Advertisement

Two Inner-City Wrestlers, One ESPN Producer, One Family

Resume

This story originally aired on Sept. 10, 2016. This web feature has been updated accordingly.

Dartanyon Crockett's early life was bleak. His mother died when he was 8 years old. His father was an addict. By the time Dartanyon was a sophomore in high school, he was sleeping on friends' couches. Plus, Dartanyon is legally blind.

"Being a black kid in the inner city with physical limitations, or what people call a disability, you're already written off," Dartanyon says. "No one expects much from you. You're basically useless. And I wasn't in a position where I could fix that."

Dartanyon Crockett couldn't change his circumstances, so he did the only thing he could — he tried to hide them. Dartanyon's severely nearsighted, but he has just enough sight to get by. So he pretended he could see. He joined his high school wrestling team and didn't even tell the coaches.

"They had no idea," Dartanyon says. "I was looking at something and having trouble seeing, and it was like, ‘What's going on there?’ I'm like, ‘Oh, I'm visually impaired.’ The coaches was like, ‘You're what?’ I didn't want them to know."

Sparking A Friendship

Dartanyon didn't want the coaches to treat him any differently, so they didn't. Then one day during senior year, Leroy Sutton joined the wrestling team at Lincoln-West High School in Cleveland. Dartanyon was one of the team captains, and he wasn't the least bit worried that his team's new recruit was missing something. Well, two somethings.

"We were talking in the cafeteria, and I asked him what happened to his legs," Dartanyon says. "And he told me that, ‘Yeah, I was run over by a train.’ And I laughed, one of those deep belly laughs. He had always heard the, ‘Oh, my god. Oh, I'm so sorry. Oh, how did that happen? Oh.’ Just to see someone not feeling sorry for him, just kinda sparked a bond almost instantly."

Good thing, because when the bus showed up on a snowy day to take the team to their first wrestling match of the season, it wasn't wheelchair accessible.

"I told him, like, ‘Hey, jump on my back, we'll do this,’ " Dartanyon says.

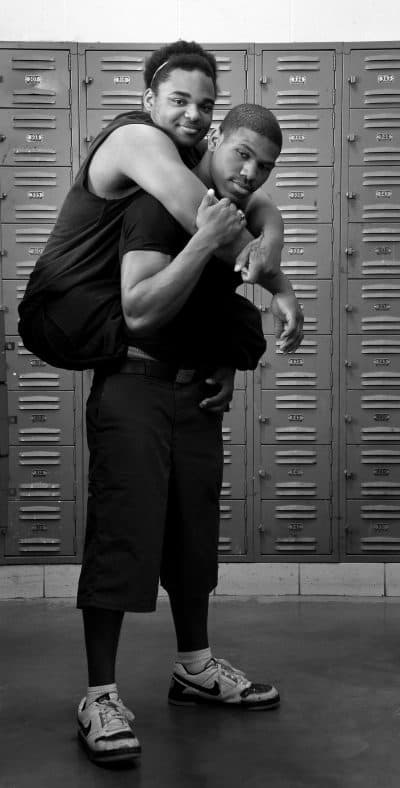

Soon, Dartanyon was carrying Leroy on and off buses, up and down stairs and into the bleachers. Leroy weighed about 170 pounds, but Dartanyon didn't think much of it. He certainly didn't think it would change his life.

"It was just helping out a friend — which, I mean, who wouldn't?" he says.

But there was something Leroy Sutton didn't know about Dartanyon Crockett.

"Nah, I didn't know he was blind," Leroy says. "I found out in class. I noticed he was, like, really close to the book we were reading. So I was like, all right, he has problems seeing. So I turned to a couple of the other students around me and I was, like, ‘Hey, man, let's do this like a project style and read out loud.’ "

And that's probably how things would have stayed — Dartanyon and Leroy helping each other out, both thinking it was no big deal — if not for an ESPN feature producer named Lisa Fenn … and her dad.

'You've Been Sent Here By God Today'

Early one morning in February of 2009, Lisa's dad called — he woke her up — and told her to check out a story in the Cleveland Plain Dealer.

"And there was a photograph of two high school wrestlers," Lisa says. "One of them was riding on the back of the other, because he had no legs. I was just completely in awe of this photograph. There was just something about the expression on Leroy's face, in particular."

“He said, ‘Did you hear me? You've been sent here by God today.’ And he said this year he'd been praying really hard for Dartanyon and for Leroy because he felt, once they graduate, the world had nothing for kids like them.”

Lisa Fenn

Lisa rushed to work to convince her boss — his name was Victor — to send her to Cleveland right away to film Leroy and Dartanyon in what was likely to be their last high school wrestling match. And all she had was this photograph.

"He said something to the effect of, ‘Are they good wrestlers?’ " Lisa says. "And I said, ‘Probably not, knowing the high school that they went to.’ ‘Are they friends?’ ‘Kinda looks like it. One's on the other's back.’ ‘Are they articulate?’ ‘Victor,' I said, ‘Just look at this picture. It's the one who can't walk being carried by the one who can't see.’ And Victor's a good man, and he just looked at me and said, ‘Have a nice trip to Cleveland.’ "

Lisa headed for the airport — she had already packed a bag. During the drive, she found a camera crew that could meet her in Cleveland and called the school. She arrived during warmups. But before she could introduce herself to Leroy and Dartanyon, she was stopped by their coach.

"He said, ‘Hey, you the ESPN lady?’ " Lisa says. "And I said, ‘Yes, I am,’ and I extended my hand to introduce myself. And he playfully slapped it away. And he leaned in and looked me in the eye and he said, ‘You have been sent here by God, you know that?’ He said, ‘Did you hear me? You've been sent here by God today.’ And he said this year he'd been praying really hard for Dartanyon and for Leroy because he felt, once they graduate, the world had nothing for kids like them."

Lisa climbed the bleachers to introduce herself to the two wrestlers. Dartanyon was excited to see ESPN — he says he felt it was about time that someone noticed him for something he was doing right. But Leroy just put in his earbuds and stared at the floor.

"I was so surprised. In 13 years, it was the first time I had ever been with an amateur or teenager who was not excited to see ESPN," Lisa says.

What Lisa didn't know yet — but would find out later — is that when Leroy was run over by a train on his way to school at the age of 11, the local paper followed him for a year and ran a six-page spread under the headline "Comeback Kid."

The paper didn't mention some of the things their reporters must have seen: that Leroy's mom wasn't taking him to his physical therapy appointments — or even making sure he made it to school. She was spending his disability checks on drugs.

"So I was like, whatever, I wasn't trying to be in the spotlight," Leroy says. "I wasn't trying to get any pity or praise for being in the chair. You know, it's my life."

Lisa knew that if she wanted to tell this story, she'd need Leroy's help. So she asked a coach — the one who had told her she was sent by God — to go with her to visit Leroy at his grandmother's house. Leroy was sitting on the floor of his basement room, playing video games. And, again, he wouldn't even look at her.

"So, for about an hour, I just made conversation with his coach, and we left," Lisa says. "I went back by myself the next night. Again, I sat beside him, on the floor this time. And, again, he wouldn't speak to me, not any more than a grunt, anyway. I asked a few questions. And so I left. I came back a third night, same thing. And on the fourth night, I said to him, ‘Leroy, I want to thank you for letting me visit you these last four days. I know it's not easy for you, so I'm not going to come back. But I think somewhere, deep inside, you have a lot to say. And I think it's probably important.’ "

"She's like, ‘If you want to tell your story or even if you just want to talk to me as a friend, then I'll be here for you,’ " Leroy says.

"My heart was really heavy as I went up the stairs because I feared … I feared that if I left, no one may ever find him again," Lisa says. "But as I got to the front door, I heard him coming up the stairs, and he called out to me and kinda gruffly said …"

"'Hey, I got this new game. You wanna see it?'" Leroy laughs. "And then, she watched me play a game "

"It felt really good," Lisa says, laughing. "Not because I had won anything, but because I know how difficult it is for trauma victims to trust. And he certainly didn't fully trust me, but he was willing to take a chance."

So, Lisa set out to tell Leroy's and Dartanyon's story for ESPN. She interviewed her subjects and researched their backgrounds. She maintained proper journalistic distance from the two teenagers. (Even though she did buy them dinner at Subway after their shoots.)

Until one day when she discovered that she couldn't be just an observer anymore.

'Go Save The Turtles'

It was at the conference powerlifting championships.

"Dartanyon was in the process of winning the whole thing when he went to the bleachers to rest, I guess," Lisa says.

"Actually, people were saying how stuff was stolen — and we went over to check, and a lot of our things were stolen," Dartanyon says.

"So, his wallet, his ID, his phone, his duffel bag — everything he had," Lisa says.

"It even had my social security card in it, because I didn't have anywhere else to put it," Dartanyon says.

"And he went into a full-on rage, where he looked capable of violence," Lisa says.

"I completely went ballistic," Dartanyon says. "Because when you grow up with nothing, and you have nothing, having something stolen from you is a huge thing."

Lisa offered to help Dartanyon replace his things. And Dartanyon accepted. But she'd need cash. So she turned to her cameraman — his name is Kameron — and asked if she could borrow some money.

"And he kinda rolled his eyes at me and let out a big sigh, and he said, ‘Go save the turtles,’ " Lisa says.

Turtles.

OK, hang with me here.

Lisa was about to do something journalists aren't supposed to do. She was going to affect the outcome of her story. And that's not a good idea — for the story, for the reporter and sometimes even for the people being interviewed.

But here's the thing: Have you ever found yourself watching a video and something really awful is happening — and no one is doing anything to stop it? For Kameron, it was watching nature films about baby sea turtles trying to survive their short walk from the sand to the sea.

"And Kameron said, ‘And then, it hits you. Sea turtles would not be endangered if the cameramen would just pick them up and throw them into the ocean,’ " Lisa says, laughing. "And he said, ‘These boys wouldn't be struggling if we helped them. So, go. Go cross that sacred line of journalistic ethics. Here's $200. Go save the turtles.’ "

The Power Of A Story

Lisa shot 120 hours of video — about 100 hours more than normal. She spent two months editing. That's a job that usually takes just two weeks.

ESPN aired the story in August 2009. Leroy and Dartanyon got on the phone as soon as it was over.

"The conversation was just, ‘Dude.’ ‘Duuude.’ ‘I know, right?’ ‘Yeah,’ " Dartanyon says.

"It was just grunts and ‘dudes,’ " Leroy says, laughing. "It was very short."

"And then we hung up," Dartanyon says. "I mean there was nothing else we needed to say, 'cause everything was said in the story. We both just understood that it was powerful."

Dartanyon and Leroy didn't yet know how much power was in their story. But Lisa was starting to find out.

"I had spent that whole edit period sort of praying that just one person would see it and want to help them," Lisa says. "And that was a very small prayer. 'Cause within minutes of the story airing, I started getting two, three emails a minute from people who saw it and wanted to help."

Soon, there was money for college, so Lisa helped Leroy and Dartanyon make it through their entrance exams and college applications. She took them shopping for school supplies. Leroy moved to Phoenix to study video game development at Collins College of Design. And Dartanyon attended school in Colorado while training with the Paralympic judo team in Colorado Springs.

Lisa thought her job was done. But it was just beginning.

"You know, I had put them on television as these resilient sort of action-figure hero friends that I saw and that I believed they still were. But now, I was dealing with essentially preteens in terms of the life skills that they had," Lisa says.

Leroy and Dartanyon struggled in school. Lisa had them both tested and found that their skills were far below grade level.

Lisa taught them how to write up a budget. But they still ran out of money almost as soon as it was deposited in their bank accounts.

To hear Leroy and Dartanyon tell it, it wasn't that bad. Leroy says the schoolwork was easy — it was just the organizational skills he was lacking. And Dartanyon admits that training with the Paralympic team was stressful. But it was nothing like the stress of wondering where he'd be sleeping the next night.

“I say this a lot, but watching this boy who had spent his life largely forgotten by this world — as his coach said, nothing for him in this life. And now he was standing at the top of a Paralympic podium with a medal around his neck.”

Lisa Fenn

But everyone agrees that the stakes were high.

"They needed to stay afloat because there was no Plan B. They had nowhere to go back to," Lisa says. "They had no family to go back to. They had no saving account to fall back on. They had no education to fall back on. It broke my heart."

The London Paralympics

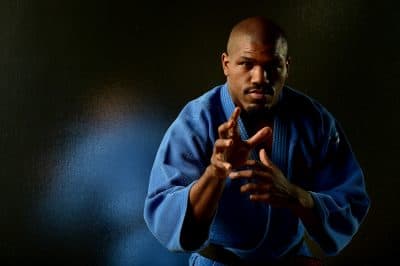

Slowly, things started to improve. Dartanyon figured out how to get to practice on time. And somehow, just two years after arriving at the Olympic training center, he qualified to compete in judo at the London Paralympics.

"I started two years too late," Dartanyon says. "Reality, I started 18 years too late, and so the idea of me making a Paralympic team just seemed sort of impossible."

Lisa and Leroy flew to London to cheer Dartanyon on. And then ...

"He did it. It was amazing," Lisa says.

"He won the bronze," I say.

"He did," Lisa responds.

"And what was that moment like?" I ask.

"Well, now you're going to make me cry," Lisa says. "It was unbelievable. And I say this a lot, but watching this boy who had spent his life largely forgotten by this world — as his coach said, nothing for him in this life — and now he was standing at the top of a Paralympic podium with a medal around his neck. It was just one of the most stirring, powerful, redemptive images I have ever witnessed."

The USOC gives American medal winners the opportunity to present a medal to the person they feel is most responsible for getting them to the podium. It's called the Order of Ikkos. And it's supposed to go to a coach.

"And I, of course, gave it to Lisa," Dartanyon says. "There was no one else to consider."

"He hung this medal around my neck and gave me a big hug and thanked me for all I had done," Lisa says. "That moment was … that was a moment of love."

"It felt really great to see how appreciative and grateful she was to receive an award or a gift, whatever you want to call it, from me," Dartanyon says.

Leroy's Letter For Mother's Day

Back home in Phoenix, Leroy was struggling. His girlfriend had given birth to his daughter, but the stresses of school and finances and being a dad were too much for him. He was diagnosed with PTSD.

Leroy saw a therapist for a while. But then he decided that he didn't want to talk to a stranger. He wanted to talk to Lisa.

"What he needed most in that moment was, again, just as I had in the basement three years prior, someone to sit beside him and wait and listen," Lisa says.

Things started to look up for Leroy. He would eventually graduate from college and get a job as a video game tester. Yes, he plays video games for a living.

But before all that, he started a tradition. In May of 2013, he wrote Lisa a letter for Mother's Day. When I asked him why he did it, it was as if he didn't understand why I'd need to ask.

"Ah … 'cause she feels like my mom," he says. " 'Cause, like, hey, she deserves this. So I did it."

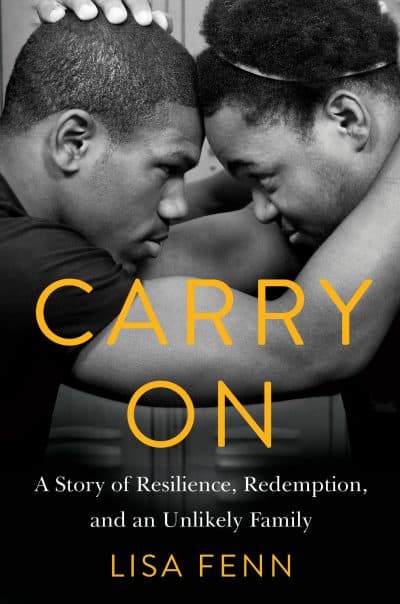

That letter is printed in Lisa's book, "Carry On, A Story of Resilience, Redemption, and an Unlikely Family." I was hoping Leroy would read it out loud for me, and he said he had a copy on his phone.

"Nope, that one's not on my phone. I have the one from this year, though," Leroy says.

"Can you read some of that to me? Is that okay?" I ask.

"Ah, sure?" he says, pausing. "Actually, it's kinda weird, but I could email it to you. Yeah, I could email it to you."

I thought Leroy was hesitating because he didn't want to share something so personal. This is the guy who made Lisa sit, staring at him while he played video games for four consecutive nights before he'd even speak to her.

So I was surprised when it showed up in my inbox just a few minutes later. It's a poem. And it goes like this:

When I first met you those were dark days,

In that time I was stuck in my dark way,

There was no light, so you set the world ablaze,

And you snapped me out of that phase,

Then you went further,

Showing me you cared,

Answering my calls now I know that you'll be there,

Then you ask questions, so slowly I shared,

This world you showed me is simply more fair,

You pull me out of a world where it was not clear,

Glad you did, there was no more air,

But now these days I'm full of smile, and full of play,

Hope you feel loved today,

So I'd like to take this moment to say,

Thank you Mom.

I love you.

"I had never gone through these things with Leroy and Dartanyon expecting a thank you or acknowledgement. It wasn't why I was in this," Lisa says. "You know, when people ask me what surprises me about our story, I say it's that they loved me back."

Since this story first aired in September of 2016, Dartanyon Crockett won a second Olympic bronze medal at the Rio Games. In the fall of 2018, he retired from the sport and is now in the final year of his sociology degree.

Leroy Sutton is still working in the gaming industry.

Lisa’s recently set up a GoFundMe account to help Leroy Sutton and Dartanyon Crockett with healthcare expenses and to “permanently break their generational cycles of poverty.”

This segment aired on September 10, 2016.