Advertisement

How The Charles River’s Water Quality Is Monitored — And What’s Being Done To Make It Swimmable

At dawn on a balmy August morning, two volunteers are on the Eliot Bridge in Allston, lowering a small, orange-rimmed basket into the Charles River.

The basket is attached to a long black and yellow rope, and inside it there's a plastic bottle. Bubbles appear as the bottle slowly sinks and fills with clear water. The two volunteers, from the Charles River Watershed Association, then lift the basket up, close the container, and put it in a bag of ice.

The bottle will later be delivered to Deer Island, in Boston Harbor. There, the Massachusetts Water Resource Authority (MWRA) will process the water sample for E. coli bacteria and nutrients like phosphorus.

The water quality testing is what tells officials whether — and where — the river is clean enough for swimming.

When we asked you what you want to learn about the Charles, most of you were interested in whether the river is safe for swimming, and how that’s measured. You wanted to know, for instance, what it means when officials say the Charles “is safe 55 percent of the time.”

The short answer is that, apart from sanctioned events, swimming in the river is prohibited, according to the state Department of Conservation and Recreation. However, scientists rely on an elaborate process to measure the Charles’ water quality, and the monitoring helps officials assess the results of pollution cleanup efforts, with the aim of making the entire river swimmable.

Although the Charles is cleaner these days, William Walsh-Rogalski, of the Environmental Protection Agency’s Boston office, says the tests -- which have been conducted for two decades -- are as important as ever.

“The length and consistency with sampling,” Rogalski says, “provide an excellent basis to track our progress on actions to clean up bacterial pollution on the Charles River.”

That Pollution In Context

Over the last 30 years, the Charles’ water quality has improved dramatically. The MWRA has helped reduce sewage discharges into the river and the EPA has led other costly cleanup efforts. Now, the river is a recreational haven for wind surfing, fishing and rowing.

But pollution challenges persist. Weeks after the Charles River Conservancy held its fifth annual “City Splash” swimming event, blue-green algae known as cyanobacteria spread across parts of the river’s lower basin, around Boston. In response, state officials advised people to stay away from certain areas of the river because of the health risks posed by the algae.

Much of the algae have since disappeared, and the advisory has been lifted. However, the blooms have become a regular phenomenon during the summer.

Marc Nascarella, who directs the state Environmental Toxicology Program, says the algae develop when there's an influx of rainwater runoff into the river. The runoff carries pollutants from sources like lawn fertilizer and motor oil. The combination of the nutrients from the runoff and warm summer weather creates a perfect environment for the algae.

The Sampling Process

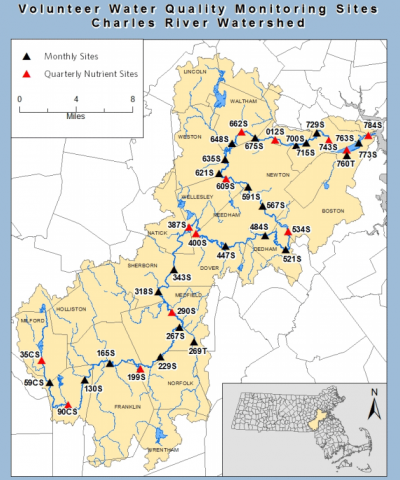

Tests like the one off of Eliot Bridge are part of a monthly monitoring process the Charles River Watershed Association (CRWA) conducts from 35 different locations. In addition to testing for E. coli, volunteers who take the samples measure the water temperature and the depth of the river’s lower basin.

“At each of these 35 sites, once a month, we get a bacteria reading back for that one snapshot in time,” says Julie Dyer Wood, a CRWA project director. “We get a good picture of what it looks like across the river.”

The EPA then compares the test results to state water quality standards and produces an annual report card on the river’s water quality. The agency recently gave the lower basin a “B” for 2016, after giving it a “B+” for 2015. The EPA also said the river was swimmable 55 percent of the time last year -- meaning 55 percent of the monthly samples met the appropriate safety standards. The other 45 percent of the time, swimmers were at a higher risk of being exposed to E. coli.

The CRWA also monitors when the water is safe for rowing and boating. Twice a week during the summer, scientists go out on the river in boats to test the last 10 miles of the river for E. coli. The test results help officials spot parts of the river that may not be clean enough for boaters.

“If the concentrations of [E. coli] are above the public health standard for boating, we will alert the boathouses and they’ll fly different color flags based on the water quality,” says CRWA scientist Katie Friedman.

What’s Being Done To Make The Charles Swimmable

The EPA and the CRWA aim to make the entire Charles swimmable all the time.

Dyer Wood says the river would maximize its recreational potential if people could safely swim in it. A swimmable Charles would also mark the success of efforts to clean it, and could make more people stewards of the river.

“We find that folks who enjoy the parklands and enjoy the water have a firsthand experience with the value the Charles provides to their lives and to our region," she says. "And so those individuals can be great allies in continuing to protect and restore the Charles.”

In order for the river to indeed be safe for swimming, there must be less than 126 colony-forming units of E. coli per 100 milliliters of water. Although public swimming in the Charles is not permitted, several parts of the river meet that standard.

Dyer Wood says such areas are cleaner because they are surrounded by more of a natural green landscape that helps avoid storm runoff.

“It does vary by time. But in the central section [of the river], that’s part of the least developed” and cleanest section, she says. “Like Sherburn and Dover are probably the least developed towns in our watershed.”

In other areas surrounded by more concrete and roads, the CRWA is constructing new green infrastructure to reduce storm runoff.

Although Nascarella, the state health official, says it will be hard to prevent all acid blooms during the summer, cities like Chelsea and Watertown are building special rain gardens and tree pits to absorb and hold the water.

"We’re really focused on having the river be clean enough so we can swim in it," Dyer Wood says. “Only being able to swim somewhere 55 percent of the time might not be that fun.”

Sam Turken was a summer intern with WBUR's digital team.