As Sea Levels Rise in Boston, Stormwater May Have Nowhere To Go

Even the experts agree: no one wants to think about the sewer system.

“Most people, all they care about is you flush the toilet, it goes away. You do the sink, it goes away. The water comes out, the water turns off. It rains, the water goes away. As long as it's gone, nobody thinks about the pipes and the maintenance and all that stuff,” said Charlie Jewell, director of planning at the Boston Water and Sewer Commission.

But Jewell thinks about this stuff. A lot. So does everyone at the Boston Water and Sewer Commission, the city department that ensures clean water comes out of the faucet, wastewater goes to a treatment plant and rainwater doesn’t flood your street.

For the most part, Boston’s sewer infrastructure works pretty well. But as climate change causes sea levels to rise and brings more intense storms with a lot of rain, the stormwater system is going to be in trouble. The labyrinth of underground pipes that collects rainwater from catch basins on the street and conveys it to rivers or Boston Harbor isn’t equipped to handle the amount of rain coming our way.

“The pipes are designed to carry a certain capacity, and if the rain is coming so hard and so fast, they can't convey it fast enough,” Jewell said.

The city’s stormwater system can handle a rainstorm that drops about 5.15 inches of water in 24 hours. In the future, we could get that amount of rain — or more — in a few hours.

The commission, like the city as a whole, has been concerned about climate change for years, but the real wake-up call came in 2017, when Hurricane Harvey barreled into the Gulf states. The powerful Category 4 hurricane made landfall near southeastern Texas and then stalled out. It rained for four days, dumping record-setting amounts of water and causing the worst flooding in Houston’s history.

“Who would have thought about 60 inches of rain? That was just unprecedented,” Jewell said.

Houston is a sprawling city with a lot of concrete and other impervious ground cover. Unable to soak into the earth or drain from the sewer system into the already-overflowing rivers and bayous, the rain pooled in the streets. At least one-third of the 669 square mile city was under some amount of water and 3.7 million people had to evacuate.

While the country watched the disaster unfold, then-Mayor Marty Walsh was thinking about the implications for Boston. He called a meeting with representatives from emergency management, the environment team, first responders and the water and sewer commission to ask what would happen if Boston got hit with a similar storm. What major roadways or pieces of critical infrastructure would flood? How would we evacuate people — could we even evacuate people?

By 2017, the city had detailed climate change projections that showed where sea-level rise and storm surge would have the greatest impact. But none of the models really took precipitation into account; specifically, how the city’s stormwater infrastructure would respond to a big storm that dumped a ton of rain at high tide.

Aware of this modeling shortfall, John Sullivan, chief engineer of the Boston Water and Sewer Commission, directed his team to start work on it.

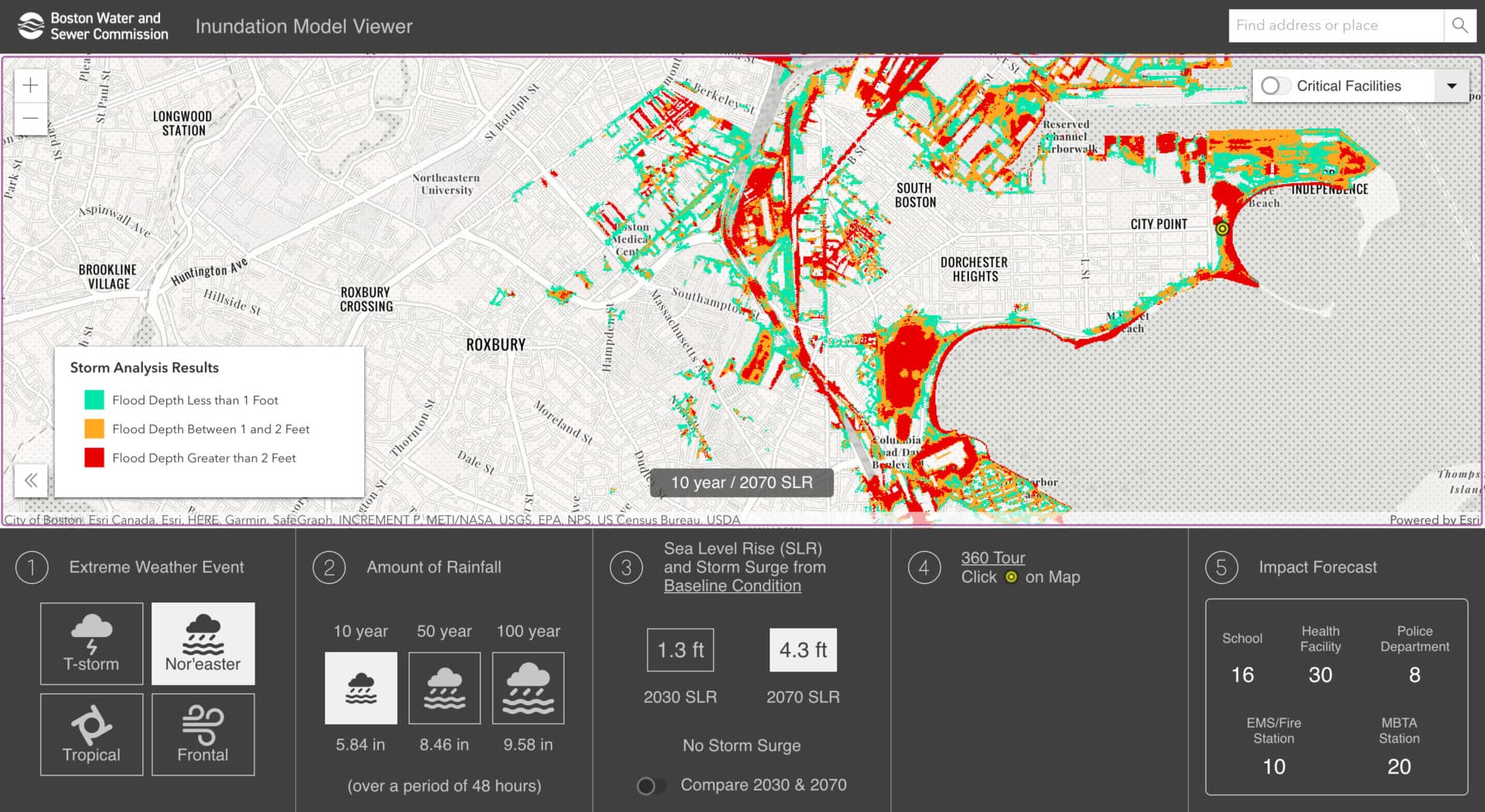

The result was the city of Boston Inundation Model, an interactive website published in 2020 that allows users to choose from a variety of storm and sea-level rise scenarios, and see the impacts. The model uses over 70 years of rainfall data, meteorological reports from 3,100 storms and the most up-to-date climate change information to predict, for instance, just how high the flood waters around the New England Aquarium would be if a nor’easter hit the city in 2070 and dropped over 3 inches of rain in six hours. (The answer: at least 3 feet deep.)

Sullivan was alarmed by the results. Many people knew that stormwater flooding posed a big problem, but now they had granular maps showing the true extent of the issue.

Through its Climate Ready Boston program, the city is already looking at where it may need barriers or flood gates to protect neighborhoods from sea-level rise and storm surge. What the commission needs to do, said Jewell, is "make sure that we maintain our capability to discharge stormwater during a major event.”

In other words, when people talk about climate change in Boston, they often focus on rising seas and how to keep ocean water from getting in. But in the not-so-distant future, an equally important question arises: during a big storm, will the city also be able to get rainwater out?

Ellen Douglas loves to think about the complicated world of pipes, drains and other infrastructure that exists under our feet.

“I’m an engineer, and engineers tend to be interested in the things that other people don't like to look at,” she said with a little laugh.

I always laugh when I drive through Boston and I see one of those hurricane evacuation signs because you can't get out of Boston on a normal day

Ellen Douglas

Douglas, a professor of hydrology at UMass Boston, is one of the region’s foremost experts on climate change and water. And ever since the so-called Mother’s Day Storm in May 2006 flooded her basement with 2.5 feet of water, she’s had a soft spot for studying stormwater. At the time, most of her work focused on salt water, but as the storm raged outside, she began looking at data about rainfall on her computer.

“I wanted to understand what was going on,” she said.

And what is going on, at least here in Boston, doesn’t look good.

In addition to slightly higher average annual rainfall totals, the Northeast has seen a dramatic rise in the amount of precipitation falling during sudden, intense storms — since 1958, there’s been a 70% increase in the amount of rain during big storms. In the future, climate change models show there will be even more runoff pouring into the stormwater drains in a shorter period of time. According to Climate Ready Boston, 7% of the city could experience stormwater flooding by 2050 on a fairly regular basis.

“The capacity of the system is going to be exceeded and it's going to back up and flood people's basements like mine,” Douglas said.

Think of the whole stormwater system — the streets, the metal grates by the curb known as catch basins, the underground pipes and the outfalls that drain rainfall into Boston Harbor — like a funnel under your kitchen faucet.

“As long as the flow coming out of the faucet is not greater than the flow that can come out of the end of the funnel, everything will be fine,” Douglas said. “But if you increase the amount of water coming out of that faucet, eventually you're going to have water overflowing the funnel. That's exactly what happens in a storm drain system.”

And that’s before you factor in sea-level rise and storm surge.

The capacity of the system is going to be exceeded and it's going to back up and flood people's basements like mine.

Ellen Douglas

Without some sort of manual pump, it’s hard to get stormwater to drain from a pipe into, say, Boston Harbor when the harbor water is higher than the outfall pipe. That’s because the harbor water acts like a thumb at the end of the funnel’s tube. The higher the harbor, the stronger the pressure pushing against stormwater trying to drain. In some cases, the harbor water can actually push stormwater back into the system and out through catch basins onto the street. (The city has installed automatic tide gates on some pipe outfalls to keep seawater out during high tide. But since those also prevent stormwater from draining when closed, the backflow problem persists.)

With this in mind, it's easy to understand why the worst-case scenario is a big storm that drops a ton of rain quickly during high tide. It’s a recipe for flooding, road closures and other associated public safety or health issues. And as sea levels rise, it will only get worse.

“I always laugh when I drive through Boston and I see one of those hurricane evacuation signs because you can't get out of Boston on a normal day,” Douglas said.

“When they make these predictions of what's going to happen — this is happening now,” said Maria Lyons, a teacher, climate activist and a life-long resident of Dorchester.

Lyons lives in the Port Norfolk neighborhood, a small peninsula east of I-93 that juts into the Neponset River. With only two streets in and out of the neighborhood, Port Norfolk is a quiet place with a good sea breeze where you can almost forget you’re in a big city, she said.

But for all of the area’s perks, it’s on the front lines of climate change. In 2018, for instance, both roads to Port Norfolk flooded out when Boston got slammed by two nor’easters.

“I was at school for one of those storms and I couldn't go home for hours. I had to wait it out until the water came down again,” she said. “The other storm was overnight and we couldn't leave. We were in our house and we couldn’t leave. So it completely cuts off our neighborhood when it floods.”

Though most of this flooding was the result of storm surge, Lyons said it’s pretty common for low-lying areas in Dorchester to flood after a big rainstorm. (If you've ever tried to drive along Morrissey Boulevard during a downpour, you know what she’s talking about.)

Those closures aren’t just inconvenient, she said. They're a source of great anxiety for her and her neighbors who have seen firsthand what can happen.

Years ago, while one of the two roads into Port Norfolk was closed for construction, an older man on her street had a heart attack. His wife called 911 and the ambulance driver mistakenly went to the closed entrance and had to reroute.

“So it took them an extra long time to find the way to go and to get to the poor man, and he died,” Lyons said. It’s impossible to know if her neighbor would have survived had the ambulance arrived 10 minutes earlier, but for Lyons, it’s hard not to wonder.

To this day, people in Port Norfolk still talk about this incident every time a road in the neighborhood floods, she said.

When they make these predictions of what's going to happen — this is happening now.

Maria Lyons

The ability to get emergency services to people, or to evacuate neighborhoods during a flood, is top of mind for city officials as they plan for climate change. So is equity.

“No one wants to experience a flood, but especially when it comes to stormwater, those who are already vulnerable in the city of Boston become more vulnerable,” said Sanjay Seth, Boston’s climate resilience program manager. People with less economic stability have a harder time recovering from a flooded basement or vehicle, he said. And even the consequences of a so-called nuisance flood, which can shut down a major transit route like Morrissey Boulevard for a few hours, can feel more extreme.

“When you think about a one- or two-hour disruption where water is pooling up on a road and you can't use it, even that can cost millions of dollars in lost time” and wages, and it can cause huge amounts of “frustration and complexity” if it messes up your work or childcare schedule, he said.

“It's the worst-case scenario that really calls our attention, but there's also work that we do to make sure that we think about the everyday as well.”

The problem of stormwater flooding isn’t unique to Boston, but it’s one of the few coastal cities making a plan to deal with it.

On a recent weekday morning, Ben Agrawal and Madison Gleason, two engineers with Hazen and Sawyer, a local consulting group that focuses on water infrastructure, fiddle with a sleek, black 360-degree camera sitting atop a tripod. The camera is about the size of a candlepin bowling ball and, with two antennas sticking out of the top, bears a striking resemblance to an alien.

Agrawal and Gleason position the camera on the side of a small bridge overlooking a muddy creek near Neponset Circle in Dorchester. To their back, the mid-day traffic of I-93 roars. Gleason hits a button and the camera begins humming. It lets out three loud beeps and then a long shutter click. Similar to the cameras Google uses for its Street View maps, this little machine could play a big role in helping Boston resolve some of its stormwater problems.

As Gleason repositions the camera in another location, Agrawal points upstream to another bridge with a big round opening.

“Right over there, that's the outfall itself where the stormwater comes out,” he said.

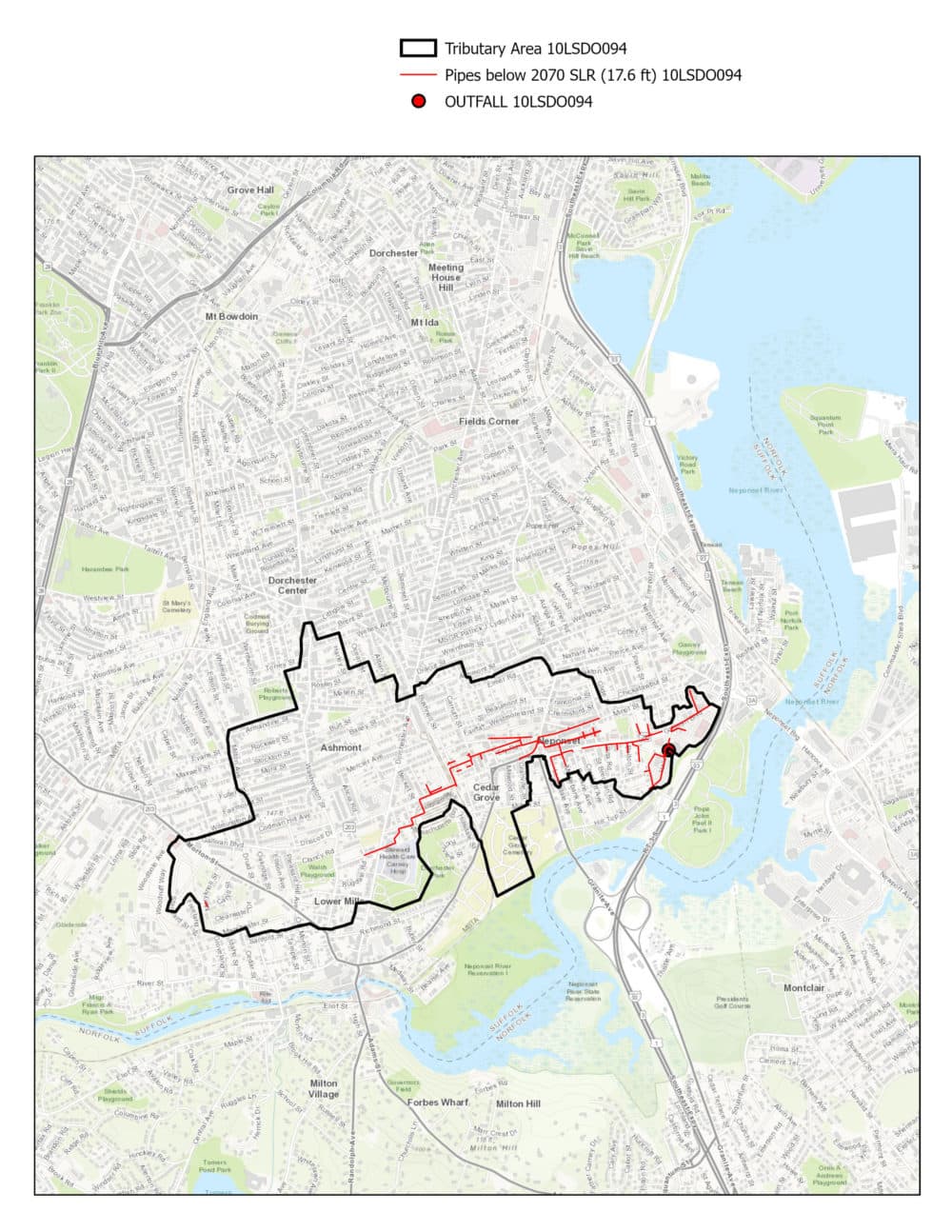

Rainwater runoff from parts of Neponset, Cedar Grove, Ashmont and Lower Mills — home to about 12,800 people — flows out of this 72-inch pipe into the creek. From there it travels under the highway into the Neponset River and eventually makes its way to Boston Harbor.

“If water could not get out of that [outfall] right there, it could back up into the system,” he said.

He pulls out his iPad and calls up a map that shows the outline of the drainage area and the outfall. There are stormwater pipes running underground throughout this area, but “these red lines right here,” he said, pointing with the tip of his pen, “show pipes where the bottom of the pipe is below what the high tide level could be in the future. And so you can imagine that's the whole area that could be influenced just by high tide.”

The thumb at the end of the funnel.

Add an intense rainstorm to the mix, and those areas with red pipes are going to have some serious stormwater flooding.

The city of Boston oversees 208 stormwater outfalls, 40 of which, including this one in Dorchester, have been identified as particularly vulnerable to flooding. The team from Hazen and Sawyer are gathering data about those locations this summer.

In addition to taking photos, they’re looking at topography and land use, and will overlay that information with maps of underground pipes and the number of affected people and businesses in the area. They'll plug all this information into powerful computers to see how different solutions could work.

Some places may need powerful pumps to force stormwater into the Harbor. Others could get huge underground tanks that can store rainwater during high tide. And for those with no clear engineering fix, the city could try adding more green spaces or planting trees to help soak up rain water.

“Each site is different,” Agrawal said. And as the city prepares “to protect the shoreline from sea level rise, we want to make sure that the sewer system can still discharge stormwater” in critical locations.

The process is still in its very early stages, but sometime next year, the engineers hope to present the commission with several potential plans. From there, city officials and the public will weigh in, budgets will be drawn up and, as Chief Engineer Sullivan said, hopefully the plans will start to get implemented.

“Next time you look at a street, just try looking at it as a conveyance for water, and it really changes how you just think about what all is a part of the storm water system,” said Seth, the city's climate resilience program manager. “It's our streets. It's our parks. It's our parking garages. It’s such an intricate system that's totally hidden from us. But without which we really couldn't have a city.”

Climate change is coming to Boston — in fact, it’s here already. And when it comes to stormwater flooding, the city has been relatively lucky so far. Hurricane Sandy hit us at low tide; the January 2018 nor’easters brought more snow than rain.

But luck isn’t a long-term solution.

The stormwater system may be something people don’t think about, but if Boston wants to remain a liveable city for the next hundred years, it has to figure out what to do with the water coming our way, and it has to do it quickly.

This segment aired on June 17, 2021.