Advertisement

Aliquippa: A Town Built On Steel, Sustained Through Football

Resume

Imagine a city that used to have several reasons to consider itself pretty great.

Built for workers and prepared to provide them with all the overtime they could handle and pay them accordingly, it was a city that initially thrived, pretty much as the planners felt that it — and its inhabitants — would.

Home to folks from all over the country and a lot of the rest of the world, it was a city where everybody could cooperate productively in the mills and factories, if not always in the restaurants and bars.

And it was a city where high school football was king and provided the good players – and there were a lot of them – with the opportunity to build for themselves lives even richer than the ones their parents were living.

"There’s a real pride of place about Aliquippa, and a feeling that they’re special," says author S.L. Price. "And frankly as tough as it’s gotten, I agree with them. It’s a special place, and I’m gratified that they welcomed me there to tell their story."

It Starts With Steel

S.L. Price has spent the last several years visiting Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, the story of which begins in 1905, when the Jones and Laughlin Steel Company began establishing a company town to handle the work that had outgrown their operations 20 miles upriver in Pittsburgh.

"Essentially, they bought the remnants of a town on the ruins of an old amusement park, divided it into 12 plans: Serbs in one place, Croats in another, Irish here, Poles over there. Plan 6 was for the management-types. Plan 11 extension was for the blacks who’d come up from the south during the great migration. They said they wanted to build a town to make the best life a steelworker could possibly have."

The best life a steelworker could possibly have.

Sounds too good to be true, doesn’t it?

It was.

Jones and Laughlin built a company town in which everybody in town was dependent on the company. The work was hard and injuries were frequent. Workers were paid in company scrip, redeemable only at the company store. If they left their jobs, those workers were tossed out of their company housing by a company police force, which the company also used to discourage union organizers, sometimes by breaking their heads.

For amusement, the residents had high school football…of a sort.

"It was not a good team. It wasn’t known as a good team, really, until the post-war period," says Price.

Over the years, the fortunes of the football team rose and fell and, eventually, mostly rose. Aliquippa had baseball, too, and basketball, but the residents, no matter their race or background, tended to care most about football.

Paving The Way For A Future In Football

"I think it’s because of steel. I think it’s because of factories. Because both football and those factories depend on collective striving…on the line, on the melding of various skill sets, on the numbing repetition of the work. And if you don’t do your job, someone might get hurt. Football and steel depended on - and in some ways even in a twisted way – celebrate the trade of health for money. It’s tragic in its own, small, slow motion way."

And for a while, Aliquippa thrived…in the steel mill and on the football field. In the first three games of the 1942 season, Aliquippa High out-scored their opponents by a total of 93-6.

A little more than a decade later, a fellow entered Aliquippa High who stood just 5’7” and weighed 135 pounds. Determined to build himself into a football player, he worked out relentlessly, and, fortunately, grew a little taller. By the time he was a junior, he was big enough at 6’, 160 pounds, to be an average player on a good team and provide his family with every reason to attend games.

"His father worked on the Alleghe ny railroad, which was a railroad which ran within the mill itself. He was a burner. He worked with acetylene torches, and he was constantly coming home with burns in his clothes and on his hands, and he was a very tough guy. Little Mike Ditka, Mike’s dad."

Yeah, that Mike Ditka…one of a lot of Aliquippa boys to ride a taste for football into a scholarship to play in college and, eventually, a career in the NFL. Though according to Price, that was not young Mike’s initial plan.

"Ditka, famously and hilariously, was going to Pitt – not to be a football player, and certainly not to be a pro football player, but to be a dentist," Price explains. "And everybody in Aliquippa sort of laughs to this day at the idea of Mike, of his meat hook hands, and the joke of course is that he’d knock out your teeth and then fix ‘em for ya."

He’d have been the world’s most competitive dentist, for sure. Instead, Mike Ditka, 5’7”, 135 as a high school freshman, played well enough at Pitt to encourage the Chicago Bears to draft him. Then he won Rookie-of-the-Year honors, and set a record for touchdown receptions by a Bears rookie. Lots of people in Aliquippa noticed.

"Once Mike sort of set the example — in a high profile way — of using football as a way to get an education, it became pretty quickly clear that football was a route out. Because fathers desperately wanted their kids to not work in the steel mill and get away from the steel mill."

'A Foothold In The American Dream'

Soon, lots of people in Aliquippa stopped dreaming that their sons would become dentists…or doctors, lawyers, or businessmen. The NFL became the only goal.

Was Aliquippa unique in that respect? No. But for a time, the town was good at lots of things other than providing hard work.

"In many ways, Aliquippa was a factory, not just for making steel, but for making Americans, and the school system was very good. Many did go off, especially in the ‘50’s and ‘60’s, and use football to get their degrees. Sometimes the teams would have 10-11-12 guys going off to Division 1 schools."

So far, so good, or, anyway, better than unemployment and hanging out on the corner. Unfortunately, that would come. While Mike Ditka was coaching the Chicago Bears from 1982 until 1992, the steel industry in the U.S. was dying. Days everybody had legitimately considered long and hard began to look pretty good.

"Aliquippa was a place where a working man could raise a family, buy a house, have a vacation, maybe have a boat, and have a feeling that they had a foothold in the American dream, and that their kids could do better than they could. And once steel went down, very quickly in the ‘80’s, people were thrown out of work by the hundreds and by the thousands. This was a town built for work, and suddenly the work was taken away. In the vacuum, crime and drugs rushed in. And this is obviously not unique to Aliquippa, but it happened there in incredibly sharp and intense ways."

In 1982, Pete Eritano, a classmate of Mike Ditka’s, helped set up a food bank for the families of men who’d lost their jobs. President Reagan called Eritano to congratulate him on that achievement and tell him not to worry. The jobs would be back. The president was wrong. As Price learned, crime would increase by 40 percent the following year, and “police found themselves arresting men who’d never before been in trouble, and wives found themselves being hit for the first time.”

But football carried on. Maybe it had to. Maybe because there was nothing else to celebrate.

"With the demise of the town and the rise in crime, the reputation of Aliquippa has fallen as well. And the football team is the counter to that. It’s definitely a haven, and it serves in many ways as the fathers who aren’t there in the homes. It’s the one thing that says Aliquippa is strong and prideful and can still produce winners."

Some of the more recognizable names on the roll of winners are Ty Law, who spent 15 seasons in the NFL as a defensive back, Sean Gilbert, who played 11 seasons in the pros, and Darrelle Revis, who’s still playing today. If some of the players who got football scholarships have failed to take advantage of those opportunities and have come home to nothing much, others have followed Mike Ditka out of town. And the team has continued to win.

"They were in the state championship game last year in the western Pennsylvania, so the dynasty continues. This is a Class A school, meaning some 300 students with three dozen or less boys in the senior class. And they were playing at Class 2A for years and years, and last year they decided to move up another class, even though the population has shrunk from 26-30,000 people to 9500 or so."

A Town With 'Incredible Spirit'

But the counterweight to the success story is heavier now. Early last month, two Aliquippa High players were arrested for homicide in connection with a drug deal. Both of them were seventeen. If that story isn’t representative, it’s familiar.

"Was it depressing to have to research and tell this story?" I ask.

"Well, I mean, it's depressing in the sense that, I feel that all those forces that were cut loose in Aliquippa in the mid-80s — and other mill towns and other industries across America — are exactly what is animating much of the discontent among voters who are attracted to Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders and others. In many ways, I do think that's a depressing development because those forces are not going to go away with the end of this election," Price says.

"I will say, however, that there are, still, even with the negatives in this town, the people are incredible, their spirit is incredible. And there are enough stories of people who have gotten out. Kids are still getting out, and football is definitely being used as a way to get out, that every time I would trip over a story of negativity and I would get down about it, then I would trip over another one where someone has emerged with an incredible spirit."

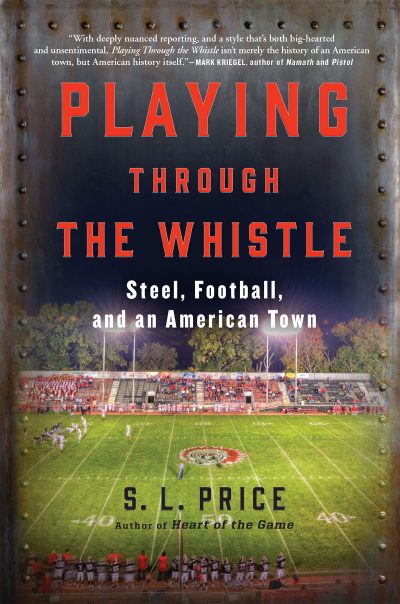

The story of Aliquippa, Pennsylvania through which is woven the story of the history and meaning of a high school football team, is much more thoroughly told in S.L. Price’s new book, Playing Through the Whistle: Steel, Football, and an American Town.

This segment aired on November 5, 2016.