Advertisement

JFK 100

Decades After His Graduation, John F. Kennedy Is Being Rediscovered At Harvard

Resume

Part of a series marking the 100-year anniversary of the birth of President John F. Kennedy in Brookline.

A century after his birth, discoveries about John F. Kennedy are still being made — and they're being made at Harvard.

This month the university released the oldest known recording of Kennedy's voice.

The recording was created when Kennedy was 20 years old and features his characteristic Boston accent. The scratchy 1937 artifact had been made on an aluminum disk in a public speaking course that Kennedy, like all Harvard undergraduates, had to take. It's part of an exhibit at the Harvard Archives on the ties between the university and its illustrious alumnus.

The recording is believed to have been made in Holden Chapel, where Kennedy, a sophomore, took the public speaking course. Sitting in the 18th century chapel 80 years later, Harvard archivist Megan Sniffin-Marinoff says beginning in the 1920s, Kennedy's professor would record each student's voice twice during their Harvard College career.

"Every student had to do this in that time period, and that's actually one of the reasons why we have John Kennedy's voice," Sniffin-Marinoff says.

Harvard archivists were nervous when they first listened to the restored recording.

"We hoped it wasn't just reciting 'Mary had a little lamb,' but something a little bit more substantive than that, and it did turn out to be that," Sniffin-Marinoff says. "He was speaking to an important public issue of the day, which was the appointment by FDR of Hugo Black to the Supreme Court, and one of the things that we really did notice when we were listening to the tape is that he was very energetic."

Sniffin-Marinoff believes the instructors coached Kennedy in thinking about public presentation, imagining himself speaking on the radio. The course was, in part, to prepare people for broadcasting.

"We all know the circumstances surrounding Mr. Black's appointment to the Supreme Court. Whether Mr. Black's appointment to the court is a correct one is hard to say," Kennedy says in the recording. The appointment had became controversial after it was revealed that Black had ties to the Ku Klux Klan.

"It was amazing because for me, immediately it was recognizable as John Kennedy," says David Ackerman, the Harvard Library's head of media preservation services. Ackerman was probably the first person to hear the recording in 80 years.

"I immediately latched onto it," Ackerman says. "I knew that it was him, and that was just so cool to hear that and then know, oh, yep, this is him."

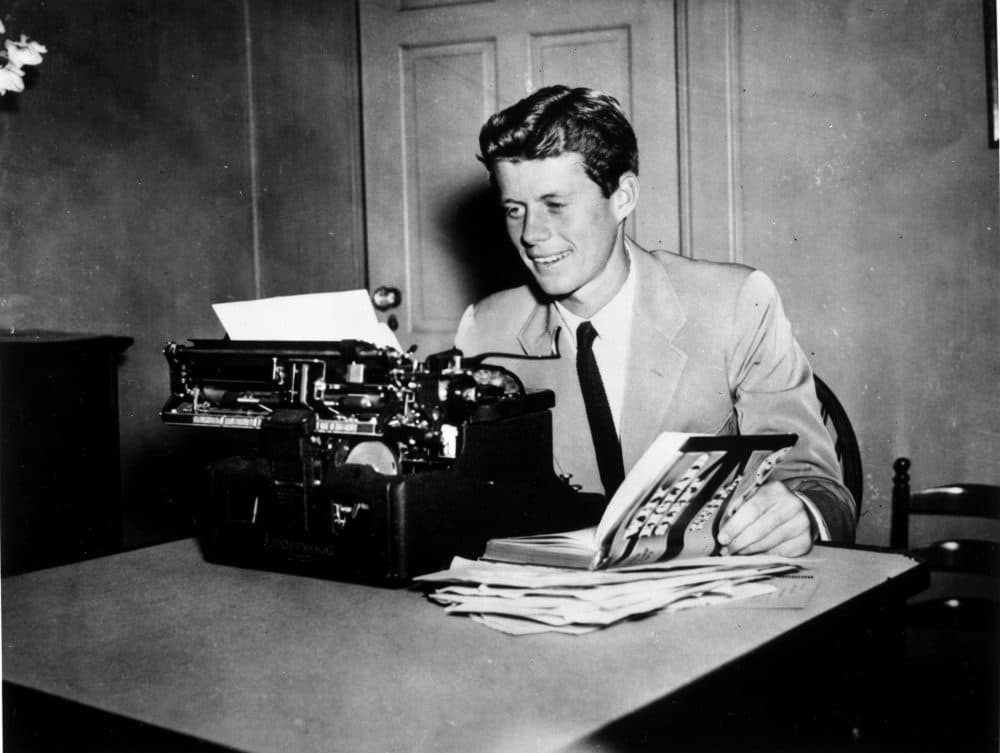

Someone else at Harvard is making discoveries about Kennedy. Four years ago, Fredrik Logevall won the Pulitzer Prize for his history of Vietnam, "Embers of War." Logevall, at the Kennedy School of Government, is now focusing his attention on Kennedy — and he is discovering someone beyond the popular perception of him as a playboy or someone whose father's money, influence and connections helped him get ahead.

"I think there's no doubt that Joe Kennedy's influence is important, and that's something I'll develop, but I also want to suggest that from an early age, indeed from his Harvard days even, you see a serious thinker." Logevall says.

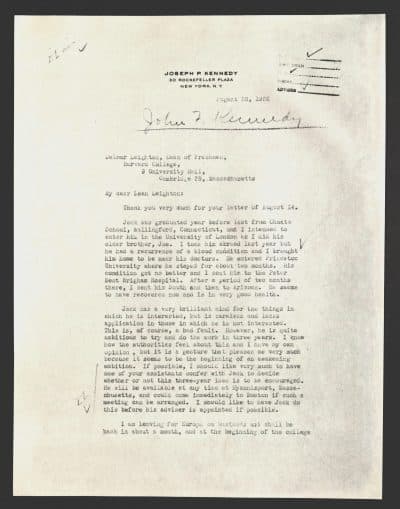

Logevall is finding that beginning as a young man Kennedy had an international outlook, in part because of his father's service as ambassador to the United Kingdom from 1938 to 1940, the last two years of JFK's time at Harvard.

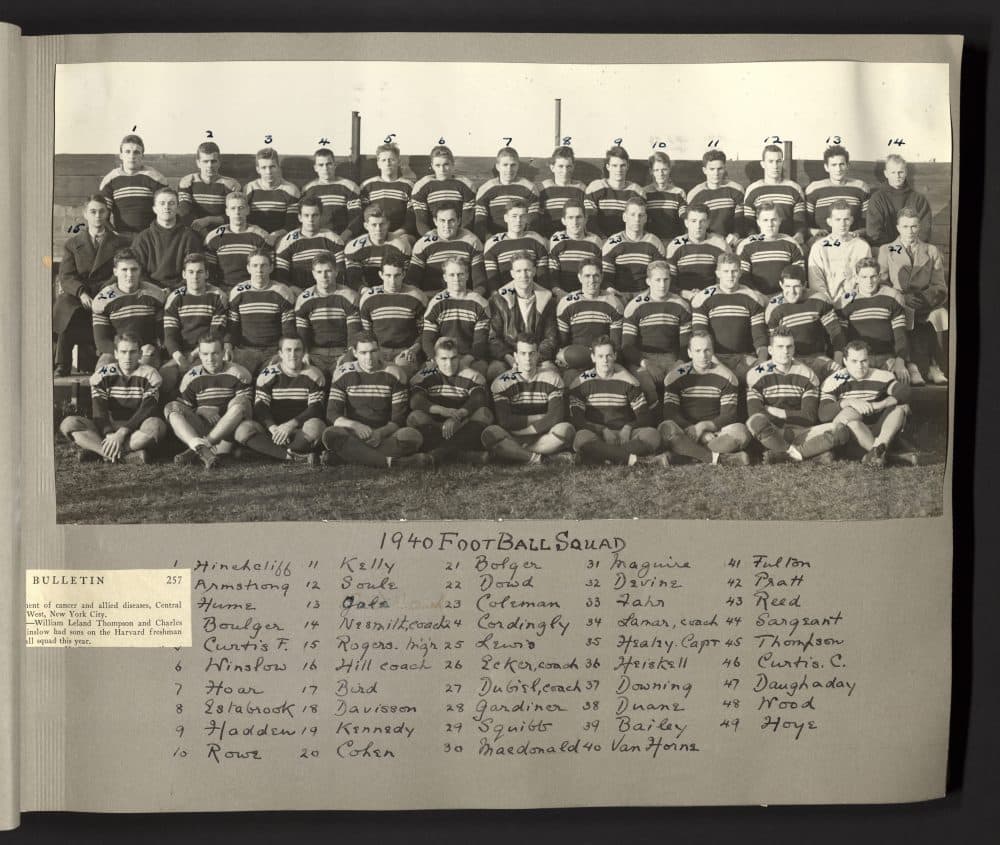

Kennedy was not a particularly serious student to begin with. Logevall says his professors had a kind of middling view of him.

"I don't attach all that much importance to this, because I think he's got bigger things in mind already, much like Franklin Roosevelt when he was at Harvard also was a sort of middling student but had bigger things in mind," Logevall says. "But this is the time when JFK is coming of age intellectually, when his father is in Britain. I think it matters a great deal."

In the Spring of 1939, Kennedy took a leave from Harvard to travel in Europe.

"He's there for these formative, these key moments, and they're bound to have an influence on him, and indeed they do," Logevall says. "When he returns for his senior year and gets to work on this thesis, which will become his first book, professors and others see a newfound seriousness of purpose in John F. Kennedy."

Kennedy's honors thesis, titled "Appeasement at Munich," would eventually be published as "Why England Slept." Joseph Kennedy had been one of America's leading isolationists. At this point, Logevall sees an emerging schism between Kennedy and his father.

"Joe's position is in favor of appeasement," Logevall says. "Joe's position is at least vaguely sympathetic to what the Germans are trying to achieve, or at least thinks that there is a substance to German grievances and also thinks that the Germans are probably unstoppable. Jack, I think, gives a very different perspective."

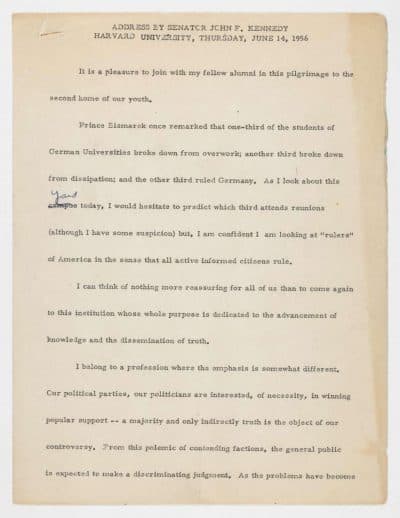

Years later, well into his political career, Kennedy delivered the commencement address at Harvard. Last week, the Harvard Archives released the audio of that speech.

Kennedy was advocating the involvement of scholars in the formation of public policy.

"The people desperately seek objectivity, and a university such as this fulfills that function, and the political profession needs both the technical judgment and the disinterested viewpoint of the scholar to prevent us from becoming imprisoned by our own slogans," Kennedy told the crowd assembled in Harvard Yard.

It was 1956. Kennedy was a U.S. senator. Sniffin-Marinoff says in part, Kennedy was atoning for not standing up more to his Senate colleague, Joseph McCarthy, who had terrorized academics and others with political witch hunts.

"And the feeling was that Kennedy had not jumped in with both feet in that issue as a senator, young person coming in." Sniffin-Marinoff says. "In some ways, I think there's a feeling that he may have tried to address that in this commencement speech, a theme of which was really trying to get the people who work in academics and the people who work in the government to work more closely together and to support each other mutually."

If Kennedy had not become a politician, Logevall could imagine him as a historian or a journalist.

"I think there's no question that Jack was the intellectual in the family," Logevall says.

This segment aired on May 23, 2017.