Advertisement

W.C. Heinz Revisited ... And Republished

Resume

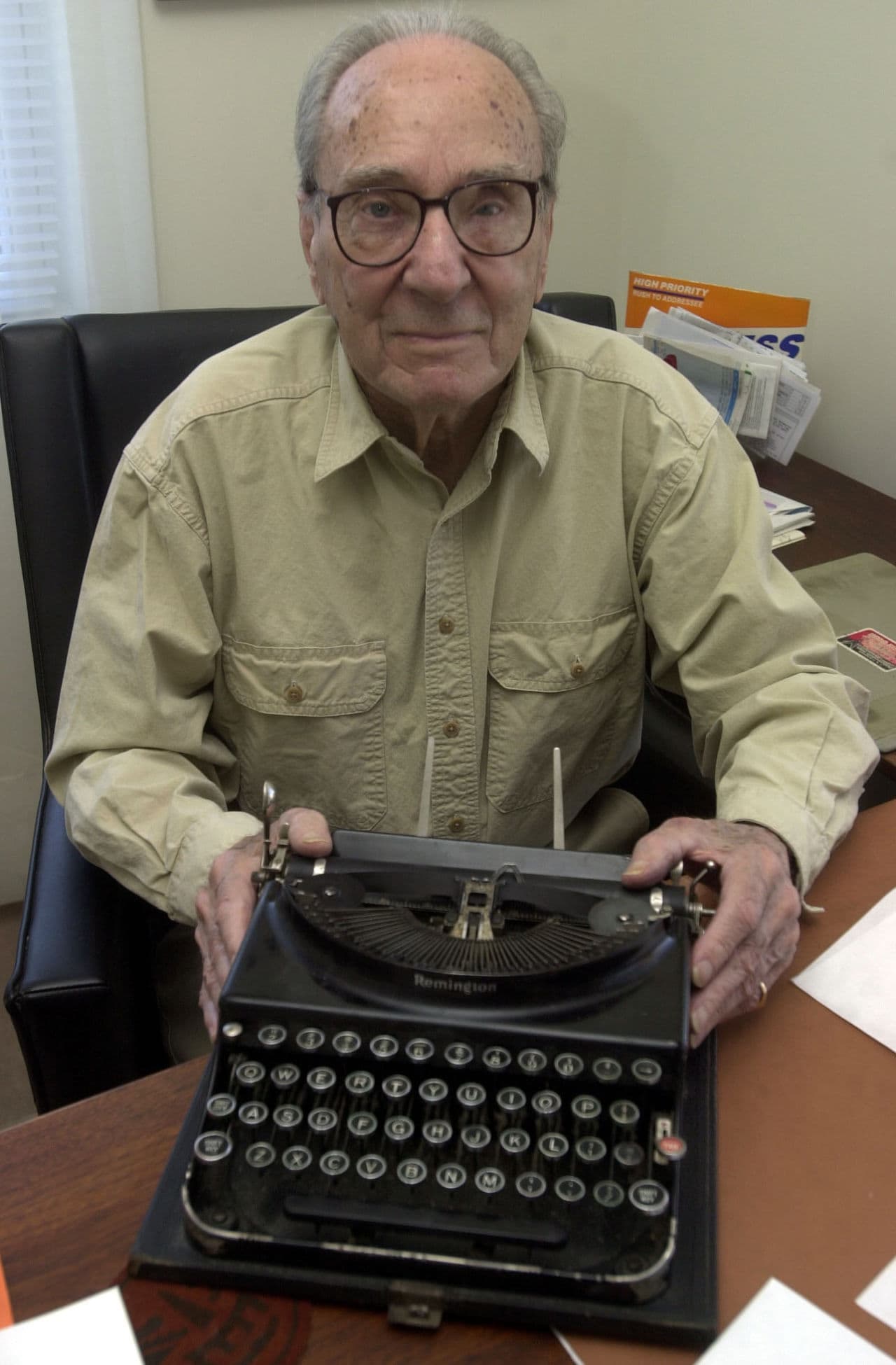

"The Top of His Game," a collection of the writing from legendary sports writer W.C. Heinz, came out this week. Only A Game host Bill Littlefield was friends with Heinz in his later years and edited the collection. Here Bill shares some of his favorite passages from the book and memories of Heinz.

I first met W.C. Heinz, who asked me to call him Bill, a little over 60 years after he was nearly flattened by a truck, the side of which featured a big picture of him.

The words beside the picture read: “W.C. Heinz. Read His Human Interest Stories On Sports Daily In The Sun. Buy It Today.” The driver of the truck was apparently in a hurry to deliver copies of the New York Sun to the places where people could buy it to read the work of W.C. Heinz, as the banner on the truck urged them to do.

In everything W.C. Heinz wrote, there is evidence that he listened carefully and saw pretty much everything there was to see.

Bill Littlefield

W.C. Heinz sold newspapers. Damon Runyon was a fan of his work. So was Ernest Hemingway. “Death of a Racehorse,” which Bill wrote on deadline on July 27, 1949, has been celebrated as the best column ever published in a sports section. It tells the story of the first and last race of Air Lift, son of Bold Venture, full brother of Assault… as promising a horse as ever stepped on to a racetrack. Air Lift leaves the gate and is running fifth, then fourth, then third. But as he seems to be about to demonstrate his class and take the lead, Air Lift breaks his leg. After a hurried call to the owner, the horse is put down. The final two paragraphs of the column provide the end of the story:

“They moved the curious back, the rain falling faster now, and they moved the colt over close to a pile of loose bricks. Gilman had the halter and Catlett had the gun, shaped like a bell with the handle at the top. This bell he placed, the crowd silent, on the colt’s forehead, just between the eyes. The colt stood still and then Catlett, with the hammer in his hand, struck the handle of the bell. There was a short, sharp sound and the colt toppled onto his left side, his eyes staring, his legs straight out, the free legs quivering.

“Aw---” someone said.

That was all they said. They worked quickly, the two vets removing the broken bones as evidence for the insurance company, the crowd silently watching. Then the heavens opened, the rain pouring down, the lightning flashing, and they rushed for the cover of the stables, leaving alone on his side near the pile of bricks, the rain running off his hide, dead an hour and a quarter after his first start, Air Lift, son of Bold Venture, full brother of Assault.”

Two years later, Heinz wrote “Brownsville Bum.” Jimmy Breslin has said this profile of an otherwise forgettable fighter called “Bummy” Davis, which Bill wrote for True, is the best sports story ever to appear in a magazine. When I spoke with him at his home in Vermont in 2000, I asked Bill to read the first paragraph, which he did:

“It’s a funny thing about people. People will hate a guy all his life for what he is, but the minute he dies for it they make him out a hero and they go around saying that maybe he wasn’t such a bad guy after all because he sure was willing to go the distance for whatever he believed or whatever he was.”

“And that was Bummy,” I said. “He was not a spectacularly admirable man, until he had the chance to do something exceptionally admirable.”

“Yes,” Bill said. “And then in the second paragraph, it says: ‘That’s the way it was with Bummy Davis. The night Bummy fought Fritzie Zivic in the Garden and Zivic started giving him the business and Bummy hit Zivic low maybe 30 times and kicked the referee, they wanted to hang him for it. The night those four guys came into Dudy’s bar and tried to do the same thing, only with rods, Bummy went nuts again. He flattened the first one and then they shot him, and when everybody read of it, and how Bummy fought guns with only his left hook and died lying in the rain in front of the place, they all said he was really something and you sure had to give him credit at that.’”

Even toward the end of his life, which came in 2008 when he was 93, Bill’s sense of humor was sharp. We first met over the phone in 1999, when I interviewed him about the anthology, "Best American Sports Writing of the Century." Later, when we spoke about a collection of writing about boxing which he’d edited, I was curious about the inclusion of one particular magazine story in the collection. It was titled “How It Feels To Be The Champ.” The byline is Rocky Marciano, and Rocky maintains that being Heavyweight Champion of the World isn’t quite what he thought it would be.

“You mention in the notes that Rocky had some help with the story,” I said. “It’s instructive, nevertheless. But did you hesitate to use it because it was ghost-written?”

“No,” Bill said. “Because I was the ghostwriter.”

He laughed. So did I.

After he’d been a correspondent overseas during World War II, W.C. Heinz returned to New York to frequent gyms, talk with trainers and boxers, and, eventually, to write a novel set in the sport titled "The Professional." Ernest Hemingway cabled from Florida to say it was the best novel about a fighter he’d ever read. W.C. Heinz was eventually inducted into the Boxing Hall of Fame.

But he wrote about horse racing, too, and baseball, and most of the other games people play, including Roller Derby. He has been credited with influencing the work of David Halberstam, among many others. He was a thoughtful reader, generous in his responses. I know this firsthand. Shortly after I first visited him in Vermont, he expressed interest in my work. I sent him a copy of the first collection of my radio and magazine pieces, published by a small press on Cape Cod. When I told Bill that the publisher had said that if I didn’t drive out to the storage unit on the Cape where he’d been keeping a hundred or so of the books, he was going to shred them, Bill was outraged.

“He can’t do that,” he said. “It’s a good book.”

In everything W.C. Heinz wrote, there is evidence that he listened carefully and saw pretty much everything there was to see. Here are the final few paragraphs of a column Heinz wrote in October of 1949, after a lopsided college football game in the Yale Bowl:

“In the parking areas an hour after the game the cars still stood, congested. On some the luggage racks were still open, and the people stood around them, the evening sun starting to darken now, the people still laughing, the glasses again in their hands.

The headlights were on by the time the last of the cars crowded out. In the West the dark clouds were starting to open, the sky to glow a little, the first star to show. The red tail-lights strung as far as you could see, the cars moving in a great company, the dead leaves swirling behind the cars, dancing in the headlights of the ones behind.

Those who had heard the rumor had heard it right. The football season had, indeed, started.”

Bill Heinz pasted his columns into a scrapbook, and under that particular column, he had written in light pencil, “good description at end.” After some of the other columns he’d written simply, “good.”

I don’t know if Bill intended for anyone to see those penciled notes, but I saw them, because about five years after Bill died, his daughter Gayl asked me to help edit a collection of her father’s best columns, profiles, and magazine pieces set in sports. Gayl and the editors at Library of America also wanted me to write the introduction for the book, which was to be titled "The Top of His Game: The Best Sportswriting of W.C. Heinz."

The book officially came out on Tuesday, but I had some advance copies, and I sent them to some friends. I sent them with pride and concern: pride that my name appeared on the cover right under “W.C. Heinz,” and concern that nothing I had written to introduce this collection of his work could be adequate to that responsibility.

W.C. Heinz was an extraordinary writer whose work is characterized by care, integrity, and the same quiet sense of humor that so delighted me almost 15 years ago, when I was fortunate enough to make his acquaintance and become his friend. It is enormously gratifying to have had a small part in what I hope will turn out to be the wider recognition of the excellence of the writing W.C. Heinz did. And it is gratifying as well to have heard recently from Bill’s daughter, Gayl, who found the introduction satisfactory, and wrote: “I know Dad would be extremely pleased … that it was you who took on the job.”

Related:

This segment aired on March 14, 2015.