Trees: Our Mental, Physical, Climate Change Antidote

There are many sugar maples along the banks of the Mill River in western Massachusetts. But this one is special, at least to Danielle Ignace. Its wide, green canopy keeps Ignace cool as she works or entertains friends, even on this hot summer day in Williamsburg. Its tens of thousands of leaves, rustling in a breeze, produce air that is moist and fresh. Its shade, she says, calms her nerves.

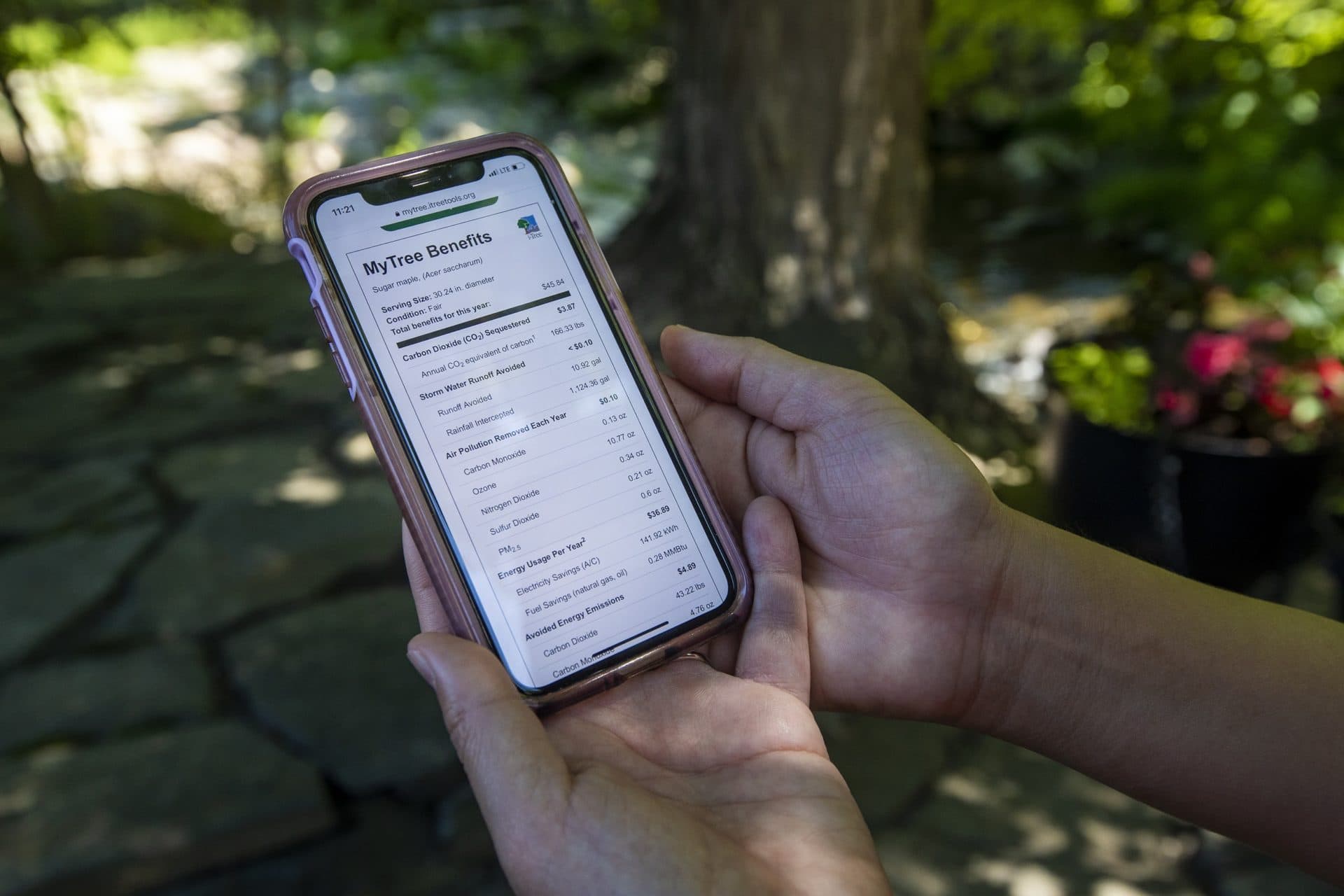

And this sugar maple is a carbon sucking, storage machine. Ignace, an assistant professor of forestry at the University of British Columbia and a Harvard Forest research associate, has just made some calculations using an online tool.

To date, it shows Ignace’s tree has stored 22,049 pounds of carbon dioxide or CO2, one of the main greenhouse gases that is warming our planet. That’s the amount of carbon released by 1,100 gallons of gas burned in an average car.

“That’s quite a feat for a single tree,” says Ignace, grinning.

The hunt for fast, high-tech ways to slow climate change is even more urgent after the release earlier this month of an international report that shows the planet is warming faster than expected. Many experts say the report is also a call to make better use of the tools we already have along our streets, in our yards, parks and forests: trees.

It can be hard to find hope in the face of climate change, but trees are a place to start. What's more, the oaks, maples, beeches and pines many of us take for granted may be delivering countless health benefits, too, from lower anxiety, to better child development and stronger immune cells. Those benefits are a boon for people who live near or among trees. Those who don’t lose out.

Ignace’s sugar maple is hard at work on this summer morning. Much of that starts in the leaf Ignace has just spread across one hand.

Health Care For The Planet

The leaf takes Ignace back to a childhood playing in the woods. In the maple leaf, she saw the shape of a heart. How, she wondered, did the deep green turn fiery orange or red?

There’s a second tree rooted in Ignace’s early memories, the Douglas fir. Its majestic peaks spread across the Coeur d'Alene reservation in northern Idaho, where she’s a member of the tribe. It was there that her father was once a firefighter, on duty to protect Douglas firs.

“I’m just realizing perhaps that was always ingrained in me from my father and how important those forests were,” Ignace says.

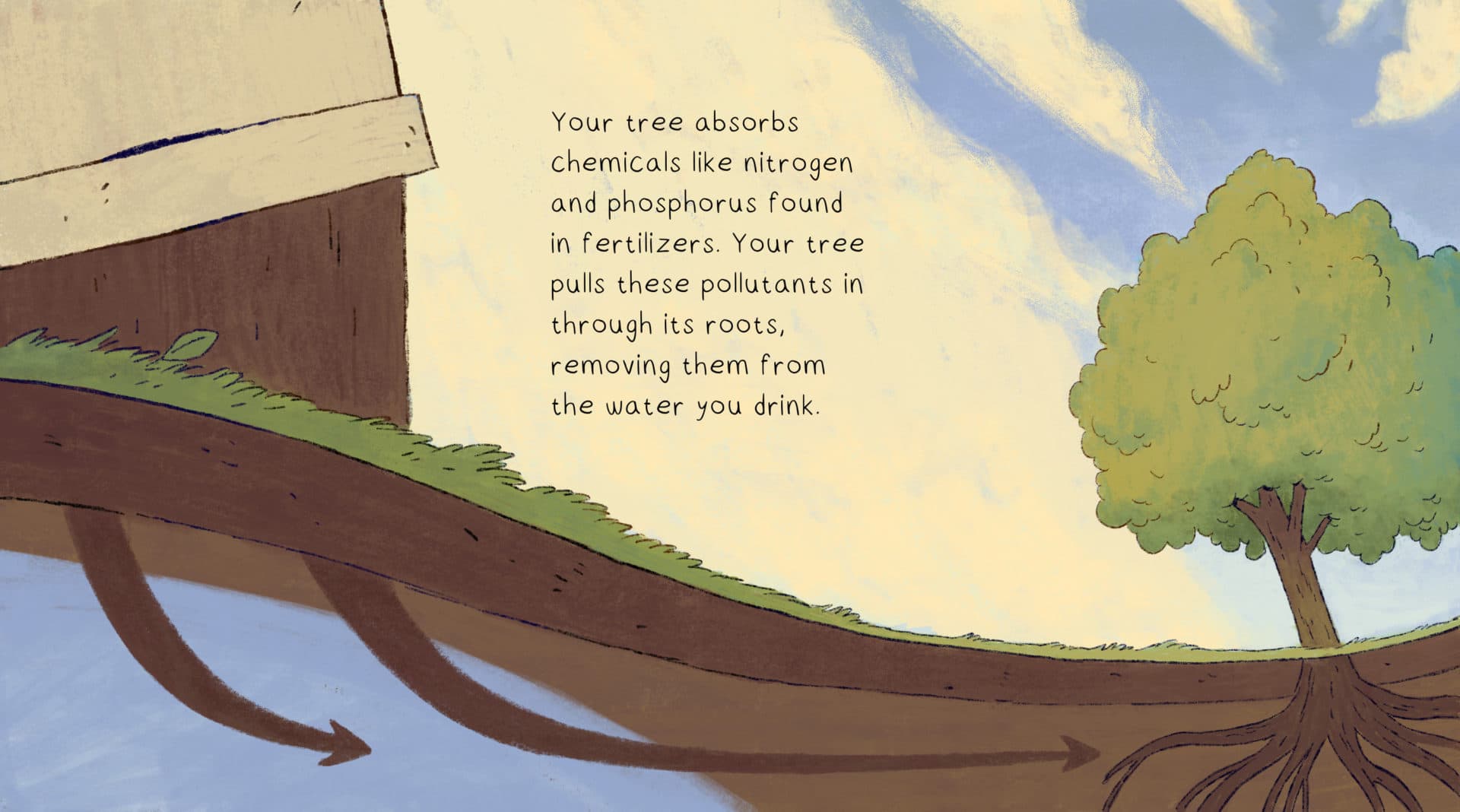

Now, as a scientist who studies trees, Ignace appreciates the beauty of her leaf’s natural hardware. Take, for example, the way it cleans our air. The surface of this maple leaf is covered with tiny pores that open to pull in carbon, ozone and other pollutants.

“Plants are amazing air filters,” Ignace says. “And leaves themselves can capture particulate matter as well.”

Those are the tiny flecks of chemicals and debris that can inflame our lungs. Many get caught on the fibers of a leaf instead, as pollution moves through the air.

The thousands of leaves on Ignace’s vast maple are also mini air-coolers. Trees pull water up through their roots and send it out into the leaves. The millions of leaf pores release tiny puffs of water vapor.

“Not as good as an air conditioner,” says Ignace, laughing, “but I’ll take it on such a hot day.”

Amid all that cleaning and cooling, this maple is also performing a feat science is struggling to recreate —it’s a carbon-guzzling stockpile. Its leaves aren’t just removing carbon from our air, they’re holding onto it, for life.

Trees turn carbon into sugar and use it to grow. In short, trees build with the carbon that would otherwise thicken the blanket of greenhouse gases overheating our planet.

And right now, Ignace’s sugar maple is pumping.

“We are in the middle of its growing season,” Ignace says, “approaching its peak activity for the year.”

Ignace says preserving trees is even more important now as they face increasing threats linked to climate change, logging and agriculture. A study out this week says 30% of tree species — some magnolias, maples and rosewoods — face extinction.

With all these threats, there’s a lot of talk about increasing efforts to plant new trees. Ignace agrees that we need more trees to fight climate change. But it would take decades to reach the cleaning, cooling and storing capacity of Ignace’s sugar maple, and it can live 300 to 400 years.

During its life, this tree may deliver direct health benefits to generations of Williamsburg residents as well. Researchers say interest in this area is exploding.

If 'We Had Pills This Good For Health'

The tiny pine sapling Robin Williams planted from a Dixie cup in 1991 now towers above her Hyde Park home.

“I raised this tree when I raised my children,” says Williams, patting a trunk that’s nearly 5 feet around. “I never thought I could grow something like that.”

For Williams, there’s something about being near this tree.

“It makes everyone a little bit happier around here,” Williams says. “When you’re looking for strength, you can’t do better than looking at a tree.”

A diverse group of scientists are studying how trees affect our bodies and minds. This growing body of research suggests many possible connections between trees and our collective or individual health.

That includes everything from better birth outcomes to fewer symptoms of ADHD, lower risk of heart disease and diabetes, less stress, anxiety and depression — even a longer life.

“Proximity to trees is associated with a ridiculously broad range of health benefits,” says Dr. Howard Frumkin, a professor emeritus at the University of Washington School of Public Health. “I wish we had pills that were this good for health.”

A few countries, notably Japan and South Korea, have invested in forest bathing, a practice that involves spending time among trees to improve health. But in the U.S., prescribing time in nature is still pretty far outside mainstream medicine.

“Proximity to trees is associated with a ridiculously broad range of health benefits. I wish we had pills that were this good for health."

Dr. Howard Frumkin

Frumkin says that may be because there are still a lot of unanswered questions: What dose is needed? What form of tree contact is best? Do you need big trees or do small trees do the trick, and do different trees deliver different benefits?

“We’re not yet able to tease the forest from the trees,” agrees Peter James, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School.

James is working on the dose question. He’s merging big data sets from phones, real-time surveys and Google Street View maps to understand what people are looking at when they report feeling specific emotions.

“We want to know what's exactly within view — is it trees, is it flowers? — and how those things are related to health behaviors and health outcomes,” James explains.

Susan Masino, a neuroscientist at Trinity College, is also researching dose, frequency and the connections people form with trees.

“Could it be beneficial to find a place that they can have as a refuge and visit often for those direct health benefits and the additional benefits of getting to know it like a friend?” Masino asks.

Researchers also are trying to figure out how long the benefits of spending time among trees or greenery lasts. One U.K. study says two hours a week is enough for people who get outdoors to report better health and a greater sense of well-being than those who don’t. The benefit was the same for people of all ages, races and income groups. And study co-author Dr. Sara Warber says it didn’t matter whether they were exercising or sitting still.

“It’s all about just getting your human self out into nature,” Warber says.

Why getting out into nature and being around trees makes us healthier and happier is less clear. But Warber says it may be as straightforward as this: “We weren’t designed to be inside houses. We were designed to be in nature, and we feel best when we’re there.”

This theory, called biophilia, was popularized by E.O. Wilson at Harvard. It suggests that time among trees helps us return to a more natural mental and physical state. It also may help to explain one link between trees and a strong immune system: When around trees we’re more likely to develop immunity to a range of germs we encounter in soil, bugs or fungi.

Another theory holds that we get more vigorous exercise when we’re in parks or forests, or that we forge stronger social bonds, which boost well-being. Researchers say there may be overlapping ways trees contribute to better health.

“We need to embrace that, even if it doesn’t fit with our scientific training of — this molecule fits into this protein like a lock and key,” Masino says.

And then there’s the theory of awe.

“It’s an emotional state where you’re presented with something that literally blows your mind, that is so extraordinary that your prior knowledge doesn’t account for it particularly well,” says Michelle Shiota, an associate professor of social psychology at Arizona State University.

Awe may help people shake off an unhealthy mood or reframe an experience. While not specific to nature or trees, Shiota took in some of those restorative moments a few weeks ago among the redwoods just north of San Francisco.

“Some of those benefits may come from looking at something that is so much larger than you and so much older than you,” she says, “and being in a space that existed long before we were here as humans and will exist long after we’re gone.”

That’s if those old redwoods survive the fires and drought that are a growing threat with climate change.

"Some of those benefits may come from looking at something that is so much larger than you ... and being in a space that existed long before we were here as humans and will exist long after we’re gone."

Michelle Shiota

Of course, there are lots of trees we pass by every day that don’t inspire awe. And some can be harmful to people who are allergic to pollen or have asthma.

There are skeptics who say we don’t need research about why nature is good for us; we can rely on common sense and take a walk in the woods. James agrees, but points to the many neighborhoods and cities where residents don’t have easy access to safe parks or even tree-lined streets.

“It isn’t something we see as an essential need,” James says. “It’s more seen as a perk or an amenity. And I really think we need to shift that thinking.”

The pandemic may help with that shift.

“It drove our numbers through the roof,” says Ned Friedman, director of Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum in Boston.

Those record crowds cemented Friedman’s view: The arboretum isn’t just a nice amenity, it’s a key piece of Boston’s health care system.

“We’re part of what keeps people out of hospitals,” Friedman says. “An arboretum like the Arnold and the other magnificent green spaces in Boston should be thought of as essential to the health and well-being of the citizenry.”

The essential health advantages of trees are not shared equally by all in Massachusetts. Access to trees depends a lot on where you can afford to live.

Unequal Access To Trees

In green, leafy neighborhoods of Newton, more than 50% of the land is shaded by trees. Parts of Arlington are at 40%. But in Chelsea, that percentage drops to just 12% of city land.

Susana Carella lives in one of Chelsea’s leafier sections, and the townhouse she rents has central air conditioning. But on this sunny afternoon, there’s no shade on Carella’s roof, and the temperature inside her third-floor office has risen to 85 degrees.

“You can start to hyperventilate up here very easily,” says Carella, “and that’s with the fan. It gets really hot.”

So Carella works most days on her first floor, where the AC works best. She's given up on outdoor exercise in the heat.

“I can’t really walk outside because I will start to get those headaches, the nausea fairly quickly,” she says.

All the unshaded pavement and brick buildings in Chelsea retain and radiate heat, baking residents even after the sun goes down. Trees provide relief — with limitations.

Madeleine Scammell, an associate professor at Boston University, runs a heat study in Chelsea that includes placing temperature sensors in trees. On the same day, in two similar trees, the temperature is seven degrees hotter in one, on the edge of a parking lot, than the other, in a Chelsea park.

“So you could be standing under a tree in a very hot pocket of the city and have a much different experience than standing under a tree in a cooler pocket of the city,” Scammell says.

The city and state are trying to close those gaps within Chelsea, and between Chelsea and more tree-filled communities, by planting and retaining a lot more trees. Chelsea is one of 18 cities where the state has created planting zones.

“We are intentionally picking those environmental justice communities, those areas of low tree cover, to try to address equity and to provide the benefits of tree cover to those most in need,” says Kurt Gaertner, assistant secretary for environmental policy in the Baker administration.

Benefits like more shade and less wind streaming through homes stealing heat in the winter; more green for better health; and more leaves to clean and cool summer’s sweltering air.

The goal is to plant 2,400 trees in Chelsea, especially oaks, elms, pagodas and hackberries that can tolerate street salt, heat and trampling. Chelsea has almost reached the goal.

Even with these new plantings, tree cover in Chelsea will only increase 5% — and that’s only if all the trees survive for at least 30 years. For the first three years of the program, 2014-2017, the survival rate is 87%. Conditions such as natural gas leaks kill a lot of new and existing trees in Chelsea.

Trees, “they’ve met their rivals in Chelsea,” says Carella.

By mid-afternoon, Carella’s back porch is in the shade of the house. The Tobin Bridge, moving thousands of cars this hour, is in full view. Jets heading to or from Logan Airport add to the noise. A few days after our interview, an air quality monitor near Carella’s home shows four times as many tiny bits of pollution and construction dust as in the Arnold Arboretum and twice as many as in Sudbury or Franklin. Pollution from trucks and cars is one reason children in Chelsea have among the highest rates of asthma in the state.

Carella creates some calm here by loading her porch with pots of petunias, zinnias and sunflowers.

“The environment has always mattered to me. I am huge into plants both inside and outside,” she says. “For me it’s my form of Zen, it’s my yoga.”

Carella knows about the clear link between spending time among plants or trees and lower rates of stress, depression and anxiety. Most Chelsea residents miss out. And some research suggests blocks with few or no trees may put Chelsea residents at greater risk for crime.

In one study, researchers compared gunshot victims to similar people who were not shot and found a lower risk of gun violence for those who spent more time near trees.

“We found that being under tree canopy cover reduced the risk of gun assault by 30%,” says Michelle Kondo, a social scientist at the U.S. Forest Service.

In addition, Kondo’s research shows that increasing tree cover in the city where she’s based, Philadelphia, could prevent up to 400 premature deaths from all causes every year.

James, at Harvard Medical School, has found a 12% lower death rate among women who live around lots of green space as compared to those who don’t. James says access to greenery is just one more way wealth buys you better health.

“We do see across Boston that the wealthier neighborhoods have more parks, more trees,” he says. “As you see neighborhood socio-economic status go up, you see green space, trees, all metrics of nature increase.”

A tree equity tool produced by the conservation group, American Forests, shows 54% tree cover in Boston neighborhoods where the median income is $190,000 a year as compared to 13% in areas of the city where that figure is $50,000.

In this light, James says increasing green space and trees in lower income neighborhoods could help reduce health disparities tied to stress. For now, the tree disparities mean it can be 10 degrees hotter in so-called heat islands like Chelsea than in wealthier suburbs with lots of trees.

Tonight is going to be stifling, and Carella expects to have a hard time sleeping.

“Last night was bad,” she says. “I think we were up between 4:30 and 5:30. I think 5:30 was when I finally passed out again.”

Poor sleep is, of course, another health hazard — one that is expected to increase with more hot nights. The cumulative effects of life with few trees just make Carella mad.

“There’s always bigger fish to fry, and so many things go under the radar that shouldn’t,” she says. “Human life is not worth any less in Chelsea than it is anywhere else.”

"There’s always bigger fish to fry, and so many things go under the radar that shouldn’t. Human life is not worth any less in Chelsea than it is anywhere else."

Susana Carella

The vital role trees play in our health and the health of our communities is getting more attention, and not just in Chelsea.

The Biden administration as well as leaders in Peru, Canada, Costa Rica and many other countries call trees and forests natural allies in the race to slow climate change.

“Nature provides us with solutions to the climate crisis,” says Interior Secretary Deb Haaland. “Achieving net zero by 2050 will not be possible without nature.”

Haaland, who spoke at an international summit earlier this summer, says we have to do much more than plant and maintain trees. In Massachusetts, where 64% of the land is covered by forests, climate experts say taking care of those areas, as well as your favorite tree, is among the critical steps the state must take to tackle climate change.

Danielle Ignace, research associate at Harvard Forest and an assistant professor of forestry at the University of British Columbia and Pam Templer, biology professor with BU’s Institute for Sustainable Energy, provided details used in scientific explanations contained in Sophie Morse's illustrations. The video atop the post was shot and edited by WBUR's Jesse Costa.

This article was originally published on September 01, 2021.

This segment aired on September 1, 2021.