Advertisement

5 Takeaways From Coastal Flooding Report On Martha’s Vineyard And Nantucket

A few years ago, the nonprofit Trustees of Reservations asked a consultant to look at erosion and flood risk at their coastal properties.

The Trustees is — somewhat surprisingly — the largest private coastal landowner in Massachusetts, and their properties had been experiencing unprecedented flooding due to climate change. The organization wanted to see what was ahead.

The consultant's report was eye-opening, said Tom O'Shea, managing director of resources and planning for the Trustees, showing many of their properties at risk.

"This is really a major issue not only for the Trustees, but for coastal communities in Massachusetts," he said. "As an organization that's part of 25 different coastal communities, we thought this was an important time for us to really help lead, and be a voice on coastal resilience."

The group started to take a more active role in analyzing the effects of climate change on the Massachusetts coast and investigating possible solutions.

One of their most visible efforts came in 2020 with their first "State of the Coast" report, focusing on the North Shore; it continues with the release of their new report on Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket, which have some of the highest erosion rates in the state. The islands "are the ones that could be leaders in showing the rest of us how to cope with coastal change," O'Shea said, "because they're the ones who have to deal with it."

Here are the top five takeaways from the new report:

Sea-level rise and coastal erosion is speeding up; flooding will be common on the islands by 2050.

Virtually every resident and visitor to the islands will see the effects of sea level rise by 2050, whether in decreased property values, eroding cultural and historic sites, ferry cancelations, impassable roads, or private wells flooded with salt water.

"We're seeing that now, where the beaches are rolling over on the public roadways," O'Shea said. "The beaches are rolling over onto ponds. I mean, we've seen ponds completely buried by sand. They're marching landward."

Nearly 800 structures worth more than $4.6 billion — including homes, businesses and infrastructure — are at risk of being lost by 2050 to erosion. More than 44 miles of roads are also at risk.

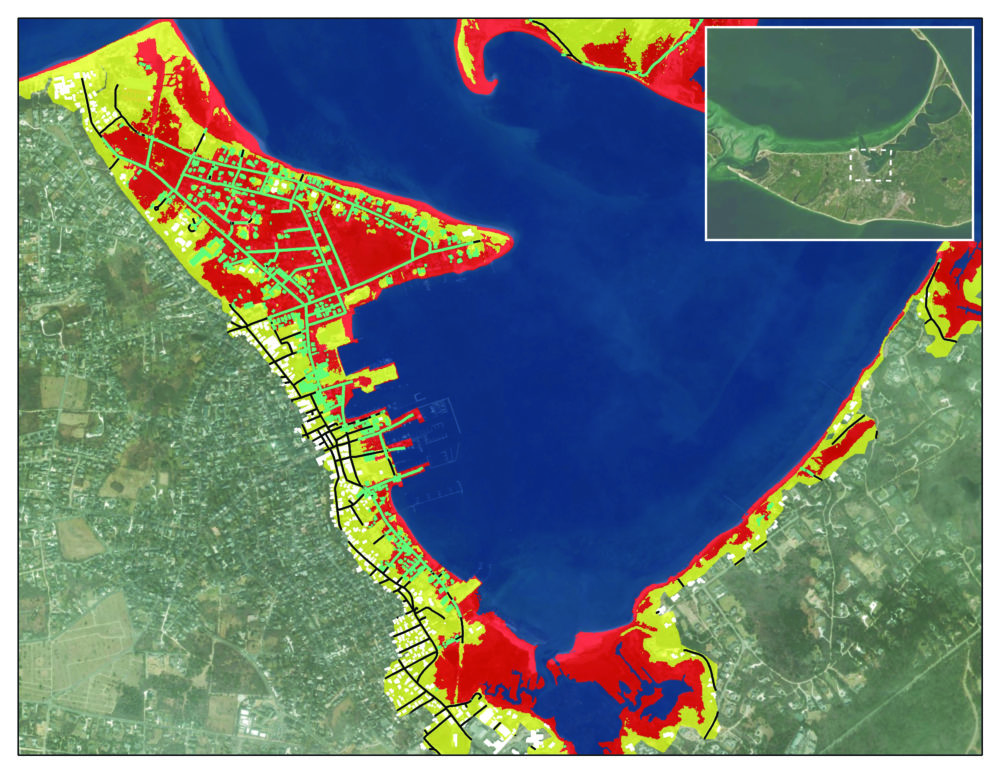

Roughly 900 structures on Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket may experience daily flooding from tides in 2050.

Roads and buildings aren't the only things in trouble: beaches, salt marshes and bluffs are disappearing.

Island beaches experience some of the highest erosion rates statewide, from both storms and sea-level rise but also from storm surges. Martha’s Vineyard beaches have lost more than 1,400 acres since 1897 — and Nantucket, nearly 1,900 acres.

One example: Norton Point, a 2.5 mile barrier beach on Martha’s Vineyard, lost 74 acres over 97 years, from 1897 to 1994. But in the 30-plus years after that, the beach lost 93 acres — or 25% more land in a third of the time. The beach may be open ocean by 2070.

Salt marsh is also disappearing. By 2050, Nantucket could lose nearly 569 acres of high salt marsh — an area 11 times as big as Boston Common, according to the report. But sandy bluffs may be the most vulnerable. For example, Gay Head Cliffs is eroding at a rate of almost 3 feet per year.

The most worrisome areas at risk are harborfronts.

Most people get to the islands by boat, and towns like Nantucket Harbor and Vineyard Haven are hubs of island life.

"Those harborfronts are where people connect; where supplies, food, medical equipment, you name it, come in. The economies are tied to those harborfronts and they are low-lying elevation areas that are going to see more and more flooding," O'Shea said. "They are going to have to figure out, 'How do we have contingencies to continue to keep our economy running and get in and out of these islands?' They know this — it's just that now is the time we've really got to think about it."

Sorry, billionaires, you (probably) can't buy your way out of this one — at least not forever.

On Nantucket, the median home value is over a million dollars, and median household income is more than $107,000. So some rich folks may just pick up their mansions and move inland. The report describes a couple on Nantucket who paid $1.6 million to move their house back from Pocomo Head bluff, and some homeowners on Martha’s Vineyard who moved their 8,000-square-foot home inland after seeing 20 to 30 feet of Wasque bluff wash away in one day.

But these extreme strategies are not going to work forever, and certainly not for everyone. Even if you have money to burn, only a reported 8.6% of land is available for development on Nantucket, and about 10% on the Vineyard, so your house (or your shop) may be stuck where it is. As the report says, "wealth is no match for water." The key to surviving on the islands may be learning to live with a lot more of it.

Embracing the water could be cool! And there are already some success stories. But no matter how you slice it, some hard choices lay ahead.

The nonprofit ReMain Nantucket sponsored a design challenge in 2021, asking creative teams to reimagine the Nantucket harborfront. The teams came up with some pretty cool ideas: boardwalks that double as deployable barriers; front lawns that work as water basins; "sponge parks" and marine gardens.

Nature-based solutions are also gaining traction. Restoring eelgrass beds, for instance, not only helps stabilize sediment, it also provides nursery habitat for shellfish, removes pollutants and sequesters carbon. Preserving and restoring salt marsh will help slow coastal erosion and protect developed areas from storm surge. There have already been some success stories — a large group of collaborators installed the largest living shoreline restoration project in New England at Felix Neck Wildlife Sanctuary to protect marshes at Sengekontacket Pond.

But successes like this will remain one-offs without a comprehensive plan and a lot more funding, O'Shea said.

"Right now there isn't a grand strategy saying how are we dealing with this across the entire shoreline, not property by property by property," said O'Shea, who sees some hard choices ahead for the islands.

"At some point, we have to say, 'What is our strategy with managing our beaches, with living with shorefront property? Are we going to adapt in place or are we going to relocate and retreat? Which beaches do we protect?'

"The scale of it is too big to address everything equally, and so we have to make priorities," he adds. "You have to make choices."