Advertisement

'We Must All Engage:' In New Book, Scholars Offer Advice For White People When Discussing Race

Resume

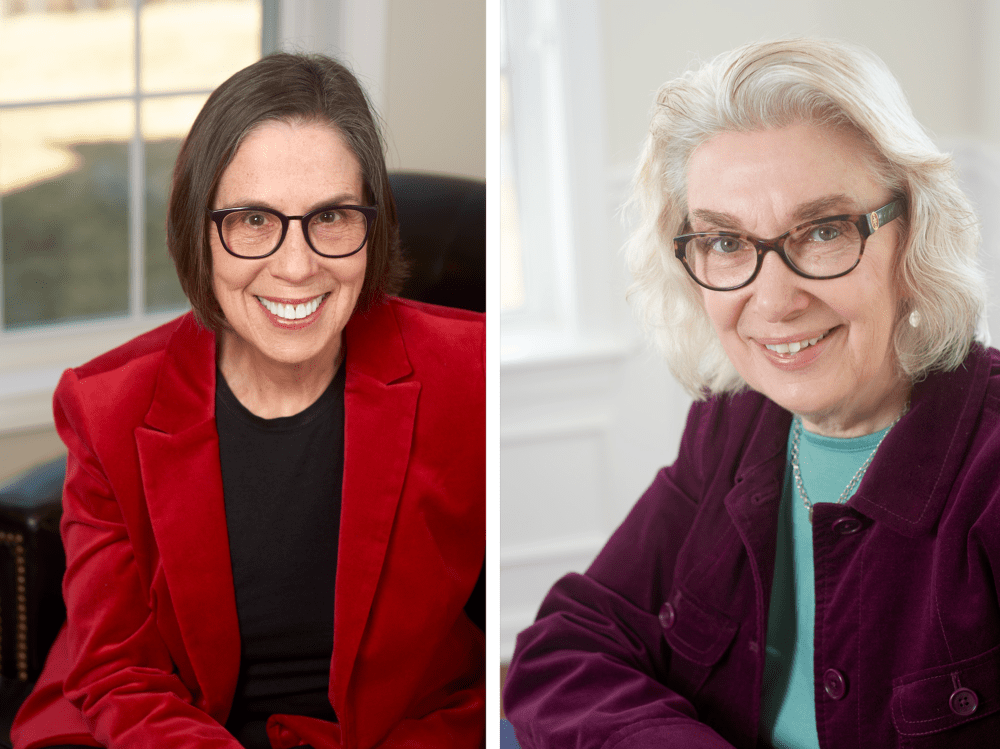

Marlene Fine and Fern Johnson are well-versed in race relations.

They've taught it; Fine is professor emerita at Simmons University, and Johnson is professor emerita at Clark University.

And they've lived it; The women are white, and their two sons — adopted as infants, and now in their 30s — are Black.

Now, they've published a book aimed at getting white people to engage in deeper conversations about race and about the experience of being Black in America. They said the need for that engagement is even more urgent following former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin's conviction in the murder of George Floyd.

"This is not known to most white people, so we have to learn it explicitly," said Johnson. "We have to see it, to confront it, and figure out what to do about it."

The book is called "Let's Talk Race: A Guide For White People."

Interview Highlights

On their first memories of recognizing race:

Johnson (who was raised in a Christian family in Brooklyn Center, Minnesota): "Our street and our whole suburb was white. And I remember that a Black family moved down the street from us. And then it wasn't long after that when ... I realized that they were moving out. And so I had heard my parents talking about a meeting. My dad was going to a meeting about this family. And then ... I kind of started to put it together. And so I asked my parents, 'Why did they move?' I believe it was just my mother who answered the question. And she said, 'Well, they moved because they would really be happier living someplace else. End of story.' "

Fine (who was raised in a Jewish family in New Jersey): "We moved to a community when I was 12 or 13 that was entirely white. And perhaps a year or two after we moved, my father told me that he had been invited to a meeting of other men in the town ... ostensibly about how to keep a Black family from buying a home in the community. My father didn't go to that meeting, but what I can tell you is that no Black family ever bought a house in the town for as long as I lived there and even for the years after I moved away while my parents were still living there."

On starting conversations about race as a white person:

Fine: "One of the first things that we all have to do as white people is simply learn more. And educating ourselves is a starting point. It's also important for us to talk to each other. If we do it with each other, there's a sense, I think, that we can make mistakes and be called to account for those mistakes with each other. We can get a better sense of our own thinking ... we need to refine our ideas before we even start to think about talking across race with Black people."

On what not to say in those conversations:

Johnson: "[A white person saying they've had the same experience with police as a Black person] essentially denies, erases the experience of the Black person ... who has every reason to be afraid and to know that what they are experiencing and why they are afraid isn't the same as it is for a white person. It's experience. That makes the difference."

Fine: "I think there are things that we naturally say to other people in conversation. It's not at all unusual for us to want to relate to and to identify with another person that we're having a conversation with ... [but] when you're talking across race, when [a white person] jump[s] in with 'I've had that experience, too,' you are then saying that the experience of the Black person is somehow identical to yours. And so it is a way of saying to them, 'No, you don't have different experiences,' but the truth is they do.

"I mean, I remember the time that one of our sons was driving up to New Hampshire in a snowstorm. And when he arrived, he called us. His voice was shaking. He was practically in tears. He said that a state police officer had followed him the whole way, both tailing him and then pulling alongside him, staring at him, pulling back. And our son was terrified. He was terrified because he fundamentally believed that that police officer would pull him over and accuse him of something. And he knew that that could get out of control very quickly."

[The officer drove away when their son pulled off the interstate and reached his destination.]

Johnson: "Most of us [who are white] who have driven for a few years or more, we have had experiences where we have spotted a police car behind us. And, you know, it's like, 'Oh, my gosh, I have to slow down, what am I doing' ... it's kind of a panic moment. So it's very easy to say, 'Oh, I've been followed, too. I know exactly how you feel.'

"No. You don't know because it's a different experience, literally ... and the consequences could be very different."

Fine: "[Instead] what I would say is that you listen and you listen closely, attentively, and you say something that demonstrates that you have understood that experience, not in the sense of, "I've had it, too,' but, 'I am hearing you. I understand how serious that was, how afraid you might have been.' "

On making mistakes:

Fine: "We all make mistakes, we make them all the time ... what's important is being able to own up to our mistakes. So if you say something that's hurtful to another person, it's really helpful to have said as a kind of ground rule guideline in your conversations that it's OK for the other person to say ... 'That really hurt.' And for you to then say, 'Oh, can you tell me why?' And then to really listen to what the other person has to say, and be willing to say ... 'I'm sorry that I said that and I will work not to do that again.' "

Johnson: "Or [say] 'I'm going to say something now. It might be wrong. Please correct me if I'm wrong' ... keep the conversation going rather than fall into silence."

Fine: "I think it's also important for all of us [who are white] to understand that sometimes people will be hurt and will walk away, that they won't continue to engage you. And we have to accept that ... and be able to say, 'OK, but that doesn't mean I'm going to stop wanting to engage in talk about race because it is simply too important.' We must all engage in this conversation."

Authors' recommendations for further reading:

- "The Fire Next Time," James Baldwin

- "The Yellow House: A Memoir," Sarah M. Broom

- "Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents," Isabel Wilkerson

This segment aired on April 22, 2021.