Advertisement

Ed Commissioner Finalists

Angélica Infante-Green Hopes To Build On A New 'Blueprint' For English Learners

This is one of our profiles of the three finalists for Massachusetts Commissioner of Elementary and Secondary Education. Each of the finalists will be interviewed publicly on Friday. Board members plan to vote on the next commissioner on Monday. You can read our profiles of the other two finalists, Jeff Riley and Penny Schwinn.

When she speaks with her children mostly in Spanish, Angélica Infante-Green is keeping to professional best practices.

In the spring of 2014, as a senior official in New York state’s Department of Education (NYSED), Infante-Green — the bilingual daughter of immigrants from the Dominican Republic and a lifelong New Yorker — led the effort to develop a “blueprint” for English language learners in the state.

It affirmed that “all teachers are teachers of English language learners,” and imagined a learning environment that “recognizes and respects the languages and cultures of all students.”

New York’s Department of Education has been building on that blueprint ever since. Last year, Massachusetts education leaders followed suit: pivoting from a model of “sheltered English immersion” with the overwhelming passage of the LOOK Act, which featured a similar suite of changes.

If Infante-Green is chosen as the next commissioner, she would inherit oversight of language-learning reform — based on that rough blueprint — in a new home state.

At a New America roundtable last year, Infante-Green described the plan as an attempt to envision a sea change in the way public schools serve English learners. At the moment, the American education system tends to approach English learners with “the most inappropriate tools,” Infante-Green said.

The proof, she argued, is in numbers “we see every day.” Nationwide, English learners graduate less often and drop out more than almost any other large subgroup of students. And the population, taken as a whole, exhibits disproportionate levels of poverty and trauma compared to students of European descent.

Massachusetts is no exception: graduation and dropout rates in immigrant enclaves like Chelsea and Lawrence remain well above the state average.

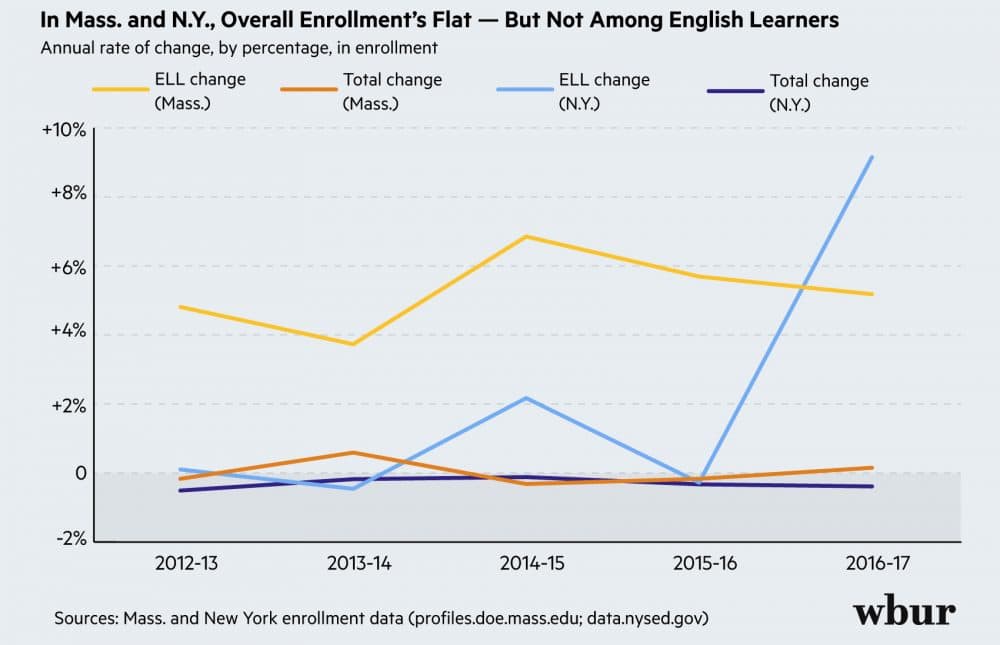

And yet, while overall enrollment in New York and Massachusetts holds steady or shrinks, the percentage of students identified as English learners keeps growing year over year.

It’s a dynamic John King, the former U.S. Secretary of Education who handed the keys to Betsy DeVos, still watches from afar. King’s first leadership role in education was as co-founder of Roxbury Prep in Boston, which became the state’s highest-performing urban school. In 2011, King returned to his native New York to become commissioner of education there.

“Massachusetts is the highest-performing state in the country, but it’s not high-performing for everybody,” King said. “There are significant achievement gaps for Latino students, for African-American students, for low-income students — and real work that needs to be done to try to close those gaps.”

In A Second Language, "Value ... For Everyone"

First in New York City, then at the state level, Infante-Green looked for cases where English learners were being well-handled. She told the New America roundtable that she saw the best results in a particular state of affairs: where a “whole-school approach” recognized the power of each of its students’ home language, “the value that it has for everyone.”

In New York, following 2014 guidance from the state’s board of regents, that meant a statewide commitment to robust bilingual education, especially on a dual-immersion model in which a class is split between native English speakers and students whose first language is, say, Spanish or Mandarin Chinese.

Two teachers, working in tandem, split the day up into linguistic segments: some English immersion, some immersion in the second language. (It’s this kind of environment that Infante-Green has tried to develop in her own home — her husband, who has roots in Barbados, being her English-speaking “co-teacher.”)

This model repositions second-language literacy as an education asset, not a deficit. And it tries to build bilingualism, which — research suggests — can provide cognitive and socio-emotional benefits. And dual-language learning has shown promising results against persistent achievement gaps.

The language reform in New York also offered teachers additional training in serving English learners, translated the math curriculum into five common languages and introduced a “state seal of biliteracy” which certified and commended students who had shown in mastery in more than one tongue. The Massachusetts legislation passed last year borrowed the state-seal idea entirely.

"Angélica's very passionate about education equity for low-income students, for students of color, for English learners. That passion comes across in all the work that she does to bring teachers and principals together around a vision."

Former U.S. Secretary of Education John King

A 'Difficult' Transition In New York

The change in classrooms, which began in 2016, wasn’t perfectly graceful. New York’s 200,000-plus English learners present a complex array of assets. Seventy percent of them live in New York City. Only two-thirds are Spanish speakers; the rest speak a diverse mix of other languages, especially Mandarin, Bengali and Arabic.

As those changes went into effect in 2016, a city official told The New York Times that finding an adequate number of teachers fluent in those languages as “very, very difficult.” Others faulted state officials for allotting just $1 million to implement the change that would involve hiring thousands of new teachers.

Union officials and other community members declined to comment on the record about Infante-Green, because they expect to continue to work with her if she isn't named Massachusetts' next education commissioner.

King conceded that New York’s transition was “a challenge,” but one that extends well beyond the state borders. “As a country, we're not preparing enough bilingual educators,” King said, “but Angélica has brought superintendents and teachers and labor and higher education together around the goal of increasing the supply. And certainly the state’s making progress.”

An Act-Fast Attitude

Infante-Green has said she was drawn to the classroom by the prospect of making change in the lives of students. Like her fellow finalists for the commissioner job, she’s an alumna of the Teach For America program and exhibits the missionary zeal that sometimes comes with that intense, early work experience.

Her climb into administration was prompted by the frustration she felt as a young teacher. In a video for Chiefs For Change — an education reform group she joined that was founded by then-Florida Gov. Jeb Bush — she remembers “there were policies that were being made without really knowing what was happening in the classroom or taking into account what was happening in the classroom. So I decided that I was going to bring that drive to create change at a different level.”

So while parent-advocates for English learners in New York admitted that there’s much work left to do, many celebrate Infante-Green’s act-fast attitude.

Kim Sweet, the president of New York’s Advocates For Children (AFC), which lobbies for English learners and students with disabilities, described Infante-Green as an advocate herself. She called her “a fighter for the students" who candidly brings her experience of parenting two bilingual children, one who is autistic, to the table.

“She doesn’t have a lot of tolerance for bureaucracy that she sees as standing in the way” of that fight, said Sweet, even as Infante-Green climbs the ladder of New York’s education hierarchy. “Sometimes that can irk people,” she added, especially in the unions and the state’s established order.

You can hear that impatience in Infante-Green’s public statements on ELL reform in New York. She said in the New America roundtable that she’s excited “to see the fruits of these changes three or four years from now,” but disappointed that change couldn't have come sooner.

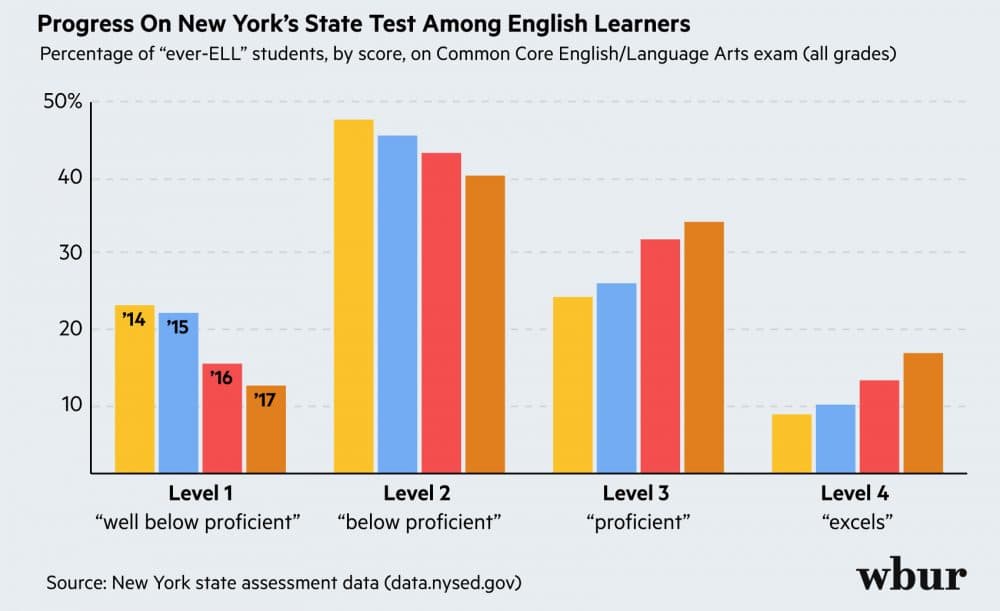

Test scores among students classified as English learners have indeed begun to climb. And even at this late hour, nearly 500 people have signed a petition addressed to Mayor Bill de Blasio to keep Infante-Green at home in New York, to replace the city's retiring chancellor of schools. (De Blasio's office did not respond to requests for comment.)

For his part, John King, the former education secretary, drew a New York analogy for what would await Infante-Green if she was chosen as ed commissioner in Massachusetts. King admired Mitchell Chester as a friend and mentor, and someone who was "able to get so much done."

But Infante-Green cares deeply, too, King said.

"Angélica's very passionate about education equity for low-income students, for students of color, for English learners," he said. "That passion comes across in all the work that she does to bring teachers and principals together around a vision."

When it comes to replacing, King joked: "If you'll forgive the Yankees reference, for all your Red Sox fans, it's sort of like taking over from Joe Torre." But, he added, his former deputy might be the person to pull it off.