Advertisement

Coronavirus Coverage

mRNA Was Supposed To Stay Ahead Of Variants. Why Aren't We Using Its Full Potential?

Resume

Part of the exciting promise of modified mRNA technology that built Moderna and Pfizer’s coronavirus vaccines was an assurance against variants that might one day evade the vaccines’ protection.

If any troublesome mutations arose, researchers said, manufacturers would be able to reprogram the string of genetic code inside the vaccines to counter that.

Manufacturers have indeed created shots updated for the delta variant, says Dr. Dan Barouch, an immunologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center who worked on the Johnson & Johnson vaccine. Delta has quickly become the dominant strain in the U.S., and it appears to spread even among fully vaccinated people. So, you might think it would make sense to start distributing shots tailored to the delta variant's genome.

And yet, at the moment, vaccine makers are still cranking out their original formulas for new inoculations and the booster shots that the Biden administration plans to authorize in September.

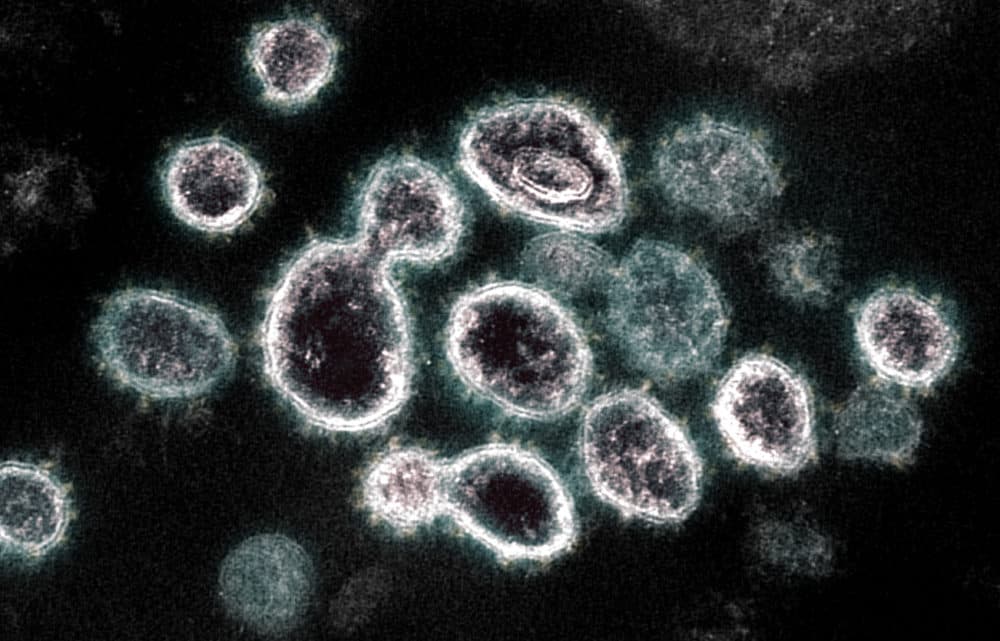

These vaccines contain a string of genetic letters that shows the body's cells how to create the spike protein, which the coronavirus uses to attack human cells. The immune system can then build antibodies that can target and neutralize the spike protein. In the original vaccines, this genetic code was developed using the genome from the coronavirus that first sparked the pandemic. Updated vaccines could use the genome from the delta variant, rather than the ancestral coronavirus, and generate antibodies that are theoretically better at fighting delta.

Except — they probably wouldn’t be much better, Barouch says.

That’s because the delta variant’s spike protein isn’t that different from the elder coronavirus in shape and appearance, so it’s still vulnerable to the antibodies that the vaccines create. Instead, Barouch thinks the reason why delta is able to cause so many breakthrough infections has more to do with its “hyper infectiousness rather than its intrinsic ability to evade antibodies,” Barouch says.

Compared to the ancestral variant, the delta variant tends to cause people to gush with viral particles. That means if you are exposed to delta, you’re likely exposed to a great deal more of the virus, and you’re more likely to get exposed in the first place thanks to the variant’s high infectiousness.

“If you’re exposed with a lot more virus, then the chance the vaccine will protect you is lower,” Barouch says. “And if you go to a crowded venue with many people in a closed space, you might be exposed not once but maybe 10 or 100 times.”

There are also public health and economic considerations that may explain holding off on a new vaccine. There are currently millions of COVID-19 vaccine doses in the U.S. going unused. Suddenly switching to a new version of the vaccine might increase the chances those doses go to waste, says Dr. Benjamin Linas, an epidemiologist at Boston University.

“I don’t know what message it would give if [Pfizer or Moderna] said, ‘Oh we have a specially engineered vaccine for delta.’ Would that generate concern that the original vaccine didn’t work? Which is absolutely not true. These vaccines still work,” Linas says.

Data from the U.S. show the vaccines remain very effective at preventing the most severe outcomes: hospitalization and death. And studies from Israel suggest that giving a third shot of the current Pfizer or Moderna vaccines does help with the delta variant and further reduce hospitalizations, severe illness and death, says Bronwyn MacInnis, a genomic epidemiologist at the Broad Institute. She argues it may not be worth the effort to rebuild the country's vaccine supply with shots re-engineered around the delta genome.

“Given the current vaccines still work and boosting with them seems to help, it may make more sense to continue to go with the bird in hand, and possibly leverage the reprogrammability of the mRNA [vaccines] for future threats,” she says.

After all, the ability to re-code the vaccines is not going away, MacInnis points out. If another variant pops up that does make the current vaccines obsolete, it might be better to incur the cost of revamping the vaccine for that new danger, instead of one that the current vaccines can already defeat.

This segment aired on August 27, 2021.