Advertisement

As Mayor, Tito Jackson Says He Would Reach Deeper For School Funding

Resume

This is the first of two articles on the mayoral race and education. A second, about Mayor Marty Walsh's education policy, was published Friday.

Waving at traffic at the edge of Franklin Park, Tito Jackson is on his home turf.

Jackson grew up less than a mile away in the Grove Hall neighborhood, a stronghold — now, as it was then — of Boston's African-American community.

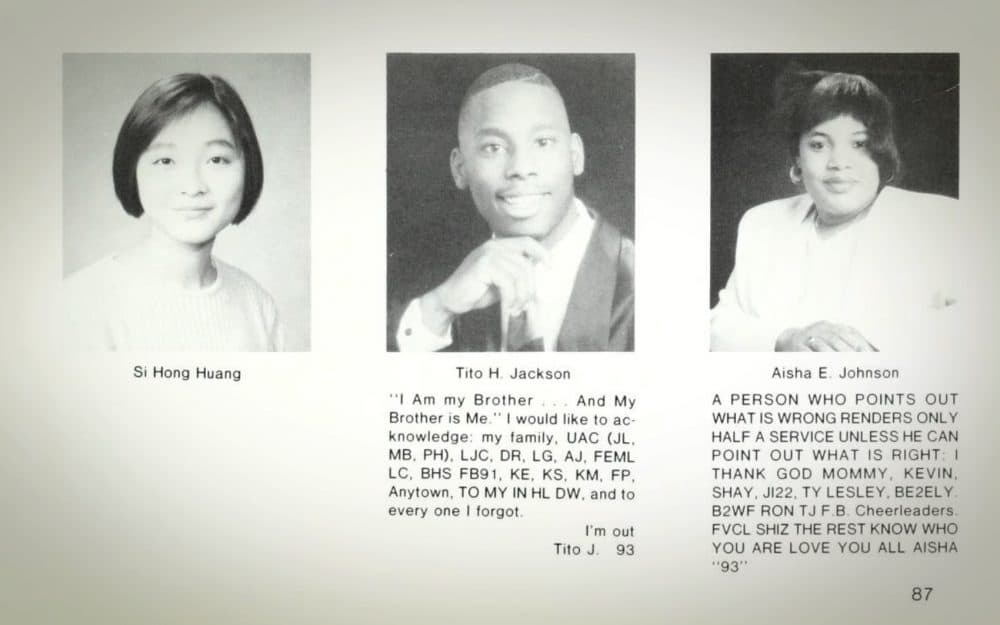

But Jackson didn’t go to high school in Boston. Born to a 13-year-old mother, he was adopted by parents who decided to take him out of the Boston Public Schools.

Instead, he went to Brookline High as a METCO student; he graduated in 1993. Jackson said he's grateful for the experience.

“What my parents did is what every single parent in Boston is doing — trying to do the best for their child.”

Jackson said he worries that a Boston Public Schools education still isn’t a surefire pathway to a bright future for all of its students.

“The real issue," he said, "is that a young Martin J. Walsh and a young Tito Jackson wouldn't fare as well under a Walsh administration — based on the funding that's currently happening.”

That's the magic word at the center of Jackson's education-focused campaign: funding.

When thousands of BPS students walked out of class last year to protest millions of dollars in planned budget cuts, Jackson threw his support behind them. And he emerged as a leading advocate for more spending on public schools in last year's debate over Question 2, which would have lifted a statewide cap on charter schools.

The ballot question went down in defeat by a nearly two-to-one margin. It was a major victory for Jackson, and he's been making the case for school funding ever since.

Jackson said that, if elected mayor, he’d reallocate $45 million directly to public schools in Boston. That's a lot of money, especially coming on the heels of the $20 million infusion in Mayor Walsh's most recent budget.

Jackson said it would allow them to add staff members sometimes seen, or even cut, as inessential, like computer science teachers, nurses and social workers.

But supporters of Walsh say it's not that simple. Like Marty Walz, the former state legislator who was on the other side of the charter debate last year.

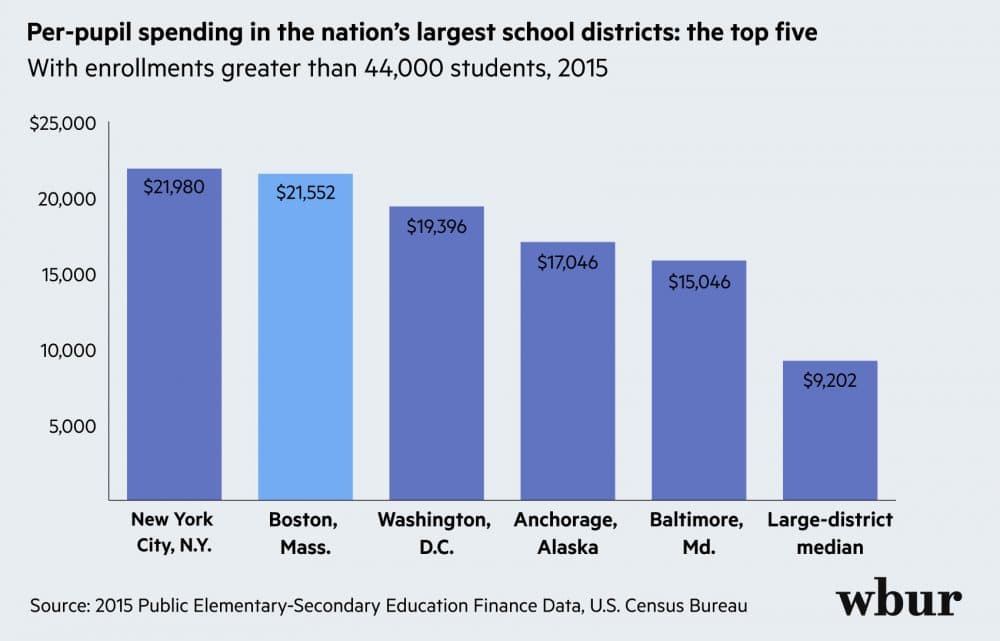

"More money is not, alone, going to do the trick," Walz said. "Because we already spend so much, and don't get the kind of return on that investment that we should get."

She pointed to a chart that shows Boston spends around $20,000 per pupil — markedly more than most of the nation’s biggest school districts and second only to New York City.

Walz said about half of all BPS students attend schools that the state has labeled as underperforming.

So while she supports increased funding, Walz said the district also has to change its ways to better serve low-income students and English-language learners. The high performance of some urban charter schools suggests that even high-needs students can thrive academically, given the right academic community, as Walz pointed out.

"How do we do a better job educating the kids that are hard to educate?" Walz said. "That's the duty of adults — to figure this out!"

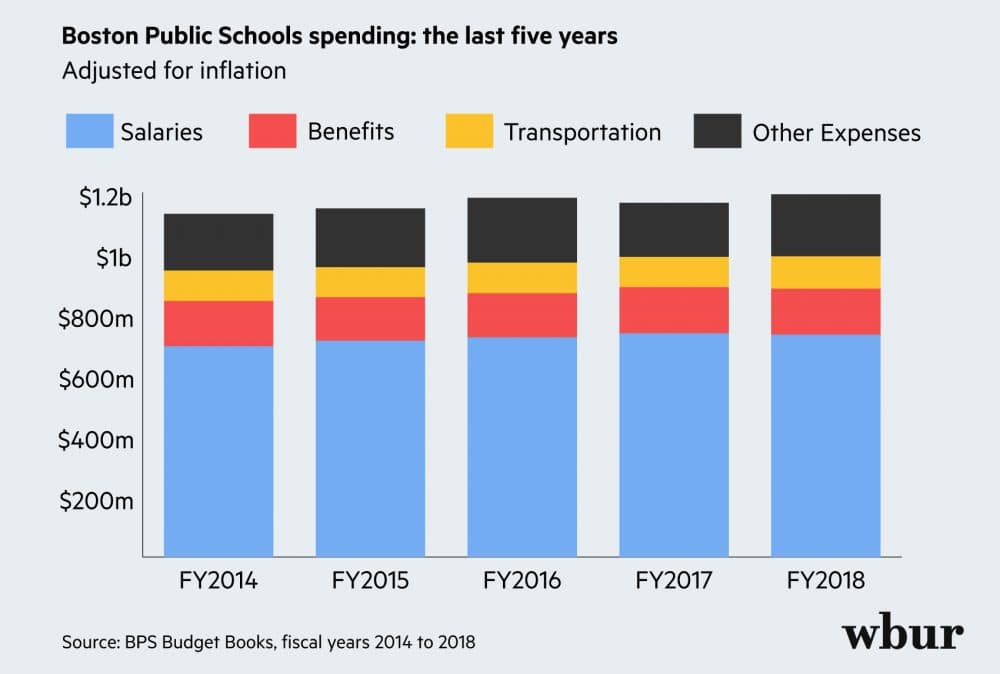

Walsh supporters also point out that even after adjusting for inflation, BPS funding is actually up over the past five years by more than 5 percent. And spending on the district now accounts for more than a third of the city's overall budget.

But Jackson and his supporters respond with data of their own.

Since 2012, BPS has employed "weighted student funding,” a formula that attaches the district's money to follow its students. That means as enrollment drops at a given school, it can create a kind of death spiral: less funding, dwindling staff and many students stuck at the school.

Kristin Johnson, a BPS parent who's supporting Jackson, gave an example.

"Their art teacher gets cut, they lose half a nurse, they lose their music, they lose their AP classes," Johnson said. "It’s an issue of quality and equity."

As of this school year, state data show that about half of Boston's public schools have fewer teachers than they did when Walsh took office in 2014. Most have no working library. About 50 schools will see cuts this year — many of them attended by especially high-needs populations, according to Johnson's analysis.

Even the district concedes that recent funding decisions have been difficult. In a letter sent home to families last year, BPS Superintendent Tommy Chang cited state and federal aid, which hasn't kept up with rising costs.

But Jackson says he learned a lesson going to school in wealthier Brookline. It's almost a civic tradition there to fund education richly, and its citizens voted overwhelmingly to approve higher taxes to pay for schooling just two years ago.

“What I learned in Brookline is, that's a school system where, when money runs out, they make it work," Jackson says.

Both Mayor Walsh and Superintendent Tommy Chang might point out that Boston isn't Brookline, and they're managing more variables and competing demands — with less help from outside the city.

This segment aired on November 2, 2017.