Advertisement

Dixville Notch's 'First In The Nation' Midnight Voting Tradition May End Over Election Rules

Resume

Once every four years, for a brief moment, it seems the whole world turns its eyes to Dixville Notch.

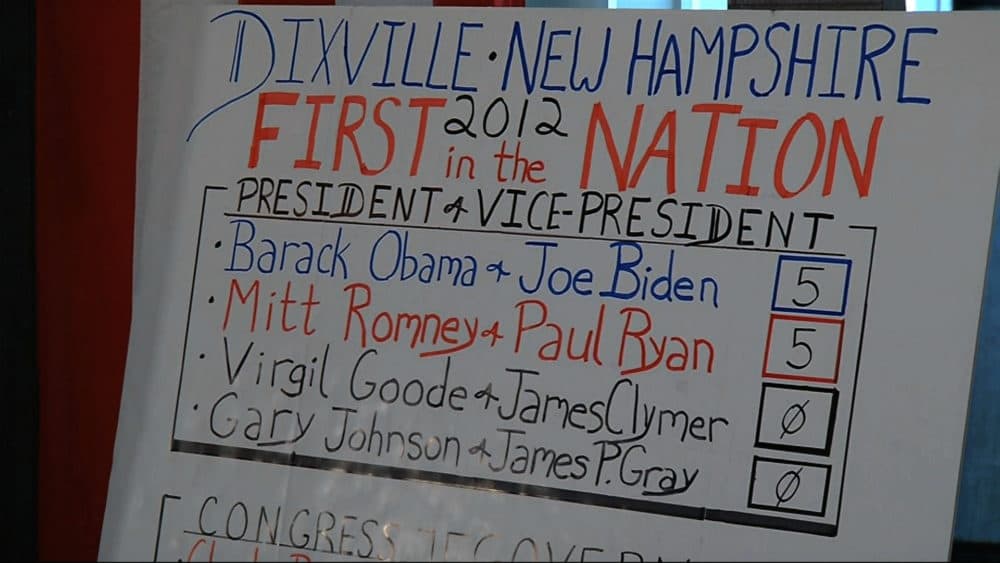

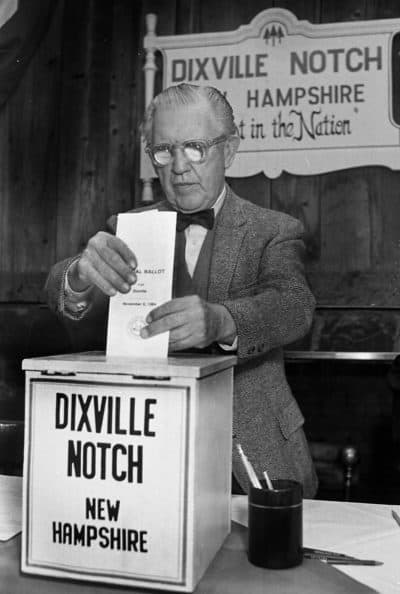

Since 1960, voters in this tiny Coos County community have been casting their ballots just after the stroke of midnight to mark the official start of the New Hampshire presidential primary.

But Dixville Notch has lately found itself under a different kind of spotlight: from the New Hampshire attorney general’s office. Shortly after the 2016 election, state election investigators started scrutinizing Dixville Notch’s voter checklist and, along the way, found a pattern of potential problems with its election procedures.

As one investigator put it, in a report shared with NHPR: “What started out as an investigation into a complaint involving one voter, who may not have been a resident of Dixville … has appeared to uncover a potentially more pervasive issue with respect to the process in Dixville as a whole.”

Like what you're reading? You can get the latest political news (and other stories Boston is talking about) sent directly to your inbox with the WBUR Today newsletter. Subscribe here.

The people singled out in the state’s investigation maintain they did nothing wrong, that Dixville Notch’s elections are “absolutely trustworthy” and that the attorney general’s office seemed to blow the situation out of proportion.

But this heightened scrutiny could have serious implications for one of New Hampshire’s proudest political traditions: If Dixville Notch can’t get its act together, the state says it won’t be allowed to hold its midnight vote in the 2020 presidential primary.

“Things change over time in communities, and sometimes those changes are difficult and traditions end,” said Associate Attorney General Anne Edwards. “But the attorney general’s responsibility is to enforce the election laws.”

A Decades-Long Dilemma

Dixville Notch isn’t the only place in New Hampshire that opens its polls at midnight for the presidential primary. But it’s kept its tradition running the longest, so it gets most of the press coverage. Take it from Peter Johnson, who cast a ballot there for more than 30 years and offered up interviews to reporters from all over the globe who took an interest in Dixville Notch’s early returns.

Through the years, Johnson’s political commentary has appeared everywhere from CNN to the Sydney Morning Herald. He’s made cameos in videos by The Associated Press, photos from Reuters, news articles for audiences in Costa Rica, Paris and Singapore.

The thing is, all of those stories left out one crucial detail: Johnson doesn’t actually live in Dixville Notch. And he hasn’t for decades.

That key fact did come to the attention of New Hampshire election investigators in January 2017, amid a broader inquiry into potential voting irregularities in Dixville. And while Johnson’s story is complicated, it illustrates some of the forces at play in a community where personal ties to the midnight voting tradition run deep.

Johnson, for instance, did own a home in Dixville Notch in the 1980s, and registered to vote there at that time. However, that property got tied up in a messy divorce case that dragged on for years and even ended up before the New Hampshire Supreme Court.

While Johnson was waiting for the dust to settle on the case, he found new places to call home. He split his time between other towns in New Hampshire — mainly Campton and North Bridgewater — as well as a cottage on Martha’s Vineyard, from which he ran a business selling fishing lures. (New Hampshire files say Johnson left his home in Dixville Notch in 1999, but Johnson told NHPR he actually moved away in the early 1990s.)

While his residences might have been disparate, Johnson said he remained crystal clear on one point: He always planned to return to Dixville Notch.

“I loved it up there; it’s beautiful,” Johnson said, explaining that he lined up a right of first refusal on another property in town and has been waiting for it to come back on the market.

Johnson, who now lives in Newport, said he believed that “intent to return” was a valid reason to keep voting there, under New Hampshire election law. So that’s where he kept voting.

“Does it make any difference when I vote for Donald Trump, whether I vote in Campton, N.H., or Newport, N.H., or Dixville Notch, N.H.?” Johnson said. “As far as I know it doesn’t make one damn bit of difference at all.”

“Does it make any difference when I vote for Donald Trump, whether I vote in Campton, N.H., or Newport, N.H., or Dixville Notch, N.H.? As far as I know it doesn’t make one damn bit of difference at all.”

Peter Johnson

The people in charge of enforcing New Hampshire’s election laws say it does, indeed, make a difference. After reviewing his case, the attorney general’s office sent Johnson a cease and desist letter instructing him to stop voting in Dixville Notch until he establishes a clearer claim of domicile there.

“We would be the first to admit that sometimes determining domicile can be confusing,” Associate Attorney General Edwards said, “because there is a provision in domicile law that allows for an individual to have an intent to return based on temporary absence.”

But Edwards said it’s important to look at all of the factors when determining someone’s voting eligibility. In Johnson’s case, the state homed in on the fact that he had no physical presence in Dixville Notch outside of election season and designated his addresses of record — for his driver’s license, vehicle registration, business and more — elsewhere.

“It’s hard to say that really is a ‘temporary’ absence,” Edwards said, “given that during that 20-year period, that individual’s life went on in a different community.”

Resort Closure Spurs Residency Questions

Peter Johnson wasn’t the only Dixville Notch voter to get a call from state election investigators in the last few years. The attorney general’s office started looking into his case only after it received several other election complaints about Dixville Notch, all involving people who used to work at the now-shuttered Balsams Resort.

For the last half-century, Balsams’ employees made up the bulk of Dixville Notch’s voting population. Many lived on-site at the Balsams, so when the hotel closed down in 2011, they didn’t just lose their jobs — they also lost their homes.

One of those former employees, longtime Balsams’ Entertainment Director Rick Erwin, recalls the period after the hotel’s closure as one of great uncertainty — especially in his role as Dixville Notch’s town clerk.

Employees were told the Balsams would reopen eventually, Erwin said, but the timing was unclear. He sought guidance from the Secretary of State’s office about whether he and other displaced Dixville Notch voters could retain their registration while they waited to see if the hotel would come back to life.

“They confirmed at that time, as that law was written — with the situation at the hotel, we were hopeful to return there to work — we would still remain residents there, intending to return,” Erwin said.

With that advice, Erwin and his wife kept their spots on Dixville Notch’s voter checklist for the 2012 elections. They didn’t realize this was a problem until they got a call from the attorney general’s office in 2013, investigating a complaint about their registration status.

The attorney general’s office dismissed the complaint against the Erwins, and instead encouraged the couple to re-register in their new hometown. Erwin said he had no problem making this change, because by then it became clear the Balsams redevelopment was taking much longer than he anticipated.

The secretary of state’s office did not respond to a request from NHPR to clarify what advice they provided to Erwin and other Dixville Notch voters questioning where to claim domicile.

According to a report from the attorney general’s office, it was “unclear from the case file as to whether or not election officials in Dixville” were notified about the 2012 complaint against the Erwins. This might explain why, in 2016, the state dealt with a similar case involving another former Balsams employee.

On the day of the 2016 general election, a state polling inspector received two separate complaints about Jacques Couture, who also kept voting in Dixville Notch — his home of two decades — after moving away when the Balsams closed. One of those complaints came from someone who lived in Couture’s new hometown and recognized him while watching television coverage of the midnight vote.

Couture declined to speak to NHPR on the record, but state files say he was “very cooperative” when told to stop voting in Dixville Notch. That complaint into Couture is ultimately what led to a larger review of Dixville Notch’s voter records for the 2016 election.

Renewed Effort To Revive A Local Institution

As most of the former Balsams employees have moved away, part of what’s kept Dixville Notch’s elections hanging on — by a thread — are the people who’ve moved in temporarily to work on a project to restore the old hotel. And some of those voters have also faced questions from the attorney general’s office.

One of those voters was Nancy DePalma, who said she was living part-time in Dixville Notch at the time of the 2016 election while working on the Balsams redevelopment project.

“I was told the day of the election that I could register for Dixville,” DePalma said. “And I was very excited to do so because, first of all, my right to do so, and the historical value of being first in the nation.”

Developer Les Otten, who was leading the Balsams renovation project, also got a call from a state election investigators questioning his decision to vote in Dixville Notch during the 2016 presidential primary. Otten said he and several of his employees were bunking temporarily in houses on the property of the Balsams resort.

“Last I knew, as a citizen of the United States, I have a legal right to register to vote. So why does anybody register to vote? I wanted to vote in the election,” Otten said. “I owned property. I was sleeping there. So I voted.”

Otten did not vote in Dixville Notch during the 2016 general election because, he said, the Balsams reconstruction project was not moving forward as expected and he was spending more time at his home in Maine.

According to state’s files, Otten told the attorney general’s office in 2017 that he suspected the complaints against Dixville Notch’s elections were at least partially motivated by a desire to “hurt his reputation and, in addition, derail the Balsams project” because of his support for Northern Pass, a controversial energy project. Otten said he stands by that claim today.

“I have an opinion that this is much ado about nothing, but at the same time I know people, some people, think it’s serious — otherwise the attorney general wouldn’t have been looking into it,” Otten said.

Dixville Official Defends Elections As 'Absolutely Trustworthy'

“We don’t think any of these individuals had any type of intent to commit voter fraud. But we don’t believe any of these individuals should continue to claim Dixville Notch as their voting domicile.”

Associate Attorney General Anne Edwards

The state stopped short of charging anyone who voted in Dixville Notch in 2016 with wrongful voting. But based on their findings, the attorney general’s office says most of the people who voted in Dixville Notch in 2016 probably should have voted elsewhere.

“We don’t think any of these individuals had any type of intent to commit voter fraud,” Associate AG Edwards said. “But we don’t believe any of these individuals should continue to claim Dixville Notch as their voting domicile.”

Despite backing off their investigations into all of the voters on Dixville Notch’s checklist, it’s clear the attorney general’s office was alarmed by their initial findings. In February 2017, a state election investigator was so troubled by the situation that he told his colleagues “it might be beneficial and productive to issue subpoenas” to Dixville Notch’s local election officials.

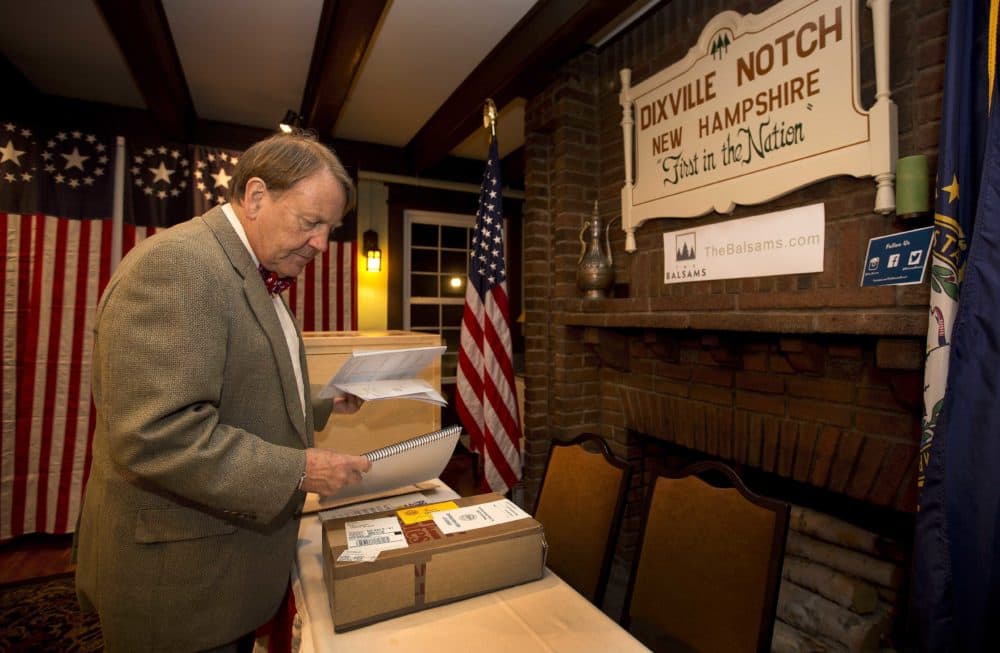

One of those election officials, Dixville Notch moderator Tom Tillotson, said he didn’t realize that the state harbored such serious concerns about Dixville Notch until contacted by NHPR for this story.

Tillotson was aware of the cases involving Peter Johnson and Jacques Couture, but he said he wasn’t fully aware of the extent of the attorney general’s broader investigations into Dixville Notch’s elections.

Those elections, Tillotson said, “have always been absolutely trustworthy.” He has no regrets about any of the voters singled out by the state’s investigations.

“We would be the first to be upset that somebody was actually doing fraudulent voting,” Tillotson said.

Tillotson’s dad, Neil Tillotson, was largely responsible for bringing the midnight voting tradition to Dixville Notch in the first place. In that spirit, Tom Tillotson said his goal has always been to encourage voter participation.

But his encouragement came from as much a practical place as a philosophical one: Under state law, Dixville Notch and other towns that vote at midnight can’t close the polls unless all eligible voters have cast a ballot, either absentee or in-person.

“That's my job — to herd the cattle, herd the cats, to get everybody that's on the voter list here,” Tillotson said.

Whenever Tillotson asked people living in Dixville Notch temporarily if they wanted to register to vote, he said he was just trying to fulfill that responsibility.

Too Small To Vote?

As the state has taken a harder line on who can vote in Dixville Notch, the community is facing another problem: It’s running out of people to staff its elections.

In November 2016, Dixville Notch had eight people on its voter checklist. By last fall, it was down to just five: Tillotson, his wife, his son and two people working on the Balsams redevelopment project. The future of the Balsams project is uncertain, and if it stalls, that could leave just the Tillotson family for next year’s presidential election.

Last month, the attorney general’s office sent Tillotson an ultimatum: At its upcoming local elections in March, Dixville Notch needs to make sure it fills all of the positions legally required to oversee an election; if that doesn’t happen, the state will order Dixville Notch’s remaining voters to cast their ballots in another town.

Dixville Notch needs to find a way to fill seven state-mandated positions in total — some, but not all, of which can overlap. But if that doesn’t happen, all elections in Dixville, including its midnight presidential vote, will have to be put on hold.

“If the tradition needs to end because Dixville doesn’t have enough registered voters to vote, then sadly, the tradition will end,” Edwards said. “They are not the only community who votes at midnight.”

Assistant Attorney General Matt Broadhead, who leads the election law unit, also chimed in: “As far as I’m aware, we haven’t had any issues with Hart’s Location,” referencing one of the other towns that partakes in the midnight voting tradition.

Tillotson is optimistic that Dixville Notch will find a way to fill the seats it needs when its local elections roll around this spring. At the same time, it’s hard for him to ignore, “It’s getting to be a ghost town here.”

Of course, whether Dixville Notch can fulfill its statutory obligations to be able to hold its midnight vote is just one question. Whether the caravan of news trucks keep coming to cover an election that’s essentially just Tillotson and his family — that’s another.

“We'd probably still do it,” Tillotson said. “But it'd be in my living room.”

This story is a production of the New England News Collaborative and originally aired on New Hampshire Public Radio.

This segment aired on February 12, 2019.