Advertisement

How A Sore Wrist And A Fondness For 'Noise' Forever Changed The Way The Violin Is Played

Resume

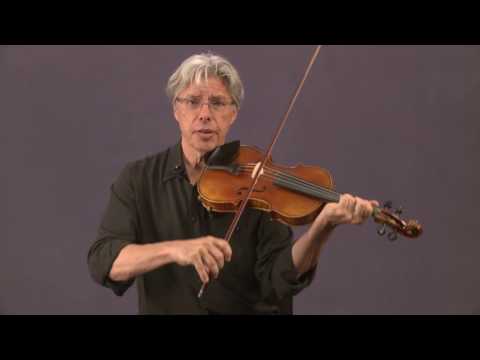

Darol Anger grips his bow loosely, wrist bent, and smacks it against the strings of his fiddle. The resulting sound, a small crunch, is like the crackle of a very tiny drum.

“You can get some nice kind of ska rhythms going,” Anger says as he moves through a simple chord progression, each bow stroke accented by that same percussive snap. “Basically what we’re getting here, we’re modeling the high hat and snare of a drum kit.”

I've caught Anger at his soon-to-be former apartment in Arlington as he prepares to move back to his home state of California, after nearly 12 years in Boston, where he was on the faculty of Berklee College of Music. Right now, he’s in full professor mode, keeping a running commentary as he demonstrates a technique that he has become known for: the chop.

The technique, which has existed for about 50 years, took the fiddle-playing world by storm — spreading from North America, with a particularly strong scene in Boston, to Europe and Canada — and changed the way the violin is played today.

“It’s almost like the point of the shovel going into the dirt,” Anger explains. “The bow comes down, sits on the string, and then you get another sound by kind of bringing the bow back up off the string.”

Anger makes the chop look simple, but that little crunch has defined his career. In 1985, he co-founded a group called the Turtle Island String Quartet in San Francisco. The ensemble earned accolades for its groundbreaking infusion of jazz into a classical context. Crucial to its success was the chop, which allowed the string ensemble to provide its own rhythm section.

“We wanted to do everything. ... We wanted to prove that the string quartet was capable of any kind of music, even contemporary music,” Anger says. “And so the chop became the drums and bass and rhythm guitar.”

In the '80s, Anger developed the chop into an incredibly versatile rhythmic tool. Today, it’s everywhere — in bluegrass, jazz, even Celtic music. When I was learning to play the fiddle as a teenager in the early 2000s, chopping was all the rage. Since then, I’ve wanted to know: How did this happen? How did musicians figure out a totally new way of playing an instrument that’s been around for centuries?

To answer that, you have to start with the guy who taught Anger to chop in the first place: Richard Greene.

Greene is a fiddle player and photographer from Los Angeles. He got one of his first gigs in 1966 with Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys. Greene says he wasn't very good at the fiddle at that point, and kept rushing the music. So Monroe told him to stop playing melodic fills and just stick to rhythm. Soon, the fiddler began experiencing chronic pain in his bow arm.

Greene had already begun experimenting with a chop-like technique, and suddenly it clicked. “I dropped the bow ... near the frog, as a way of just resting my painful wrist and arm,” he explains. “And then when I would lift my bow up, there was a free sound, the pinch on the string. So that was how it began: drop the bow and pinch. And it takes no energy whatsoever. The mother of this invention was pain and laziness.”

Not long after his stint with Monroe's band, Greene helped found the folk-rock fusion band Seatrain, and it was there that he began incorporating the chop into more complex bowing patterns. Darol Anger remembers seeing the band in the early ‘70s.

“He was using it as sort of this bravura solo thing, like the band would stop and he’d go crazy and he’d chop all over the place and it was great,” Anger recalls. “And then the band would come back in and people would scream and just do whatever it is people do when they’re in ecstasy. And I was in ecstasy. It was amazing, it changed my life."

Pretty soon Anger was using the chop in his own music, and he started teaching it to musicians — mostly at fiddle music camps in the summer — who in turn taught it to their friends. By the 2000s, the chop was a full-blown phenomenon. It flourished in Boston, where alternative string players flocked to attend Berklee College of Music and New England Conservatory, and traveled overseas. (For more on the chop's evolution and dissemination, read fiddler and musicologist Laura Risk on the subject.)

But it was also a bit controversial. Some musicians thought the chop was too modern; others found it showy and obnoxious.

Greene compares the chop to other extended techniques on instruments like the saxophone and piano, part of a trend in acoustic music toward experimentation, and, well — noise.

“The world of noise is now added to the world of musical instruments,” Greene says. “It’s great to add noise to … the violin. It’s a great thing. It gives it some life, gives it some grit.”

So, 50 years after the chop’s invention, how is it faring today?

At bluegrass night at the Cantab Lounge in Cambridge on a recent Tuesday, fiddler Patrick M’Gonigle deployed a couple different chopping patterns, though somewhat sparingly. M’Gonigle told me that when he first learned how to chop, he used the technique all the time, enamored with the virtuosic stylings of Anger and the bluegrass fiddler Casey Driessen. Being able to chop was especially useful when there were no other rhythm players around. But it could also be disruptive in an ensemble setting.

“Darol Anger had a great quote once which was: ‘Teaching people to chop is like giving people a knife. It’s a very useful tool, but it’s also very dangerous if used improperly’,” M’Gonigle says. “And I feel like that’s kind of how I think about the chop.”

“Do you think it’s here to stay?” I ask.

“Oh, for sure. 100 percent.”

Maybe the chop is the auto-tune of the string world: For a while, it was all the rage, and you either loved it or hated it. And now, like electric guitars and synthesizers and holograms of dead pop stars, it’s just part of the landscape. Like it’s been here all along.

Featured on this segment are "Sidewinder" by the Turtle Island String Quartet, "Bluegrass Breakdown (Live)" by Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys," "13 Questions" by Seatrain and "Polka Upstairs" by Darol Anger's Republic of Strings.

This segment aired on October 25, 2018.