Advertisement

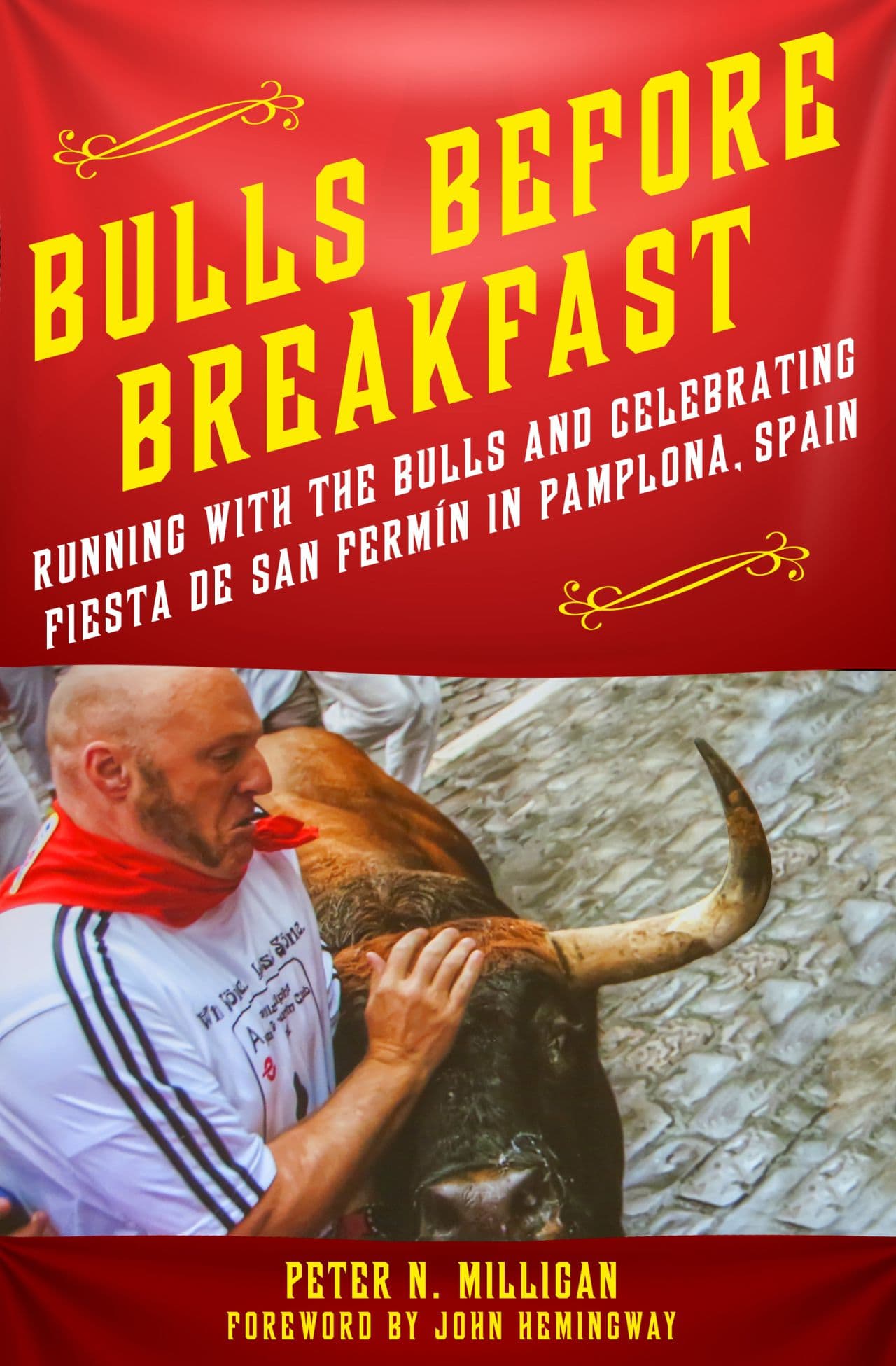

'Bulls Before Breakfast' Recaps 12 Years — And Counting — Of Running With The Bulls

Resume

In "Bulls Before Breakfast," Peter Milligan says of running with the bulls in Pamplona, “this isn’t some rite of passage to manhood. It isn’t a contest to see who can act like a jerk.”

So what is it, exactly? What motivates people to embrace the risks of running with the bulls year after year?

Milligan has been doing it for 12 years and he joined Only A Game's Bill Littlefield on the phone from Pamplona, where was doing it again.

BL: Let’s start with an explanation of how it is that you have run with the bulls as often as you have. Each trip to the fiesta in Pamplona gives you not just one, but half-a-dozen runs, right?

There’s no sign up. There’s no filing fee. There’s no permission slip. There’s no insurance waiver. If you’re over 18 and somewhat sober, you’re welcome in the street.

Peter Milligan

PM: Yes, they run every day from July 7 to July 14, as they've done now for hundreds of years.

BL: For those of us who have never run with the bulls, could you please describe what the general scene is like during the festival in Pamplona?

PM: Well, during the fiesta, it's a small city which is the capital of Navarra. It's a university town and it has a pretty active nightlife. It's a happening town, but during the fiesta it swells to about 1 million to 1.5 million people more than it normally holds. It's packed to the gills.

Every morning at 8 a.m., a couple thousand of those people run with the bulls on the cobblestone streets.

BL: I’m not sure we have time to for a complete catalogue of all the injuries you’ve suffered running with the bulls but give us the short list.

PM: Well, I've broken my ankle; a compound fracture with two bones sticking out the side; I've broken both of my elbows; I have cracked some ribs; I've been kicked in the head; the bulls have stepped on my back — they have very sharp hooves and it sliced me open. I have't yet had the privilege of tasting the horn and hopefully I will be able to avoid that for the rest of my life.

BL: Most people are bound to think that the greatest danger that runners face is being gored by a bull. But it doesn't sound like that's necessarily true?

PM: Well, there's only six bulls, but there's thousands of runners. Most people, it's their first time. There's a lot of grabbing and pushing and panic in the street when the bulls first appear. Everybody's a tough guy until the horns show up, and then a natural panic takes over. We've been pulled down — this morning when we ran, close to 25 to 30 people laid their hands on me. No ill intention, it's just a natural reaction to the fear that takes on when the bulls show up.

And they're not looking to take one person. It's not a lion or a great white looking for dinner and satisfied with one. If they have the intention of going after runners, they are not going to stop at the first one they get. They'll just go until they lose interest.

BL: Despite the obvious dangers that you've described, you maintain that running with the bulls “is not about machismo.” Help me out here, because it certainly sounds as if exactly what it's about.

PM: Well, the first time we came here, it was that. It's a celebrated Hemingway, American feeling. It's a — we're macho guys and we thought we're tough guys and we'll come over her and conquer this. But as we got to know the locals better and as we got to be more introduced to the hundreds of years tradition, we learned that you're not trying to show off. You're not trying to appear to be the toughest, the fastest, the strongest out there.

It's the bulls' last day on earth. They're running to the bull ring where later in the afternoon they will face the Spanish matadors. So you are running with them. You are not running against them. You are joining the herd. And there's a real sense of brotherhood and tradition to it. And, frankly, we find a sense of joy in throwing our head back and running as fast as we can, for at least a metaphysical second at getting as close to the bulls and joining their herd out there in the morning.

BL: Do you ever give the bulls roles in the fiesta any thought, especially considering what happens to them at the end of the day?

PM: They are the central focus. The entire fiesta here is really a religious fiesta. They are recognizing the patron saint of Pamplona which is San Fermín. And part of that is the running of the bulls, and it's been that way for not the entire life of the fiesta but for a very long time. There's a sense of reverence for the bulls. They live better than any captured animal in the world up until their death. Their death is difficult. It's bloody. It's barbaric. And anybody that doesn't want to go and see that, I completely understand.

BL: Peter, here’s one reason why I’m not sure I understand what you're up too. As you have put it, “Bulls will kill you and stomp on your lifeless body, and brag about it with friends later.” Has it not occurred to you that there may be other arenas wherein you can be, as you put it, “bold daring purposeful steady proud mighty righteous triumphant spirited?”

PM: Well, yeah. I mean, we can climb mountains. We can go hiking. We can sail ships. You know, we can go out and build cabins in the woods. There's all kinds of activities. This one's here. It's not going away, and we've found the life here. There's not a morning when we're out here when we do not take it very seriously. We have seen people maimed. We've seen people killed. There's no happiness there. There's no joy there. It's a horrible, horrible thing. We take the greatest possible care that we can and still get out there and do what we came here for.

BL: Do you have a favorite story that stands out above all the rest?

PM: My favorite story is from 2005 when we really still didn't know what we were doing. We were still pretty much cowering in fear behind the crowds and maybe hiding in a doorway or climbing up on a drain pipe to get away from the runners. And a lone bull — which the Spanish call a suelto — turned around from the running and decided to come back and investigate me and another runner who I didn't know at the time but has become a life-long friend; his name is Xavier. And he fell and the bull came after him and I jumped up on a fence.

The bull lost interest in Xavier and stood there. It felt to me like it was 10 minutes where he sat there and stared at me. Everybody says it was just a couple of seconds. And there are cowboys, the people from the ranches that help guide the bulls. They're called pastores. And the pastore cracked his willow stick against the concrete and then the bull got back to running. The photograph of me hanging from the fence with the bull ended up on a tourist magnet here in Pamplona, and I was hooked.

[sidebar title="An Excerpt From 'Bulls Before Breakfast'" width="630" align="right"]Read an excerpt from "Bulls Before Breakfast" by Peter Milligan.[/sidebar]

BL: In the final chapter of the book you ask, perhaps rhetorically, why don't most Americans understand why this is so important to us. Have you ever come up with an answer?

PM: I think that it starts with a misunderstanding of Hemingway, that it's all about being macho and showing off. Hemingway's family still comes here — two of his grandsons and one of his great-grandchildren. We've become really good friends with and we've had the opportunity to discuss this with them that there's just this sense that all Hemingway was about was grandiose macho celebrations, and I think he was probably a little bit more complicated than that. And they just don't look into it any more than it being a bucket list item.

And here it's much more than that. It's a way of life. It's not something to come and do once and check it off your list. Everybody's welcome to come and do it. It's one of the last democratic things in the world. There's no sign up. There's no filing fee. There's no permission slip. There's no insurance waiver. If you're over 18 and somewhat sober, you're welcome in the street.

Bill's Thoughts On "Bulls Before Breakfast"

He writes about the characters he’s met in Pamplona, too, and, inevitably, about the injuries he and his friends have suffered while accompanying the bulls to the fights that will, in almost all cases, end the lives of those bulls.

Beyond all that, Milligan writes with respect for the tradition he has come to cherish. He maintains that good runners “seek no praise,” and that the best and most dedicated of them are “artists.” Some of his readers will be inspired by the ritual he describes from a decidedly first-hand perspective, and they will be moved to agree with his celebration of it.

Others won’t.

This segment aired on July 11, 2015.