Advertisement

Perry Wallace's Success And Struggles As SEC's First Black Basketball Player

ResumePerry Wallace, who began playing basketball for Vanderbilt in 1967, was the first black player in the Southeast Conference. Even before he accepted a scholarship to Vanderbilt, Wallace received death threats from people who didn't want him there. But during his senior year, Wallace was voted the university’s most popular student.

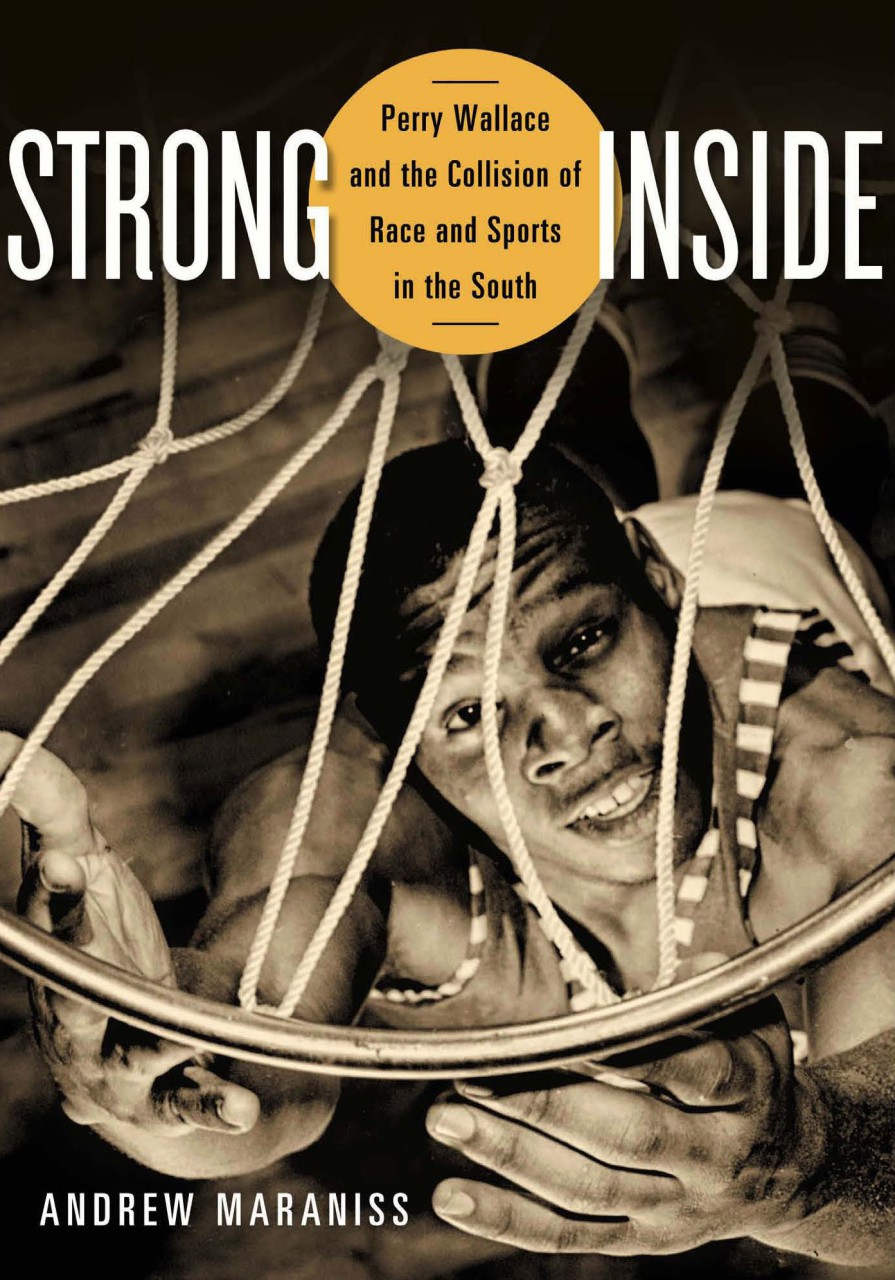

Wallace and Andrew Maraniss, the author of the new book “Strong Inside: Perry Wallace and the Collision of Race and Sports in the South," spoke with Bill Littlefield about Wallace's collegiate career and the environment in the South in the late 1960s.

Highlights from Bill's conversation with Perry Wallace and Andrew Maraniss

BL: Andrew, tell us a little about how you came to learn about Perry Wallace, and why you decided that his story would make a book.

AM: Well, I came to learn about Perry Wallace 25 years ago when I was a 19-year-old sophomore at Vanderbilt, and I read a magazine article, a student magazine article, about Perry's first game at Mississippi State, in Starkville, Miss., which you can imagine was an extremely trying experience for Perry.

AM: Well, I came to learn about Perry Wallace 25 years ago when I was a 19-year-old sophomore at Vanderbilt, and I read a magazine article, a student magazine article, about Perry's first game at Mississippi State, in Starkville, Miss., which you can imagine was an extremely trying experience for Perry.At the time, I was taking a black history course, which I didn't realize ... only existed thanks to Perry and some of his classmates who pushed for the creation of such a course in the late 1960s. It was back then in 1989 that I wrote two history papers about Perry. He stayed on my mind over the years, and it was eight years ago that I decided that I wanted to write a book.

BL: Perry, what did happen when you played Mississippi State on the road?

PW: Not only the Mississippi schools, but a number of others in the deep South, these were places where there was a great deal of antipathy and antagonism to the idea of integration. They felt it was forced on them. They felt that blacks were not equal. They made that be known at the games — with the catcalls and the screams and with the threats and with the spitting on you. And some referees, but not all of them, allowed the players to play a lot more physically against you — against me, that is to say.

Perry and Godfrey, two strong young athletes, held hands as they sat together on the bench in the locker room to gain the strength to go back out there in the second half.

Andrew Maraniss, author of 'Strong Inside'

AM: Bill, if I may, the scene that I read about in that magazine article was a freshman basketball game that Perry played in. In those days freshmen did not play on the varsity. They had freshman teams. University of Mississippi canceled its freshman games against Vanderbilt rather than play against a team that had black players. Mississippi State did not. And so Perry, and at that time there was one other black player on the team — Godfrey Dillard — played in this game in Starkville, Miss. The scene had been so outrageous in the first half — the racism directed at them — that at halftime of that game, Perry and Godfrey, two strong young athletes, held hands as they sat together on the bench in the locker room to gain the strength to go back out there in the second half.

BL: When your final basketball season at Vanderbilt was over, you felt you had something to say to the college community about your experience at Vanderbilt. Tell us a little bit about your message and how you chose to convey it.

PW: The Vanderbilt community, and the larger community, were not being given the benefit of the facts about the problems that black students were having on campus. I felt that a pioneer who comes back from exploring the West and just says, "OK, it's cool," comes back east just, "Dress casual. If you see anybody who seems not to like you, give them a hug." Well, I don't think the pioneers would have been doing their job when they came back from the West. And so what I did was I finished my job. And I did it in newspaper articles — one big one with the Nashville Tennessean.

BL: In 1970 the Philadelphia 76ers drafted you, but you ended up in law school at Columbia University and later became an attorney at the U.S. Department of Justice. Today, of course, you’re a professor of law at American University. I wonder which you enjoy talking about more -- basketball or the law?

PW: I enjoy them both. I spend so much more time with law, and some of the justice that I could contribute to, that I really enjoy, probably more, talking about that. But basketball was near and dear to my heart. I just don't breathe it and sleep basketball and that sort of thing. I kind of moved on.

Bill's Thoughts On 'Strong Inside'

Perry Wallace was a large and talented basketball player. His signature move was the slam dunk, which hardly distinguished him among his Pearl High School teammates in 1966. All of them could dunk. They liked to do it in a drill before games, because they knew the display would discourage the competition.

Vanderbilt didn't win any national championships, but the team featuring Perry Wallace braved all manner of abuse in Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia and carried on.

Bill Littlefield

When his basketball career at Vanderbilt was over, Wallace spoke publicly about the challenges he'd faced. He pointed out that Vanderbilt still had a long way to go before black students would be comfortable there. Though he'd been voted the most popular student on campus, Wallace wanted Vanderbilt's administration to understand how much more work was necessary before the university could consider itself successfully integrated.

Perry Wallace went on to become a prominent attorney. After serving in the U.S. Justice Department, he became a professor of law at American University, where he currently teaches.

In "Strong Inside," Andrew Maraniss does a fine and thorough job of telling Perry Wallace's important and compelling story.

This segment aired on December 6, 2014.