Advertisement

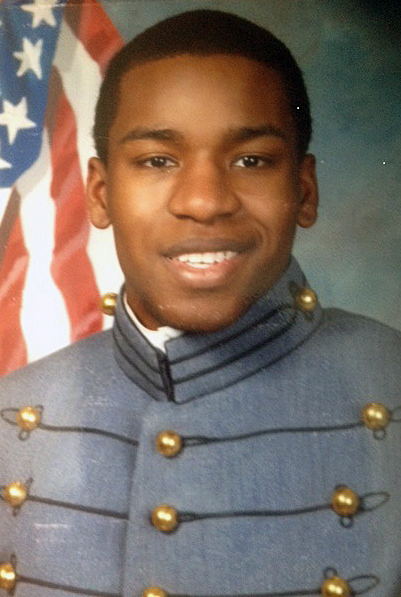

West Point's Max Lenox: Point Guard, Captain, Adopted Son

ResumeMax Lenox, a 6-foot-1 point guard, captains Army's basketball team. He has a dependable 18-foot shot, although his playing time has diminished lately.

He also has two fathers.

But I'm getting ahead of myself. S.L. Price wrote the profile of Max Lenox that appeared in the Nov. 10 edition of Sports Illustrated. He researched Max's beginnings.

"Max's birth mother was a crack smoker, an alcoholic from the age of 14, smoking cigarettes during her pregnancy," said Price. "And Max, when he was born, although he was seven-plus pounds, 21 inches, he had sort of a tenseness in his body that some people take for withdrawal. So right away, he's starting off with a lot of things going against him."

Two Fathers, One Young Athlete

That didn't deter Dave Lenox and Nathan Merrells from endeavoring to adopt Max. Having begun that process, they heard nothing for two months. Finally, Lenox got fed up enough to express irritation with the adoption agency Lutheran Family Services.

Lenox: So I called and left a message for the people saying, "OK — here's the thing: I perceive that the reason that we're not hearing from you is that you think that we might be gay, or I might be gay. Well, I am. But, we've decided there's going to be a child in our life and what I need to know now is whether you're a part of it or not. If you are, great, then let's get moving. If you're not, that's fine, but tell us, and save me a ton of money and you a ton of heartache." And that's when she called that Monday and said, "OK, you'll have a social worker immediately."

It didn't surprise me that the team members thought that he was someone that they wanted to say was their leader.

Dave Lenox

Littlefield: So she was just waiting for you to acknowledge that you were gay.

Lenox: She said, "There's no way we're going to place a child in a home with parents who are trying to hide who they are. It's hard enough to raise a kid under the best of circumstances, you certainly can't take on raising a child if you're not comfortable with who you are."

According to Lenox, Max started walking at nine months and running at nine months, two minutes. Merrells also noticed Max’s athleticism.

Merrells: One of our favorite tales involves a church we went to at the time, we put him in the nursery one morning under the care of a couple of parents. And both of them, later on, when we were sitting in the sanctuary observing the goings on of the Sunday service, one door opened on the right-hand side and Warren stuck his head in, and the other door opened on the other side and Vicky stuck her head in. And Dave and I turned to look at each other and we said, "They're looking for Max."

Littlefield: He escaped!

Merrells: Sure enough, he had gotten out of their eyesight for just a second and had proceeded to let himself out through three of those giant metal doors with the push bars. And he was retrieved by two co-eds from N.C. State. And he was a well-dressed kid and they thought, "Well, maybe he's been to church." So they bought him back into the church.

Lenox: He was three. Two or three.

Littlefield: So he was just looking for a co-ed.

Lenox: Exactly!

Merrells: He was! He was always trying to pick up chicks from day one.

'The Oldest Soul In The Room'

In his profile of Max, Price writes that Max often seemed like the “oldest soul in the room." That quality was evident on the night when his high school in Woodson, Va., celebrated the seniors on the basketball team -- an occasion Lenox and Merrells felt might be awkward.

"We'd gone to Max and said, 'Look — this is a public thing, and we get it,'" Lenox said. "'And our struggle and our battle about being gay isn't your battle. You don't have to fight that. We're fine if you want to just walk with your sister. And we're not going to feel slighted.' We would have, but we told him we wouldn't. That was a lie. And he immediately just said, 'No. This is the way it works. You're my family. And I want everyone to be there.'"

Two knee surgeries that caused Max to miss most of his junior year on the high school basketball team discouraged Maryland, Penn State, Boston University, and the rest of the schools that had been recruiting him. His senior year was his best ever, but by then colleges had already filled their rosters. So, Max opted for a post-graduate year at a military academy. There he caught the attention of the basketball coach at Army, which explains how Lenox and Merrells found themselves listening as Max and his fellow cadets were welcomed to West Point. Lenox remembered one of the high points of that welcoming address.

Lenox: "Once you leave here, you'll be an officer. And young men and women who have joined our Army, who have not had the benefit of a West Point education are going to be put under your command. And we're not letting you leave here until those young people are safe under your command." And I thought, "You idiot, he doesn't even know where his shoes are."

Merrells: Or his car keys.

Lenox: Yeah, he's constantly losing his car keys. And to watch how, within months, he's transformed into this very mature ... he still loses his car keys.

A Backup Captain

The concerns of Max's fathers were not unjustified. Max struggled academically, re-taking two classes and delaying graduation by a year. Army’s basketball team played better than it has in decades, and Max was re-elected as captain, despite averaging just six minutes a game last season. Price was drawn to Max’s story in part because it didn't always go according to script.

"Look, in a perfect Hollywood world, Max would have gone to West Point, straight A's, captained them to their first appearance in the NCAA tournament ever," Price said. "But most of us struggle. It isn't always smooth and it isn't this perfect sort of arc. Look, I give Sports Illustrated credit, because I'm writing a story about a backup point guard for a team that really has no great success at all as a basketball power."

Diminished playing time for Max was something else the whole family had to get used to.

"He and Nathan and I had kind of gotten used to — Max is always on the floor," Lenox said. "It got to the point that we weren't watching the game. We were watching Max. Is he happy? And he seemed to be. Even on the sideline, I think you see him, and you can see he's working. He's talking to every person, every person who comes off the floor, they're greeted by him. So it didn't surprise me that the team members thought that he was someone that they wanted to say was their leader."

'New Attitude'

That Max Lenox should have landed at West Point was ironic. During his high school years, when military recruiting letters arrived, Merrells intercepted them and threw them away. It's fair to say he has adjusted.

[sidebar title="Chris Herren's Second Act" width="630" align="right"]Addiction destroyed the career of highly touted NBA prospect Chris Herren. Now, Herren is making it his mission to help others.[/sidebar]"I'm going to go with this new attitude that I have, this new attitude that's been given to me by my son," said Merrells. "And I'm going to say that, yeah, it's a great thing. He has taught us so much about the military. And we have so much to be proud of and we have so much to be thankful for. And we're grateful for the service of the veterans in our country and we're grateful for the service of our own son."

West Point elected not to make Max available for this story. Though Lenox and Merrells have both said Max is glad to have his story told, they back the academy's decision.

"They're right," Merrells told me. "He's got basketball and academics to worry about. He shouldn't be doing radio interviews."

More Stories By Bill Littlefield:

This segment aired on November 15, 2014.