Advertisement

An Excerpt From 'Rising Tide'

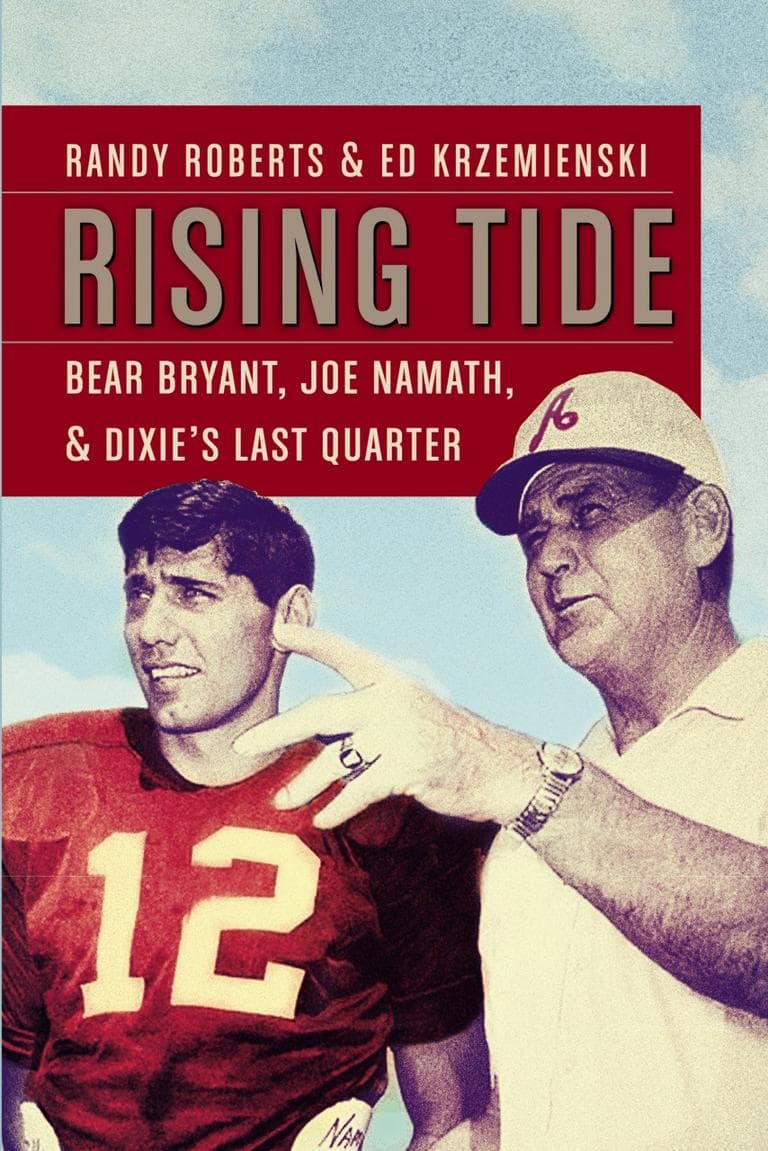

This excerpt appears in the book Rising Tide: Bear Bryant, Joe Namath & Dixie's Last Quarter by Randy Roberts and Ed Krzemienski. The authors spoke with Karen Given on Only A Game. (Read our interview and Karen's book review.)

Both teams emerged from their locker rooms at about the same time. They were greeted by a blast of fireworks, the clang of cowbells, and an explosion of Rebel yells. Before them was the Orange Bowl, done up like a football version of Disneyland. There were elaborate floats, fake orange trees with real oranges Scotch-taped to their branches, and, just past the end zones, brightly colored coral reefs with an array of beautiful girls in bathing suits lounging on them. In the stands were 72,647 spectators, some drenched and still dripping water from the shower that had hit Miami less than an hour before kickoff. Although The Jack Benny Show and The Jack Parr Show had been bumped from their Friday time slots by the game, there were enough celebrities in the audience to make up for it. Jackie Gleason, the popular television personality and “adopted pet” of Miami, strolled onto the field with a blonde on each arm to watch the coin toss. From the stands former vice president Richard M. Nixon (accompanied by Bebe Rebozo), Governor George Wallace, and Princess Takako Suganomiya of Japan watched “the Great One” go through his act. So did millions of television viewers. The Miami Herald reported that it was the largest audience to ever witness a sporting event

[. . . ] On the Texas sideline Royal realized that the best way to stop the Tide’s fabulous quarterback was to keep him on the other sideline. That meant the offense had to grind out first downs. Led by Koy, they ate up some time, and their defense was able to get a stop, but by the end of the third quarter Namath was engineering another drive. On the second play of the fourth quarter Ray kicked a 27-yard field goal to cut Texas’s lead to 21–17. Almost a quarter of play remained—and the last quarter virtually always belonged to Bear’s team.

On the Texas sideline Royal realized that the best way to stop the Tide’s fabulous quarterback was to keep him on the other sideline. That meant the offense had to grind out first downs. Led by Koy, they ate up some time, and their defense was able to get a stop, but by the end of the third quarter Namath was engineering another drive. On the second play of the fourth quarter Ray kicked a 27-yard field goal to cut Texas’s lead to 21–17. Almost a quarter of play remained—and the last quarter virtually always belonged to Bear’s team.

Throughout the game it seemed as if Texas had gotten every break. Batted balls, fumbles, and officials’ calls all seemed to go their way. But midway through the final period Alabama got a break when starting quarterback Marv Kristynik’s pass was batted into the air and landed in the hands of Alabama guard Jim Fuller. With the ball on the Longhorn 34, Namath hobbled back onto the field. After a run lost two yards, he completed two passes that moved the ball to the six-yard line. On first down, power back Steve Bowman advanced the ball to the two. On second down he was stopped for no gain, and on third moved the ball to the one.

Darrell Royal apparently had read Building a Championship Football Team and noted Defensive Axiom 3, the same one Alabama had not upheld—don’t allow your opponent to score by running from within your five-yard line. From the press box Texas’s defensive coach had called “74 Goalline,” which called for the seven down linemen to submarine under the Alabama blockers and allow Nobis and the other linebackers to make the tackle.

Namath saw what Texas was up to. “I thought I saw an opening. The time before . . . I could see the linebacker moving. I thought I could make it.” Limping, hurting, and a signature away from making more than the president of the United States, he called his own number. It called for Gaylon McCollough to work with right guard Wayne Freeman to push back the Texas left tackle, opening a sliver of space for Joe to wedge through. But just before the snap, Nobis moved into the gap between the tackles, nose to nose with McCollough. Making an instant decision, McCollough snapped the ball and drove straight into Nobis.

McCollough centered the ball, and, he wrote, “the two lines crashed into each other like 14 bulls, straining and twisting for all we were worth.” He hit Nobis and fell into the end zone. “I looked for Namath. It was easy to find him. He was lying on top of me in the end zone. We jumped up and began to celebrate.” One official indicated, “TOUCHDOWN!!”

Culpepper saw it differently. “On the snap of the ball, the Texas linemen beat the Alabama linemen to the punch and Nobis buried Namath as the Alabama quarterback tried to sneak to his left side.” Later, after watching the film of the stand, defensive coach Mike Campbell told Culpepper, “Pat, not only didn’t Namath score, not one damn Alabama jersey crossed the goal line.”

But the referees had no film to review. The line judge ran toward the play and asked, “Did he score?” “Yes,” one official said. But the head official took the ball, placed it one foot away from the goal line, and signaled Texas ball.

Alabama did not get that close to the end zone again. The game ended 21–17.

Bear Bryant never complained. When McCollough said Namath had scored, Bryant replied simply, “If [Joe] had walked in there would be no question about it.” Nor did Namath grouse. After the game a fan told him, “Good game, Joe. Good game, boy.” Namath shook his head and said, “It wasn’t good enough. It didn’t get us over.”

***

About 5,000 miles away from Miami, Sonny Namath sat at his kitchen table in the married quarters of Sullivan Barracks in Mannheim, Germany. Sipping a cup of coffee, he looked over the headlines in the Army Times. When he saw his own last name he read more closely. Something about the Alabama quarterback signing a big professional contract. That would be his little brother Joey, he thought. As he read, he made a face. “Oh, Christ, they made a mistake there.”

“What’s the matter, Sonny?” his wife, also a lifer in the Army, asked when she saw the look on his face.

He answered that “the stupid paper” never got anything right. She knew all about the Army Times’ problems. It seldom got even the most mundane facts completely correct. Even items such as the ranks of Army officers inevitably got screwed up by the paper. “What’d they do this time? Make [General] Mark Clark a private?” she asked.

“No, they got a story about Joey signing a contract with the Jets. Got one too many zeros, though. Says here he got four hundred thousand!”

“Think they’d have caught something like that.”

“Four hundred thousand. Ain’t nobody in this world worth four hundred thousand dollars! Christ almighty, this stupid paper. You ever heard anything so silly?”

Reflecting on the amount, Sonny added, “They must have meant forty thousand. Jesus, he’s really doing great. Joey got forty thousand dollars to play football! Did you ever hear anything so crazy? Forty thousand dollars to play football?!”

“Your little brother made the right decision, I guess.”

“Good for Joe.” Sonny drank his coffee and let the number sink in—the forty, not four hundred, thousand. “That’s an awful lot of money just to play a game. Unbelievable. He’s really doing great. Good for Joe. Good for Joey.”

This program aired on August 23, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.