Advertisement

MFA Proves The '50s Femme Fatale Archetype Has Evolved Into The Present Day

Here she comes, you better watch your step

She's going to break your heart in two, it's true...

Little boy, she's from the street

Before you start, you're already beat

She's gonna play you for a fool, yes it's true

'Cause everybody knows,

She's a femme fatale.

— The Velvet Underground & Nico, “Femme Fatale”

Dangerous dames have long been a staple of pulp fiction, with the classic femme fatale luring foolhardy men to dire fates on almost a weekly basis during the film noir boom of the 1940s and '50s. The phrase alone conjures black-and-white visions of Venetian blinds and countless cigarettes, allegorically exposing male anxieties of powerlessness in a changing post-war world. But the Museum of Fine Arts’ “Femmes Fatales” series (running March 2 to 18) makes a case for the archetype evolving through the decades into the present day.

Showcasing eight films released between 1935 and 2014, the retrospective has room for vindictive vixens ranging from Marlene Dietrich’s Mata Hari in “Dishonored” to the skateboarding Iranian vampire vigilante in Ana Lily Amirpour’s “A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night.” There’s Luc Besson’s fetishized superhero assassin “La Femme Nikita” and Scarlett Johansson’s literal man-eater in Jonathan Glazer’s mesmerizing “Under the Skin.” It’s a fine selection if you want to study advancing gender roles in genre cinema, and works just as well if you like to go to the movies to look at beautiful women.

The series kicks off Friday, March 2, with “Gilda,” director Charles Vidor’s sordid 1946 melodrama in which Rita Hayworth basically brings down an entire Buenos Aires gambling empire with an iconic flip of her hair. (She makes such an entrance here that 50 years later “The Shawshank Redemption” built an entire scene around its characters sitting around watching it.) She’s playing a moll for mobster Ballin Mundson (George Macready), who has no idea his muscle man Johnny Farrell (a terrifically seedy Glenn Ford) just so happens to be Gilda’s ex.

“Women and gambling don’t mix,” Mundson advises Johnny more than once throughout the picture, and the dysfunctional, love-hate spasms of Hayworth and Ford slowly tear apart this smoothly operating criminal enterprise with a blunt-force emotional cruelty that still feels jarring when watched today. The homoerotic tension between these male characters is pretty much off the charts, and one can only assume all the envelope-pushing scared skittish studio executives resulted in the film’s incongruously happy ending, which feels tacked on not just from another movie, but from another planet.

Friday night’s second feature is an inspired pairing. The third film by Joel and Ethan Coen, 1990’s melancholy “Miller’s Crossing” sees Irish mob boss Leo (Albert Finney) and his right-hand man Tom (Gabriel Byrne) torn asunder by Marcia Gay Harden’s vamping Verna. Set in a heightened fantasy vision of 1930s gangster movies, the movie boasts some of the Coens’ most beautifully stylized dialogue, with the characters speaking a poetic patois that’s at first impenetrable, and then endlessly quotable.

Echoes of “Gilda” abound as Tom and Verna sneak around behind Leo’s back, but like most things in this movie, their affair is soaked in whiskey and regret. Look beyond the pristine production design and you’ll find one of the siblings’ saddest and most soulful pictures, with a surprising amount of sympathy for the personnel management headaches of a rival Mafia capo, beautifully played by the late Jon Polito. He practically steals the film outright, assessing the movie’s mountain of double-crosses with a heavy sigh. “Running things,” he grunts. “It ain’t all gravy.”

Of course you can’t have a femme fatale series without Barbara Stanwyck’s Phyllis Dietrichson in “Double Indemnity.” She’s such an embodiment of the archetype that Rebecca Romijn actually watches Billy Wilder’s 1944 picture for inspiration at the beginning of Brian De Palma’s lurid, late-period 2002 masterpiece “Femme Fatale” (a movie sadly not included in this series but well worth seeking out, as it’s about as much fun as these things get.)

Adapted from the scandalous James M. Cain novel by Wilder and Raymond Chandler, “Double Indemnity” offers at least four or five movies’ worth of sardonic quips, while Fred MacMurray’s smooth-talking insurance salesman Walter Neff immediately succumbs to the charms of Stanwyck’s black widow. The film’s framing device finds him gutshot and bleeding out, but we can see Walter’s already a dead man the first time he lays eyes on Mrs. Dietrichson and her ostentatious anklet descending a staircase.

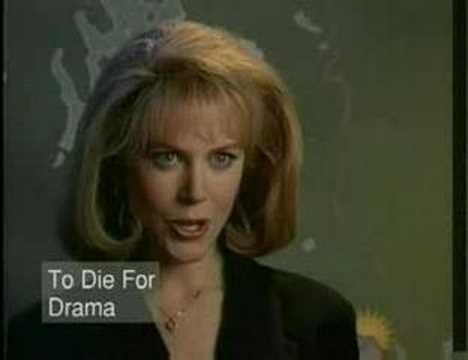

“Double Indemnity” got a tabloid TV makeover half-a-century later in Gus Van Sant’s “To Die For,” a hit with critics but not audiences back in 1995, and it’s the movie in this series most deserving of a second look. Loosely based on a Joyce Maynard novel that was itself inspired by the Pamela Smart case that had recently rocked New Hampshire, the film stars Nicole Kidman as a cravenly ambitious TV weather girl who seduces a dopey teenager (Joaquin Phoenix) and convinces him to kill her husband (Matt Dillon.)

The legendary Buck Henry’s hyper-acerbic screenplay cuts through mid-'90s daytime television self-help clichés with a scalpel, playfully putting the grieving relatives on an exploitative afternoon talk show while Van Sant mixes up the media between faux-documentary, heavy drama and straight-up satire. (This is the movie “I, Tonya” was trying so desperately to be.) Kidman earned kudos for her broadly comic performance as an empty, sociopathic fame-chaser, but “To Die For” never becomes glib because Van Sant can’t help but keep erupting with compassion for her victims.

Illeana Douglas brings ballast to the laughs with what should have been a star-making performance as Dillon’s grieving sister. The empathy extends to the trio of dim-bulb teens falling into Kidman’s web — the frightfully young Phoenix, potty-mouthed sidekick Casey Affleck and most affectingly a sexually confused tomboy played by Wellesley’s own Alison Folland. Beneath the film’s day-glo colors and Swiftian cultural commentary beats a battered, broken heart.

Watching “To Die For” these days it’s tough to shake the idea that Kidman’s character would probably end up with her own reality show. But then I think so would Mrs. Dietrichson. Maybe Gilda, too.

The MFA’s “Femmes Fatales” series runs from March 2 through March 18.