Advertisement

To Some, Easiest Nitrogen Fix For Long Island Sound Is Not Necessarily The Fairest

Resume

This report is the second in a two-part series. See the first story here.

Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Vermont wastewater plants along the Connecticut River are waiting to hear from the Environmental Protection Agency. Even without specifics, managers at the larger plants know they will be required to adjust the amount of nitrogen in their treated wastewater, considerably lowering the levels, potentially at a high cost.

While nitrogen in the river’s freshwater is not a problem, in saltwater, too much nitrogen can be deadly to fish and plants. In the 1980s in New England — a decade after the Clean Water Act and federal funds built wastewater treatment plants around the country — nitrogen became a big problem in Long Island Sound, where the 400-mile-long Connecticut River ends.

In 2001, the EPA set strict nitrogen output limits on New York and Connecticut’s wastewater treatment plants.

By the end of the year, the agency is expected to issue nitrogen regulations which, without federal funding, could require plant retrofitting, or a major rebuilding of systems.

Feeling 'Forced To Accommodate Nitrogen'

At the wastewater treatment plant that serves Springfield, Mass., and six other towns, additional nitrogen removal will be an enormous undertaking, said Josh Schimmel, executive director of New England’s second-largest wastewater treatment plant.

“The reality is that municipalities are being forced to accommodate nitrogen, and it's on our shoulders, and it's costing a lot of money,” Schimmel said. He wants proof from the EPA, he said, that nitrogen is actually going from his plant located across the river from the Basketball Hall of Fame into Long Island Sound, which is about 70 miles away.

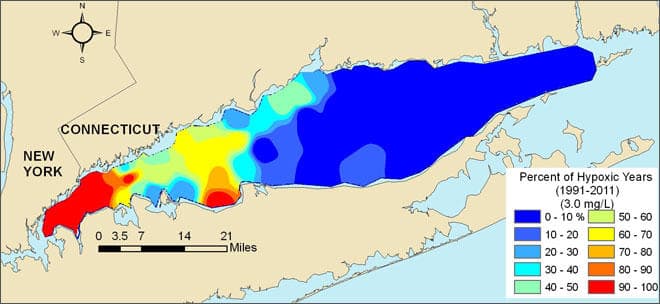

Schimmel has a map of Long Island Sound on his desk, color coded to show where the water is healthy — and where it’s not.

The spot where the Connecticut River enters the Sound is blue. But near New York City, the water is all red. That’s where there’s a bad case of hypoxia — not enough oxygen for wildlife, prompted by nitrogen.

“When you look at it, it doesn't make any sense that communities along the Connecticut River are gonna be spending millions of dollars to deal with a nitrogen issue when you see that the issue really is primarily based up on the Hudson and the East rivers in the urban areas of New York City,” Schimmel said.

Schimmel wondered why New York City’s hypoxia problem is his to solve, and he described the EPA’s nitrogen data as “pseudoscience.”

EPA officials said in an email that the agency always “seeks out and uses the best and most relevant data” to make regulatory decisions.

More Data-Gathering, Before Decisions

But more data are needed. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) is gathering some of it at a stream gauge located near Windsor, Conn., just past the Massachusetts border.

John Mullaney, a USGS hydrologist, said that to figure out how much nitrogen is in the river — and how much must be removed — you need to spend years measuring how water flows because land use continually changes, and so does climate.

“One of the things that affects our nitrogen loads here for the Connecticut River is nitrogen that comes in rainfall,” he said, standing on the bank of an area known locally as Thompsonville.

Nitrogen comes from coal and automobile emissions from throughout the region. Drought, heat and cold all impact the data. Mullaney said researchers have to be really careful around the tidal parts of the river, south of where he stood.

“It’s fresh water,” he said, “but interestingly enough, when the tide is coming in, the river flows upstream … [W]hen you’re trying to count that nitrogen, you don't want to count it twice, because it's going to go by once, and then it might go back upstream again, before it goes down again.”

Multiple Sources, But Treated Wastewater Is Easiest To Track

The bottom line — from what the EPA, the USGS and others know with years of data and anecdotal observation -- is that nitrogen that comes all the way down the river from Vermont does arrive in Long Island Sound. But wastewater treatment plants are not the only source.

Septic tanks, farm field runoff and atmospheric contributions, in total, add up to a higher load of nitrogen than the amount that lands in the river from treated wastewater.

These “non-point sources,” though, are hard to track.

The reality is treated wastewater, a “point source,” is measurable. Beth Card, a deputy commissioner at the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, said treated wastewater is also easiest to oversee because of existing state and federal regulations — whether that’s fair or not.

“You know, we also have to remember that we're asking for an investment to protect a resource that a lot of folks who live in the upper watershed will never see, or never enjoy,” Card said.

The Connecticut River is not impaired by nitrogen, Card said.

That doesn't mean Massachusetts and other states get to ignore the problem. They’re in the watershed.

Card does, however, want to make sure the EPA is making new regulations with the best information possible, and said the state is very involved.

“[DEP] is working actively to make sure that all of the partners have a voice in the process,” Card said. That’s before the EPA finalizes regulations and decides what percentage of nitrogen removal will be required north of Connecticut, in order to continue improving the health of the Sound.

Communities Search For Alternative Solutions

Partners in the conversation about what to do about nitrogen include state environmental officials, plant managers, city leaders — and activists like Andy Fisk, the executive director of the Connecticut River Conservancy.

Wastewater plants are not off-base with the concern that they’re doing more than their fair share, Fisk said.

“Communities are looking at the ways they can develop, so that they don't increase the amount of water going into wastewater plants which may be at capacity,” he said.

For instance, some municipalities and businesses are treating wastewater and surfaces at local sites, Fisk said, so it doesn't cause a problem when it runs off.

Other solutions are in the works, like making environmentally sound policy for parking lot development, and establishing more oyster beds to absorb nitrogen.

But, Fisk said, it’s a little late in the game for a conversation about nitrogen limits. He believes the talk should have started 20 years ago.

Now, the discussions have begun with a fight, he said, about EPA data and about how Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Vermont residents will have to foot the bill to clean up Long Island Sound.

This story comes via the New England News Collaborative and was first published by WNPR.

This segment aired on May 31, 2017.