Advertisement

Analysis

How Early Voting Data Shows Some Inequities In The Mass. Democratic Primary

Early voting in Massachusetts is a big hit. Out of the record-breaking 1.7 million votes cast this month, just over a million votes were cast absentee, by mail or early in-person, according to data from the Massachusetts Secretary of State’s office. The early vote alone would have been a record turnout compared to any other primary election going back to 1990. But those early votes were not distributed evenly — not by party primary, or geography, or by racial and socio-economic demographics.

Democratic primary voters were far more likely to vote early, as pre-election polling suggested. Nearly two-thirds (65%) of the votes in the Democratic primary came in early, compared to just 38% in the GOP primary. President Trump has been trashing early voting in recent months, and Massachusetts Republican voters appear to be listening.

Within the Democratic primary, the first elections with early voting featured a shift in voting power to whiter and wealthier towns, compared to other recent primaries that did not have early voting. Cities and towns took up early voting at very different rates, with early voting rates ranging from 28% all the way up to 86%. When all the votes were counted, the places with less early voting ended up casting a smaller share of the total votes than they did in other recent primaries, lessening their power and influence in choosing candidates.

These communities are disproportionately low income and home to most of the state’s people of color. While more voters in these communities showed up to cast ballots on primary day, it was not enough to make up the gap in early voting.

These disparities raise questions about whether early voting, which has the potential to make voting easier for more citizens, could actually end up giving further advantage to wealthier and whiter communities, where turnout is already typically higher.

Well-off Boston suburbs and liberal enclaves in the Pioneer Valley provided mostly early voting ballots. The dozen cities and towns where 80% or more of Democratic voters cast their ballots early reads like a who’s who of MetroWest suburbs: Acton (86%), Wayland (86%), Stow (84%), Lexington (84%), Lincoln (83%), Burlington (81%), Sudbury (80%), and Wellesley (80%). In many of their neighboring communities between Route 128 and I-495, 75% or more of Democratic votes came in early.

At the other end of the early-voting list are a mix of tiny towns in rural western and central Massachusetts (where social distancing may have been less of concern), alongside some of the state’s largest and most diverse cities. Among those least likely to cast ballots before primary day were Boston (51%), Quincy (51%), Chicopee (50%), Holyoke (51%), New Bedford (51%), Brockton (48%), Lawrence (45%), and Springfield (42%). On average, the state’s 11 original Gateway Cities saw 52% of their Democratic primary votes come in early, compared to two-thirds of votes from the rest of the state.

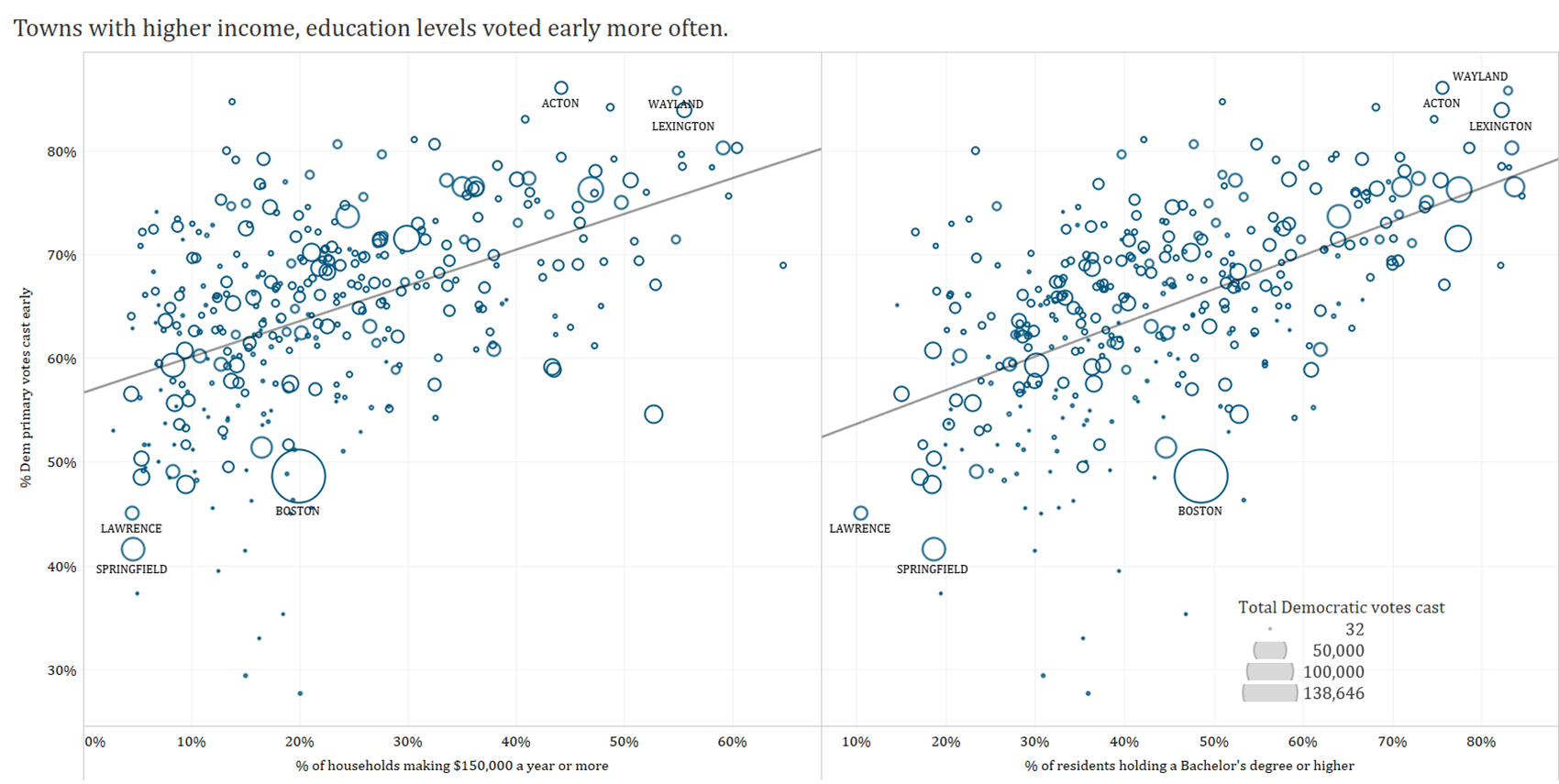

As these two contrasting lists of communities suggests, there are significant demographic differences associated with rates of early voting. Comparing the rate of early voting to town-by-town demographic data from the American Community Survey (compiled by the Metropolitan Area Planning Council’s DataCommon project) reveals disparities by communities’ income, education level and racial make-up.

Overall, there are strong relationships between early voting rates and the income and education levels of each city and town. In the 10% of cities with the highest rates of early voting, 64% of residents have a Bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to just 31% among the bottom 10%.

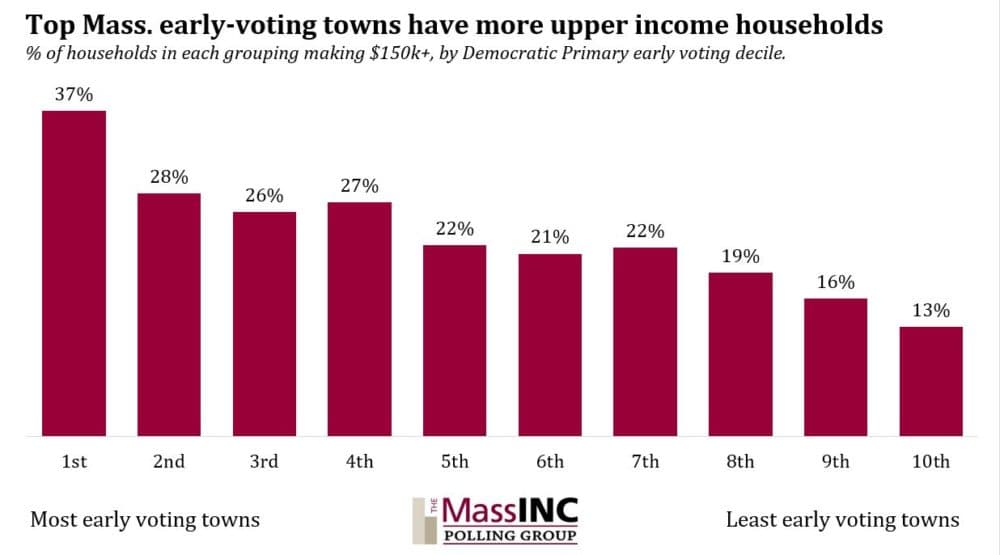

The same pattern holds for income levels: 37% of households in the top early voting towns made $150,000 or more annually, declining steadily to just 13% among the least early voting towns.

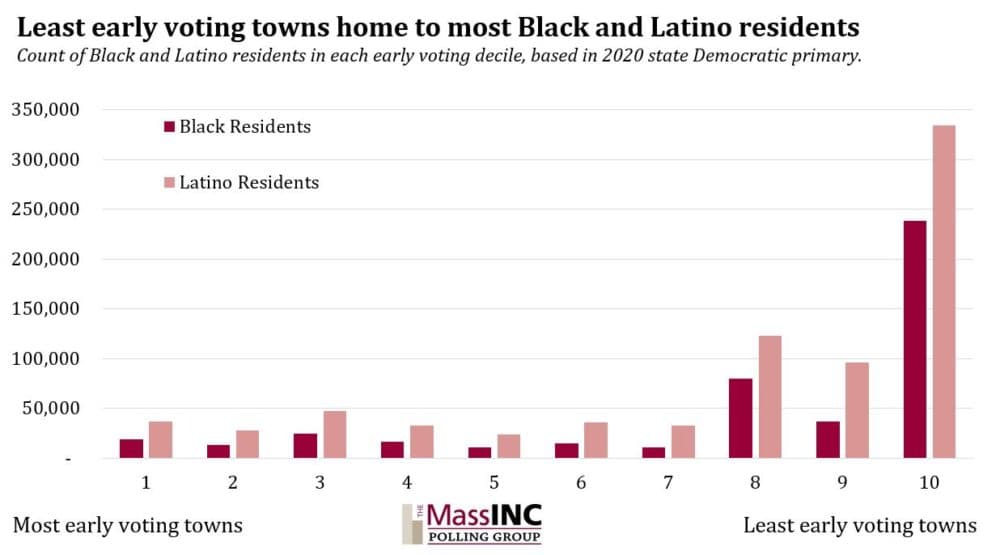

While wealthy towns voted early in larger numbers, most Black and Latino residents live in one of the towns where early voting was least common. Looking at the 30% of towns with the least early voting, a total of 77% of the state's Black residents, and 70% of Latino residents call one of them home.

A shift in voting power away from these cities and towns would represent a diminishing of political influence for people of color in the state’s Democratic party. Even as Democrats discuss ways to address other elements of systemic racism, it's the party’s white voters who appear to benefit from the changes to voting rules.

These town-level demographics suggest that the state's wealthiest, best educated communities took full advantage of early voting, while communities with lower levels of income and education, and with more of the state’s non-white residents, voted early less often. The gap in the early vote was partly, though not fully, closed by primary day. The result was a shift in power toward the towns where early voting was the most common.

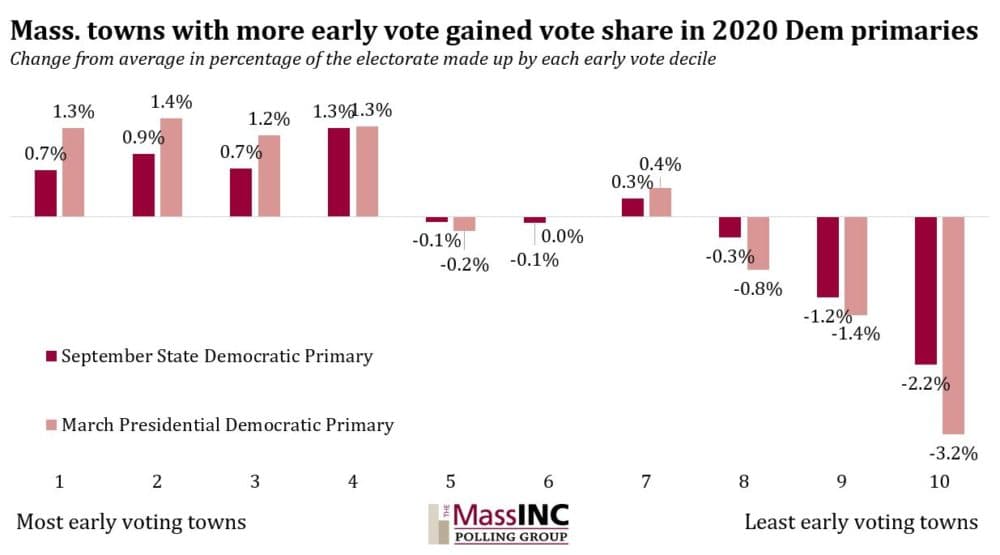

In this month’s Democratic primary, ballots from the top 30% of towns with the highest early voting rates comprised 35.8% of the total votes cast. That’s 2.3 percentage points more than those same towns made up, on average, across seven previous Democratic statewide primaries, which did not feature early voting, going back to 2010.

The bottom 30%, which again includes many of the state largest cities, made up 34.8% of the vote this primary, down 3.7 points from their average in those same previous primaries.

That makes for a net shift of 6 percentage points of the total votes cast — over 85,000 votes — towards the wealthier, better educated towns that took fullest advantage of early voting, and away from big, diverse cities (and other smaller towns) that used it less. Looking at the same 10 groups of early voting towns shows a clear shift in voting power toward towns that vote early in greater numbers.

A few possible caveats are necessary. We’re only a few years into widespread early voting of any kind in the state, and this primary was the state’s first use of widespread mail-in voting. So while there are troubling signs in the voting patterns this year, we don’t know for sure what is driving the shift.

The presidential primary earlier this year was the first Massachusetts primary of any kind with early voting, and it showed the same pattern, with early voting towns gaining in their total share of the electorate. It’s possible that the pattern has more to do with suburban Democratic voters activated by national politics are turning out in larger numbers than they have in past elections.

It’s also possible that the speed with which the state implemented mail-in voting in response to the pandemic favored better-informed voters with more time to focus on the election process. Perhaps better-educated voters were more aware of the changes being made and therefore more likely to use them.

If public knowledge were a factor, perhaps the differences in early voting rates will narrow as voters across the commonwealth become more familiar with the practice. But it is something the Democratic party, and state and local elections officials, will want to consider as they publicize early voting options.

By most accounts, Massachusetts’ first attempt at mail-in early voting went smoothly, despite concerns about the postal service. It’s less clear whether it benefited all voters and all communities evenly and equitably.

It will be worth watching if the patterns that showed up in this month’s primary — with wealthier, better-educated towns making full use of early voting and potentially making up a larger share of the overall electorate — continue in November. If they do, the state may need to think about steps it could take to make sure early voting continues without giving some places and groups more influence in elections than they already have.