Advertisement

'Why'd You Pick Me?': Eyewitness Reforms Offer Limited Help To Those Convicted Decades Ago

Resume

In 2011, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court put together a task force of people from all over the criminal justice community.

They studied how eyewitness evidence is used in the courtroom and offered science-based recommendations going forward.

But it left many people who were convicted before the report still in prison.

'Hocus-Pocus'

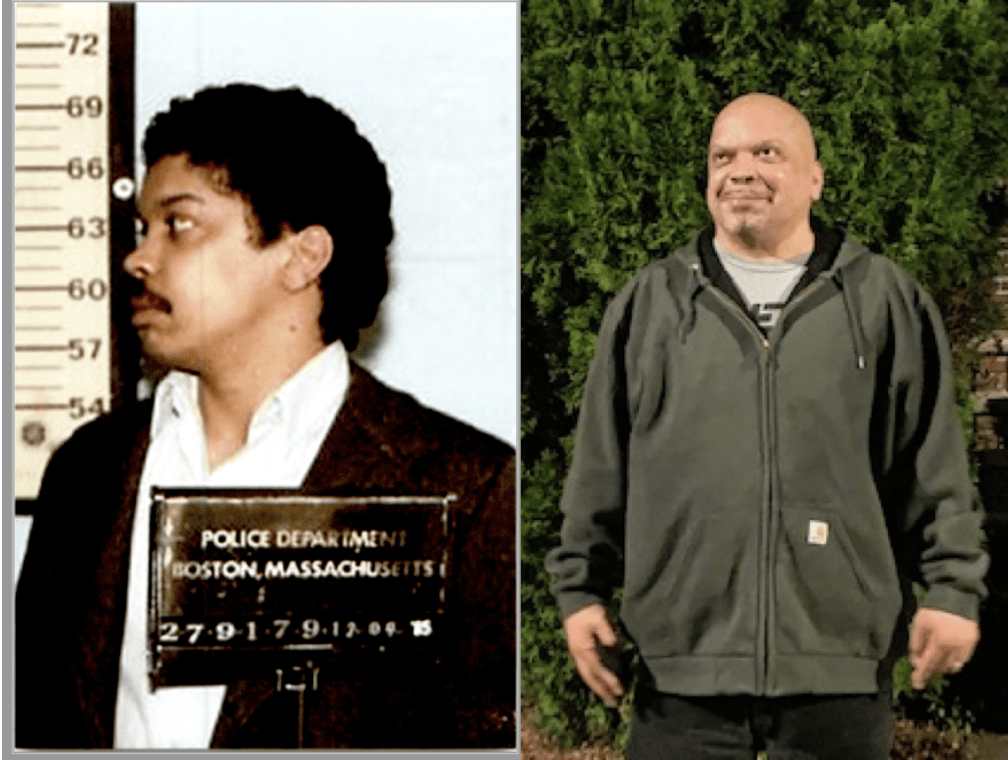

James Watson was 20 years old in 1979 when Boston police officers said they wanted to ask him questions about the murder of a cabdriver named Jeffrey Boyajian.

“ ‘Did anybody hear anything or see anything?’ ” Watson recalled the officers ask. “You know, they knock on people's doors. They knocked on my door. And then they stayed at my door.”

At the time, Watson was unemployed, a new father of an infant son. He told police he knew nothing about the crime. But they said two eyewitnesses saw him get into Boyajian’s cab the night he was killed.

“I said, ‘Give me a polygraph, lie detector test, whatever. And it'll come out, you're focusing on the wrong guy,’ ” Watson said. “They agreed to that [but] it never happened.”

One of the witnesses was another cabdriver named Richard Dwyer, who said he saw, from across the street, at least two Black men get into Boyajian’s cab.

According to records found by Watson’s lawyers years later, Dwyer only picked Watson and his co-defendant out of a photo array the second time he looked at it. And that was after he was hypnotized at the police station.

The NPR podcast "Hidden Brain" found a transcript of the police hypnosis in the case of Watson and his co-defendant, Fred Clay. Here is an excerpt:

Detective Patrick Brady: Now what is going to happen is I am going to turn the channel, and when I do, you begin this documentary. And you will see it clear in your mind. I am getting ready to turn the channel now. When the documentary begins, it will be of you sometime around 4 o'clock this morning sitting in your cab. I am going to slow the frames down now. They're going very slow, slow motion.

Dwyer: I'm scared.

Brady: Scared? There's nothing to be scared of. You're just watching this.

Dwyer: They're going to do something bad to him. They're going to do something. I just don't like them.

Watson’s lawyer, Barb Munro, said hypnosis — at the time — was considered a legitimate way to extract evidence from a witness, as though memories were hidden just under the mind’s surface, in perfect photographic form.

“We know that's not true now, but it's very riveting back then,” Munro said. “And any jury is going to believe that and say, ‘Oh, wow.’ ”

When Watson thinks about this evidence today, he just shakes his head.

“It was bizarre to me," Watson said. "I don't believe in hocus-pocus. That's what that is — hocus-pocus. Something you put in a movie for laughs. Not for life.”

'Why Me? Why’d You Pick Me?'

In addition to the hypnotized cabdriver, there was another witness named Neal Sweatt. He had refused to make any identification during two photo arrays, until, according to court documents, the police promised to move his family out of a housing project.

Like Dwyer, Sweatt was white. Scientists believe cross-racial identification is more likely to be wrong.

According to court documents, Sweatt was also cognitively impaired, with an IQ test score of 58.

“You have somebody who is intellectually disabled looking out a window, at least 75 feet away at 4 a.m. in the morning, and can identify a Black man unequivocally?” Munro said. “That is ridiculous to me.”

Nevertheless, in 1984, after two trials, Watson was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison.

He tried to stay busy there by painting and learning to hang sheetrock, so that he could fall asleep at the end of the day. But most nights he couldn’t stop his mind from obsessing.

“Why me? You know, why'd you pick me?” Watson said. “With all the real bad people out there, you pick me.”

That question is both existential and practical. Why was he picked?

Since DNA started to exonerate people, the Innocence Project has found that 70% of wrongful convictions were the result of faulty eyewitness testimony. A third of those were misidentified by two witnesses.

Watson had been insisting for decades that the witnesses were wrong in his case, but things only started to change about five years ago, when a new set of lawyers took over his case.

“I was just praying and hoping that, you know, this time, something good happens,” he said.

'There's All This Pressure On The Eyewitness To Pick Someone'

Before we go further into Watson’s case, let’s look at what happened to another man, Tommy Rosa.

“In 1993, when he was convicted, there were many things that were told to the jury that were scientifically incorrect about the eyewitness identifications,” said Radha Natarajan, executive director of the New England Innocence Project.

Natarajan is also a lawyer for Tommy Rosa, who was 24 in 1985 when a woman named Gwendolyn Taylor was killed in Boston.

Shortly before the murder, Taylor had come to a friend’s door, in a panicked state, with a man who was threatening her.

“This man, the stranger, was behind her. He was holding a shiny object up to her neck,” Natarajan said. “It was dark. The streetlights actually were broken.”

The two of them left, and the next day, Taylor was found dead. Her shaken friend was asked to come to the police station and look at photos.

“They didn't have any suspects in mind at the time. She said, ‘I think it's a Hispanic man.’ And they gave her mug books,” Natarajan said.

Decades later, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court warned against that kind of photo array because it invites wild guesses. Experts say it’s better to have one actual suspect and at least five fillers who look similar. But back then, Natarajan said, all the witness had to do was pick one of the mugshots and voila — a suspect.

Rosa’s photo was among them because he’d previously been arrested for marijuana possession.

“There's all this pressure on this eyewitness to pick someone ... so that there's some closure, there's some feeling of justice,” Natarajan said.

The witness chose Rosa.

Later, Natarajan said, the witness realized she had seen him at a bus stop.

“And what we know now is that it's so easy for eyewitnesses to make mistakes about where they saw someone,” Natarajan said.

Rules That Look Forward — Not Back

Natarajan believes Rosa’s case shows how poorly the workings of memory were understood three decades ago. Take the role of stress and trauma. The prosecutor in Rosa’s case told the jury the witness was clearly traumatized by seeing her friend with a knife at her throat.

“He actually said it makes an imprint in your brain, in your memory, and you will never forget,” Natarajan said. “That's scientifically incorrect. Trauma actually makes it harder for the brain to create an accurate memory.”

Plus, there was a cross-racial identification, which is shown to be less reliable. The viewing time was short. A weapon was present, which can make it hard for someone to focus on a face. And the prosecution claimed the witnesses’ confidence made it likely they were right, though research shows that’s not true either.

Today, after a 2015 court ruling in Massachusetts called Commonwealth vs. Gomes, the judge must instruct the jury on these scientific principles. But that didn’t help people like Tommy Rosa.

“The court said, you know, we're saying that every case going forward is going to have the benefit of this, but we're not applying this to cases going backwards,” Natarajan said.

That was frustrating to people in prison who felt if the rules had been different during their trials, they wouldn’t have been convicted. But Steven Gagne, a prosecutor for the Northwestern District Attorney's Office, said it’s unrealistic to make the rules retroactive.

“If we judge a case from the 1950s by today's standards, I'm sure most of them would probably not hold up very well with time,” said Gagne, who handles cases mostly in Hampshire and Franklin counties. “Science is always evolving, whether it be the soft sciences like identification or the more hard sciences like DNA and fingerprint ballistics.”

And if cases were constantly being re-examined, he said, “then there's no saying how far back you could go and have cases reopened and victims suddenly getting a phone call saying, ‘Hey, you know that case from 1978? It's been overturned.’ So I think the courts try to strike the right balance.”

That said, Gagne mentioned his office also has a “conviction integrity unit” that looks into old cases where new evidence comes to light that suggests possible innocence.

Although the new eyewitness rules did not apply to old cases, lawyers with the New England Innocence Project and the Boston College Innocence Program took on Tommy Rosa’s case anyway.

Decades after the murder, they tested clothing from the victim, which ruled out Rosa’s DNA. Then they went through all the eyewitness evidence they say should have been questioned at trial.

And in October 2020, after 35 years in custody, Rosa was released — at least for now. A judge allowed Rosa to leave prison while his appeal is being argued, partly because of the risk of COVID-19 behind bars.

“This is awesome!” Rosa told his supporters on the day he was released.

He described the phone call he received when he learned he was going home.

“I got very happy because sometimes you thought this day would never happen,” he said.

'Do Your Job'

James Watson had been in prison for more than three decades before Barb Munro and Madeline Weaver Blanchette took over his appeal, in collaboration with the New England Innocence Project.

Similar to Tommy Rosa's case, they focused on the eyewitness principles that have come to light since Watson was convicted — from how far away the witness was to the use of hypnosis.

“(Today) those identifications would be subject to motions to suppress or to exclude," Blanchette said. "They would be so vigorously cross-examined."

In November 2020, a judge vacated Watson’s conviction and the D.A. chose to drop charges. This was a few years after his co-defendant Fred Clay had already been exonerated.

After 41 years in prison, James Watson was declared free.

“I really can't put it into words,” Watson said from his lawyer’s office, a few weeks after the charges were dropped. “That feeling to just walk down the street when I want to, go into the store, buy a carton of orange juice, and go back to the house.

“Just to be able to walk down the street, with no shackles, no cuffs, nobody tell me, 'You can't go here. You can't go there. Turn right. Turn left. Stand still.' It's amazing.”

Still, it’s hard for Watson to believe, in his heart, that he’s really in the clear. Given how little evidence was needed to lock him up, he doesn’t believe anyone is safe from wrongful conviction — certainly not a 6-foot-5-inch Black man.

“I stick out,” he said. “I was Black, poor, they needed somebody to lock up for this, and they chose me.”

He’s always on eggshells. He still half-expects a visit from the police.

“When I hear about crimes similar or close to it, I just lock my door,” he said. “I'll never get into another taxi as long as I live.”

Does he think the system has improved at all over the last 40 years?

“No. The system is broken. It's broken,” he said.

Watson tries not to be bitter. He’d rather focus on spending time with his son and grandchildren. But he would like to see some things change in the criminal justice system.

“Get more training, actually look into the case,” he said. “Don't reach your hand into a hat and pull out a bunch of names of people that, you know, live in a neighborhood. You know, do your job.”

This is the second in a three-part series, Questioning The Witness — a look at the evolving science of eyewitness testimony and the people with the greatest stake in how it’s used.

___

This story is a production of the New England News Collaborative. It was originally published by New England Public Media on Feb. 16, 2021.

This segment aired on March 1, 2021.