Advertisement

Golf Artist Valentino Dixon Draws Himself Out Of Prison

Resume

Valentino Dixon is an artist.

"I learned to draw when I was about 3 years old," he says.

His early drawings were mostly of cartoon characters and Disney figures. But they weren’t an escape from the tough East Buffalo neighborhood where he lived.

"Well, not at the time," he says. "It became an escape for me later on in life."

Dixon attended a school for the arts when he was a teen. But he started hanging out with drug dealers. When he was a bit older, he dealt cocaine to support his baby daughter. He often carried a gun. He was out on bail for possession charges on the night of Aug. 10, 1991.

“It could happen to you or a loved one. It could happen to a family member. This is why it’s so serious.”

Valentino Dixon

"I was hanging out at a fast-food restaurant," Dixon says.

Journalist Max Adler says there were about 70 teenagers at the restaurant that night.

"It was a popular night hangout spot, and there was a melee," Adler says. "There was a fistfight that turned into a gun fight."

"Shots rang out," Dixon says. "And I took off, jumped in my car, pulled away."

"He fled," Adler says. "Didn’t want to have anything to do with this. There were four people shot, one of whom, Torriano Jackson, was 17 years old. He died."

The Investigation

"Shortly thereafter, I was pulled over, taken in for questioning," Dixon says.

The police interrogated him.

"They asked me, 'Was I at the scene of the crime?' Which, I told them, 'Yes.' Next thing you know, I’m being charged with murder," he says.

Dixon couldn’t believe what he was hearing. But he felt eyewitness accounts would clear him.

"There were dozens of witnesses — all of whom gave conflicting accounts of what happened," Adler says.

According to Adler, seven eyewitnesses insisted that Dixon had not committed the crime. And, just two days after the shooting, a man named Lamarr Scott confessed to the murder. And, yet, the prosecution of Valentino Dixon proceeded.

"Nobody wanted to admit that a mistake was made," Dixon says. "It came down to embarrassment. It came down to egos. The culture was that, ‘We're not going to say that we made a mistake here.’

"Anybody that knows me knows that I was never capable of what they accused me of. And that’s what hurt me to the core. You know, why would you accuse me of this? And then, when you realized that I didn’t do it, why would you ignore that you made a mistake?

"I mean, that’s, like, the worst thing in the world that you can blame a person for. Is murder. Like, come on, it don’t get no worse than that."

The Trial

The case went to trial in 1992. Dixon hoped the discovery process would clear his name. But …

"Next thing you know, the prosecutor’s charging two of the witnesses with perjury before trial," he says. "For stating that I did not commit the crime, he charged them with perjury."

"And then this made other witnesses afraid of coming forward," Adler says. "Instead of just kind of letting the jury have all the facts and letting them sort it out, the prosecutor very vindictively selected who could testify. And that was only the people who agreed with his version of the story."

A good attorney would have been able to protect his client. But Dixon’s public defender, who had only visited him once in the 10 months leading up to the trial, was anything but that.

"Trial begun — the lawyer didn’t even give an opening argument," Dixon says. "He waived his opening argument. And then he didn’t call any witnesses. Not one witness to the stand. He didn’t even introduce one exhibit during trial.

"The jury found me guilty," he says. "Gave me 38 years."

Thirty-eight and a half years to life, to be precise.

The Incarceration

In 1992, at the age of 21, Valentino Dixon went to Attica, the infamous maximum-security prison in western New York state.

"For the first seven years, I was such in a state of depression," Dixon says. "I didn’t have no drive or no determination when it came to anything positive."

Valentino learned what he could about the law at the prison library. He kept a meticulous list of the mistakes that had been made in his trial. He filed an appeal.

"The same judge, when we filed a post-conviction motion, said I received a fair trial," Dixon says.

Adler says Valentino’s family was still fighting for him.

"His father did all he could to take the investigation into his own hands," Adler says. "And attorneys would take his money and then not really do anything. It became his nightmare."

Dixon was despondent.

Rediscovering A Talent

But then he received a package from an uncle.

"He sent me some colored pencils and some paper," Dixon says. "I kinda tossed them into the corner of the cell. And he kept saying, ‘Hey, when are you gonna use the pencils?’ And finally I just came around and said, ‘All right, let me see what I can do.’ And I started drawing.

"I was drawing everything. From African art, abstract art, landscapes, animals, you name it. Once I picked up the pencils, I wouldn’t stop."

“A tranquil image of grass and skies and tree, water. ... It was just as far away from his cell as you could possibly get.”

Max Adler

Dixon drew every day. In 2010, his drawings got the attention of the warden.

"One day he says, ‘Dixon, you think you could draw my favorite golf course?’ And I say, ‘Yeah, yeah, I’ll draw it for you. It’s no more than a landscape and a flag, so why not?’ "

The warden brought in a photo.

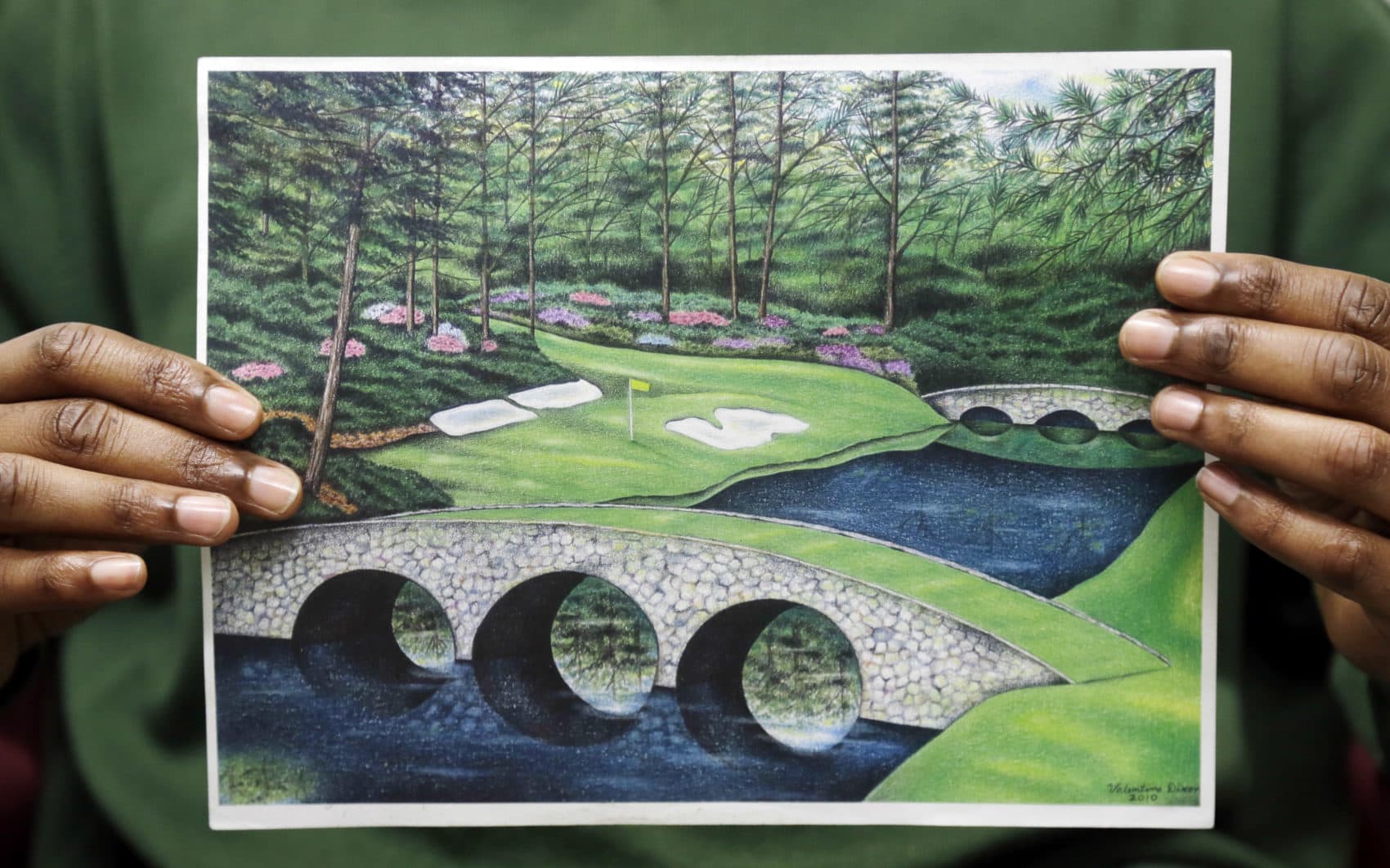

"It was Augusta," Dixon says. "I believe it was the 12th hole. I drew it for him. He loved it."

A cellmate told him he should draw some more golf courses.

"I said, ‘What am I gonna draw golf courses for? What are you talking about?’ " Dixon remembers. "So he says, ‘I think you could do good drawing golf courses.’ For whatever reason, he planted a seed. And I started drawing golf courses. It was the strangest thing in the world."

Strange, because Valentino Dixon had never even set foot on a golf course. So he collected golf magazines and drew the pictures he saw in them. But he didn’t just look at the photos.

The Letter

"I started reading the columns," Dixon says. "And I came across Max’s column 'Golf Saved My Life.' "

That was the name of a monthly Golf Digest column Max Adler co-authored.

"We chronicle the ways people used the game to get through a hard thing that they were going through in their life," Adler says.

"I had friends that committed suicide in prison," Dixon says. "You can be strong today, and tomorrow you can be, like, 'You know what? I got 20 years, and I’m ending this. I can’t do no more time.' And I felt like, at that point, I was on borrowed time — and golf was saving my life."

Then, one day in December 2011, Max Adler went to his office at Golf Digest.

"And in my inbox was a little letter postmarked from Attica Correctional Facility," Adler says. "And inside was an amazing letter from Valentino."

In the letter, Dixon explained what had happened to him. He said he was innocent.

And there was something else in the envelope. A tiny drawing.

"It was a golf green surrounded by trees in autumn foliage," Adler says. "And it was just painstakingly rendered, in layers upon layers of colored pencil, to achieve a very vivid, rich color that’s almost like painting. A tranquil image of grass and skies and tree, water. ... It was just as far away from his cell as you could possibly get."

The Meeting

Adler visited Dixon in early 2012. At first, he thought the story was about Dixon’s art, not about his innocence.

"I entered Attica that day with some serious doubts — some questions about the story that he had told me," Adler says. "And, sitting in the same room with him, he really spilled his heart out to me. Told me everything he could about his life and his case over the course of a few hours. And I left there convinced that a real injustice had been done, and that I was gonna try to do everything I could to tell the story."

Adler pored over thousands of legal documents. In July of 2012, the story appeared in Golf Digest.

"It was a first-person piece written by Valentino Dixon — ghost-written by me — which really just explained the peace and tranquility that he found in the look of this sport," Adler says. "And then, attached to that, was a much longer piece that investigated his case and showed that it was a pretty clear instance of local officials seizing the moment to railroad a young guy with a criminal background into prison for a crime he didn’t commit," he says.

Major news outlets became interested. And that wasn’t all.

"Golf Digest is really what led us to discover it," says Georgetown Government and Law Professor Marc Howard. He’s the Director of Georgetown’s Prisons and Justice Initiative. In January of 2018, Howard presented Dixon’s case at Georgetown in a class called 'Making An Exoneree'. Three undergrad students went to work.

"And they actually visited him in prison," Howard says. "And they made a trip to Buffalo, also, where they went to the crime scene, where they interviewed the original prosecutor, interviewed a number of witnesses and met his whole family, interviewed the current DA. So they did an incredibly thorough job and became more and more convinced that Valentino was 100-percent innocent.'

The current district attorney, Erie County Prosecutor John Flynn, promised he would thoroughly review the case.

An Exoneree Is Made

On Sep. 19, 2018 Valentino Dixon got his first real day in court. That day, he walked into court wearing shackles. He walked out a free man.

On the day of his release, there was a party. Marc Howard, Max Adler and many of Dixon’s family members and friends joined him at the restaurant he’d seen in ads for decades on prison televisions.

"We went to Red Lobster," Dixon says. "I had never ate lobster before. So while I was in prison, that was like a dream — like a fantasy to me — for me to eat lobster."

Dixon says he’s not bitter about the 27 years he spent in prison. But he says that, if his drawing had not captured the attention of Max Adler, he’d still be sitting in jail.

"I’m glad it worked," he says. "Because, I’ll be honest with you — at one point, I felt like the only way I could get out is through my artwork. So I says, ‘Maybe I can draw myself out of jail.’ And who could have predicted that?"

He also says those who wrongfully convicted him should be embarrassed.

"Well, yes. Extremely embarrassed," Dixon says. "Because the law states that a prosecutor has a duty and an obligation to seek the truth, not just a conviction."

Marc Howard estimates that, among this country’s 2.3 million people in prison, 3 to 5 percent have been wrongfully convicted. That’s about 100,000 people. Dixon says every American, not just African-American kids from tough Buffalo neighborhoods, should find that disturbing.

"Yeah, because it could happen to you or a loved one," Dixon says. "It could happen to a family member. This is why it’s so serious."

Making Up For Lost Time

Since his release, Dixon has advocated for criminal justice reform. But he’s also caught up on some fun. The first thing he did, he said, was to make breakfast for his mother and grandmother. In late 2018, he traveled to Mexico with Max Adler to play golf for the very first time. Before that trip, he told me...

"I don’t care how I do," Dixon says. "It’s gonna be a wonderful moment. And I’m gonna enjoy myself. What is a good score? Um … 68? If I did 10 times worse than that, I’m still gonna be happy just to be there. My score is 680, and I’ll still be happy."

You can read more about Valentino Dixon and purchase prints of his artwork here.

This segment aired on November 10, 2018.