Advertisement

Ryan Leaf On Drug Addiction, Recovery And Service To Others

Resume

Ryan Leaf doesn’t think that people are necessarily products of their environment.

"If that were the case, I would have never ended up in a prison cell," Leaf says. "I grew up in a really supportive environment. I had two amazing parents, two younger brothers, grandparents, a supportive community. Really loved."

Leaf’s hometown of Great Falls, Montana was like many towns throughout the U.S., at least when it came to how it treated its star athletes. By the time Ryan Leaf was 13, he

enjoyed the view from a very high pedestal.

"I was told how great I was at something, and I tended to believe it," Leaf says. "I thought I was a god. I was more important than you, because I could do this thing where I played a silly sport that made me a better human being, in my eyes."

As a junior quarterback, Leaf led his high school football team to a state title. But…

"I wasn’t a popular jock," he says. "I was the guy that showed up at the party with a six-pack of 7 Up, not a six-pack of beer. I looked at people who drank and did drugs as morally corrupt. It’s ironic, of course, to where I ended up."

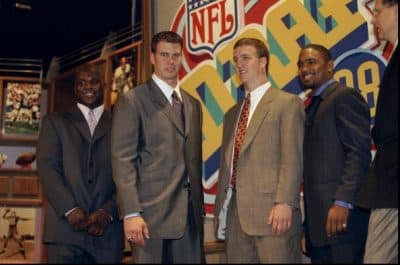

Ryan Leaf went on to star at Washington State University. In 1997, he led his team to a Pac-10 championship and a berth in the Rose Bowl. He was a Heisman Trophy finalist that year, along with eventual winner Charles Woodson, Randy Moss and fellow quarterback Peyton Manning.

"Who are going to be all Hall of Famers, I believe," Leaf says with a bit of a sigh.

From December to April, debate raged around the country concerning which young quarterback should be the top choice, Manning or Leaf.

On April 18, 1998, Leaf was sure he had it made, whatever the draft order.

"I was going to play 15, 20 years in this league, make millions and millions of dollars, win some Super Bowls and ride off into the sunset," Leaf remembers thinking. "This was a goal I had set, and I was about to achieve it."

With the first pick in the draft, the Indianapolis Colts selected a quarterback, but it was the University of Tennessee's Manning.

San Diego was next on the board. They selected Leaf.

Life In The NFL

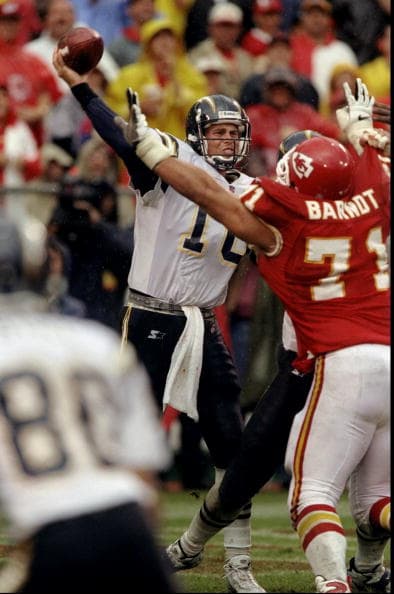

With visions of success, money and prestige dancing in his head, Leaf began the 1998 season as the Chargers’ starting quarterback. He won his first two starts.

"And then I ran into just a buzz saw in the Kansas City Chiefs in Kansas City," he recalls.

Leaf completed just one pass in 15 attempts. He threw two interceptions and fumbled three times. The Chargers lost badly.

After practice the following day, Leaf confronted San Diego sportswriter Jay Posner in the Chargers’ locker room. Posner had reported the day before that Leaf had verbally abused a Chargers’ employee.

"(Bleep)ing don’t talk to me alright? Knock it off!" Leaf had yelled.

Later that day, Leaf read a scripted apology scribbled on a piece of paper.

"I misdirected my anger after the Kansas City game," he read. "I was extremely disappointed in my performance, and I let it show."

With an obvious smirk, Leaf tossed the written apology into his locker before astonished reporters. No one had been fooled. And the damage had been compounded.

"And how I reacted after that game was what ultimately sealed my fate," Leaf says. "It was a caricature of who I was for a very, very long time."

The Chargers finished the season 5-11. Leaf became a whipping boy on sports talk radio. And he became angrier.

"I felt like everybody was wrong," he says. "I felt like I was the victim. I felt like it was everybody else’s problem, not mine. That’s how drug addicts behave. And I was a drug addict long before I ever took a drug. You’re judgmental, you’re fearful, you’re angry, narcissistic, all of those things rolled into one. And, when you’re battling the best defenses every weekend, you can’t be battling the media every single day."

In three seasons with the Chargers, Leaf would win just four games as a starter. San Diego cut him in early 2001. He learned about it in a newspaper while on honeymoon in Tahiti.

Over the next year, Leaf played for Dallas and got shots with Tampa Bay and Seattle. But new environments did nothing to improve his play or help him fathom his lack of success as a pro. Ryan Leaf retired from football in 2002. He was just 26 years old.

'That Night Would Change My Life Forever'

What Ryan Leaf wanted most was to simply fade from the public eye. And he managed to do that, until he attended a fight at the MGM Grand Hotel in Las Vegas.

"And the emcee was announcing celebrities in the audience. Charles Barkley, Tiger Woods, Dr. Dre, and the MGM Grand just cheered and applauded," Leaf recalls. "And the emcee announced my name, and the whole MGM Grand just booed and hissed.

"That had happened before, of course, just as an opposing quarterback. But you always have this armor on. The helmet, the shoulder pads. This, for whatever reason, was more about me as a person. It was just kind of sliced open and filleted for everybody to see. And that night would change my life forever because of what would happen next."

Leaf attended a post-fight party.

"An acquaintance of mine was there. He offered me some Vicodin," Leaf says. "I, of course, knew what Vicodin was from my orthopedic surgeries during my playing career. And this would be the first time that I would take them in a recreational way.

"He gave me two pills, and I mixed them with my alcohol that night, and it did its job. It was a pain killer. All the emotional pain that I was in disappeared.

"Every morning, I would wake up, and the first thing in my brain would be, 'Do I have pills?' And then once I took them, I didn’t feel anything. And I could just disappear and live in this foggy ether of nothingness."

Living In The Ether

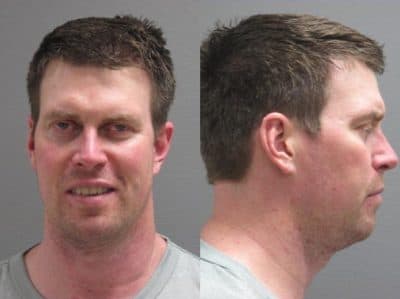

Leaf lived in that ether for most of the next eight years. During a three-year stretch, he was arrested multiple times on burglary and drug charges. The last arrest came on April 1, 2012, a day Leaf calls, “the worst of my life.”

It began when he woke up at his home in Great Falls and noticed that his painkillers had run out.

"I looked up ways to…to kill myself," he says.

He tried slashing his wrist with a knife, but couldn’t follow through with it. So he drove to his parents’ house, where he planned to asphyxiate himself in their garage. But his brother, Jeffrey, had found the towels that Ryan used to clean the blood off his arms. He called ahead. When Ryan arrived, cars blocked the entrance. So he drove past the house in search of more pills. He broke into a nearby house and stole some.

When he returned home, the cops arrived. He was tried and convicted for burglary and criminal possession. He was sentenced to seven years in prison. He served the first nine months in a lock-down treatment facility.

"I was just as miserable as I ever was in my life," he says. "You know, just because you remove a substance from somebody’s system doesn’t mean they change. Because I was doing nothing. I was as self-loathing as ever, and angry and judgmental and just fearful of everything."

Until he met a cellmate who was a veteran of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

"And he said, 'Cuz, Ryan, you’re going to get out at some point. This is what we’re going to do. We’re going to go down to the prison library. We’re gonna help prisoners who don’t know how to read learn how to read,' " Leaf recalls.

"I went begrudgingly. And I just went back the next day, and I went back the next day and, before I knew it, I realized that I was being of service to another human being for the first time in my life.

"And I knew that it was going to have to be the foundation for when I got out."

And he came to another realization.

"I was there because of what I did, and no one else," Leaf says. "And I was forced to see it in a lot of the people I was surrounded by. People who could not hold themselves accountable. I had a roommate once who simply kept telling me over and over that he wouldn’t be in there if it weren’t for the woman that called the cops on him. And I asked him why she called the cops. And he said, 'Well, I beat her up.' And I said,'Well, maybe that’s the reason why the cops were called. Because you were assaulting her.'

"They have blinders on, and I must have been exactly that same way for so long in my life – especially when I was a professional athlete. I couldn’t see what was outside me. And if anybody ever tried to place that mirror in front of me, I just removed them from my life."

Ryan's New Mission

Ryan Leaf was released in 2014, after serving 32 months in prison. He’s a new father now. He covers Pac-12 football on radio and television. In 2017, he started a foundation for people who can’t afford substance abuse and mental health

treatment. And he travels the country to tell his story.

"I was in Longview, Texas recently, and I was talking to a group of young adults who were incarcerated," Leaf says. "And when I made the statement to them that they were just as important as Dak Prescott, there was a shocked look on many of their faces."

Prescott is the highly successful quarterback for the Dallas Cowboys.

"They don’t see themselves as another human being at the same level as somebody like him."

Ryan Leaf’s mission these days is to convince people that they are as important as celebrity athletes. He’s qualified for the job. And doing it has led him to a new perspective.

"I defy anybody to be of service to another human being and not have the most peaceful night of sleep you’ve had in a long, long time," he says. "Those ideals that I thought were important, or what I thought success was, have been replaced completely.

"If I do the next right thing on a daily basis, not just good things happen for me, but great things."

And if he doesn’t do the right thing?

"I end up in a prison cell," Leaf says.

Ryan Leaf is currently the Program Ambassador for Transcend Recovery Community.

This segment aired on April 28, 2018.