science to support the value of the purchase. A handful of epidemiologists are stepping in.

Brandon Marshall, an assistant professor of epidemiology at Brown University, is working with colleagues in Boston on a pilot project, asking 40 young drug users to test for fentanyl in their urine. He hopes to study pre-use drug tests using the strips later on. Marshall says he wants to find out if drug users change how much they inject or are more likely to use near someone who could call 911 if they know they are taking fentanyl.

"We’re dealing with a fentanyl overdose crisis at the moment in Massachusetts and Rhode Island and other states across the nation," Marshall says. "So this is one technology that needs to be understood and explored -- and, if it’s found to be effective at reducing overdose risk, broadly promoted."

Boston-based epidemiologist Michael Gilbert is working on a consistent protocol for use of the strips: how long to leave them in the liquid, how long to wait for a clear result, etc. But Gilbert says drug users also need more ways to test the products they buy.

"Ideally they'd be accessible through drop-in clinics," Gilbert says. "People would be able to submit a sample, have it tested, and walk out with their results."

Gilbert says until those services are available, the strips are the best option for active and casual drug users.

The few physicians in Massachusetts who know about the strips are not recommending their use, although Dr. Ed Boyer, an emergency room physician at Brigham and Women's Hospital, says he understands the impulse to use them.

"It's not misguided to try and stay alive," Boyer says.

Boyer does worry the tests will never be up to date, and thus effective, because dealers will keep adjusting their drugs, looking for a bigger "bang for the buck."

"If people stop buying a product because it has fentanyl," Boyer says, "dealers may just switch to another chemical that can't be detected by these strips.

Despite Unknowns, Case For Trying New Ways To Save Lives

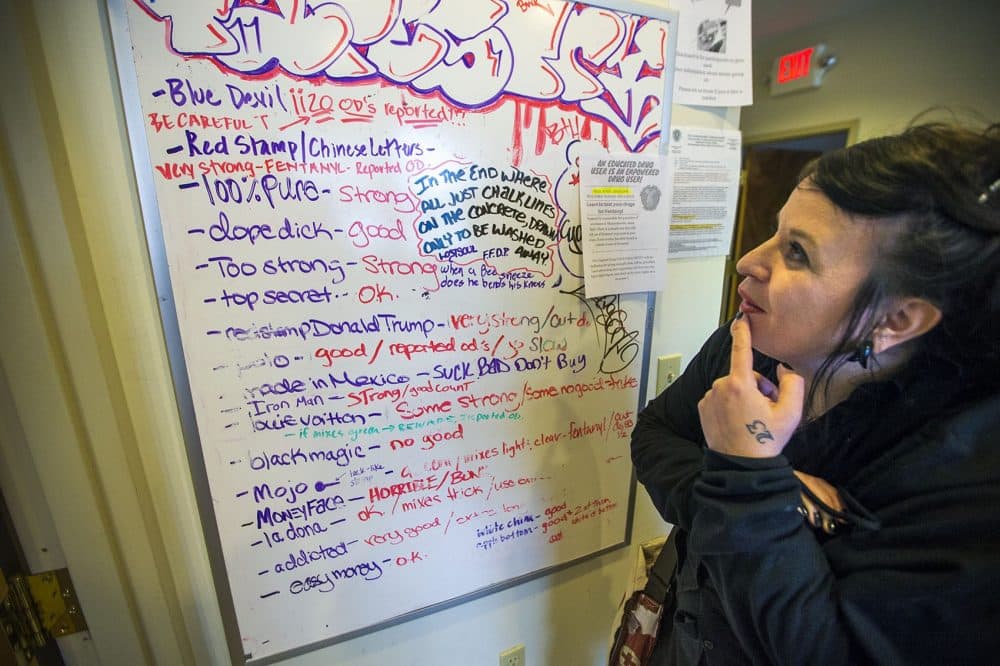

Tilley describes a different experience with dealers near her home base of Northampton. She says a half dozen of them are using the strips to test their drugs. If the test comes back positive, they're adding more elements to thin the mix and warning customers.

As the training winds down at the needle exchange in Holyoke, staff say they hope to start distributing the strips right away.

"It's time to try new approaches to prevent death and keep people alive," says Liz Whynott, director of HIV health and prevention at Tapestry.

"They should be available at the dollar store," says Lissette Saillant, a needle exchange staffer. "Just a dollar, and you can save a life."

These women will proceed carefully — making sure they educate users about the risks of using the strips — and to avoid arrest themselves. Just being present with heroin and other such drugs is a crime.

"I don't think that's anything we'd want to see right on Main Street," says Det. Lt. Alan Borowski, who oversees investigation for the Northampton Police Department.

These strips create another possible merger or collision point for law enforcement and public health.

"We as an agency have tried to get people the help they need," Borowski says, "but it's a very tricky subject in the whole fight against the drug problems that we face every day."

Police say for now it would be up to individual officers to decide whether to charge the person training drug users to check the contents of their drugs.

This segment aired on May 11, 2017.