Advertisement

The Story Of The First Climbers To Scale Yosemite's El Capitan

Resume

Eighty-seven-year-old George Whitmore lives in Fresno, California.

"Born here, still here," he says.

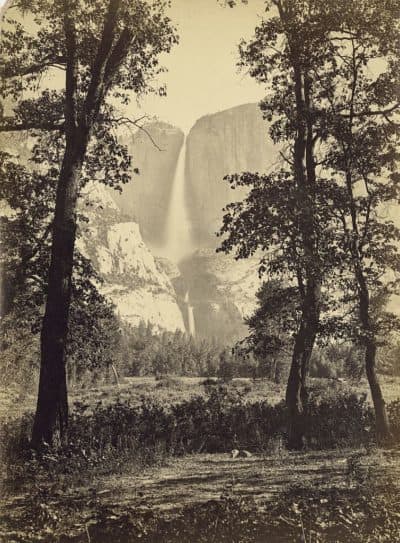

When George was 5 or 6 years old, his parents took him to the bridge across Lower Yosemite Falls. They looked up at a two-tiered cascade of water thundering over a cliff, kicking up a canopy of mist over those standing below.

"I was pretty small," Whitmore says. "And I was surrounded by all these big people who were looking up. And I wondered: What are they looking at? They were looking up on the cliffs — way up high. And I was told, ‘They're looking at the climbers up there.’ I was very frustrated, because I could not see any climbers. And that was my first exposure to rock climbing."

Two decades later, George Whitmore would join one of the most accomplished climbers of his era to take on one of Yosemite’s most iconic features.

The Early Days Of Climbing

In the early 1950s, there were very few people rock climbing. The activity tended to attract rebels — people who marched to a different drummer.

Two of those people happened to be George Whitmore's housemates in San Francisco.

"They said, ‘Well, why don't you come out to one of our practice climbs? We're having one this Sunday,’ " George remembers. "And then, if you went to enough practice climbs and learned enough, then you would be allowed to go up to Yosemite with them."

Meanwhile, in the tiny rock climbing community, a bit of rivalry started between two fierce competitors: Warren Harding and Royal Robbins.

"Robbins was an athlete — like, the first real rock athlete in the United States — at least operating in Yosemite on that level," says author John Long, who has written about the history of climbing. He says Royal Robbins was a free climber — he wanted to make his way up the rock with as little equipment as possible.

"Harding didn’t care about free climbing," Long says. "He didn’t care about putting bolts in the wall. He didn’t really care about anything but getting up things. You know, each wanted to outdo the other one.

"And so it went. And that’s what drove a lot of the technology and the technique and the development of the sport — is those two guys going about their business in different ways."

The battleground was Yosemite National Park, with its valley surrounded by a cathedral of steep, granite cliff faces.

Warren had wanted to be the first to climb the face of Half Dome, the sliced rock made famous by Ansel Adams’ photography. But in July of 1957, Royal Robbins' team got there first. Warren is said to have met them at the top to congratulate them, but …

"Two days later, he says, ‘I’m going after El Cap,’ " Long says. "So he lost Half Dome, but he was gonna go for the bigger one. Which is El Cap."

'El Cap'

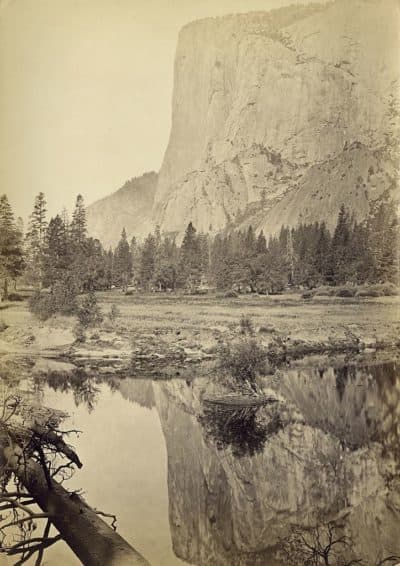

“El Cap” — as in El Capitan. The two sides of a cliff come together in a nose shape stretching down the bottom. That’s the route Warren and his crew planned to take: “The Nose.”

Warren Harding died in 2002, but he described the climb in a report he wrote for American Alpine Club in 1959.

We spent an entire day studying the face in search of a continuous route to the summit. It was obvious that existing methods of conducting a sustained rock-climb would be inadequate. Because of the extreme difficulty of the climbing we anticipated slow progress — perhaps no more than 100 to 200 feet a day.

Long says El Capitan was considered the greatest prize in rock climbing. It’s steep, it’s long and large cracks in the granite block the path. At times, you’d have to hang upside down to work your way up.

"It’s just scary as hell up there, man," Long says. "You’re with — you’re talking about way up, thousands of feet off the ground — with just the, the gnarliest, least effective gear your could ever imagine. I mean, really, just winging it up there."

Warren and a couple others began their first attempt on July 4, 1957.

There was no thought of reaching the summit ... our tentative goal was El Cap Towers, the prominent pinnacles on the east side of the buttress about half way up the face. ... The climbing was almost entirely 6th class, direct aid, and about as difficult as can be imagined.

That first attempt only lasted three days.

Our special "stoveleg" pitons which had brought us up 300 feet of the two- to three-inch-wide "Stoveleg Crack" ... would no longer hold.

A piton is a type of anchor — a piece of metal that a rock climber drives into a crack that’s too narrow for an arm or a leg.

"They didn’t have anything that would fit the crack, and nobody could free climb it because it’s vertical two inch, two to three inch," Long says. "There’s no way for ‘em to make any progress. They had to retreat and try to fashion something that they could beat into the crack."

One hundred and fifty feet short of the lower tower, we were forced to give up. ... Leaving fixed ropes behind to secure what we had gained, we descended. Reaching the ground, our spirits were somewhat dampened by an unexpected problem. It seemed that our climb presented quite a spectacle and had attracted a crowd of tourists which created a traffic jam at the road-junction near the base.

"And it was such a freaky, sort of other-worldly kind of thing," Long says. "Even back in those days, Yosemite was fairly crowded with car travel — and half of it was parked in El Cap Meadow. Everybody wanting to get a peek of these maniacs up on El Cap trying to climb the thing."

Because of the crowds, park rangers banned climbing between Memorial Day and Labor Day. So the team had to pack it in for the year. In spring of 1958, Harding tried again with a new team. One of the members was Richard Calderwood.

A New Team

"I thought it was quite an adventure," Calderwood says.

Calderwood’s main job was mostly to ferry supplies and clean up the rope behind them.

"I did a lot of cargo carrying and load ferrying — kind of a porter or a ‘sherpa’ as it were," Calderwood says. "I was working all by myself. That was kind of trippy. You know, up there, a couple of thousand feet off the ground, just having to really be sure that I was doing everything right and that I wasn't making any mistakes. Because a mistake could be fatal."

George Whitmore was also on the climb. He’d come a long way since his San Francisco housemates had taken him on Yosemite practice climbs. Whitmore also hauled supplies, including extra bolts.

"At that time, they didn't have these portable ledges like they have now," Whitmore says. "You either spent the night hanging in rope slings or you found a ledge that you could lie down on or sit on. You sort of sat there with your legs dangling over the edge. And that was how you spent the night: just sort of sitting and leaning back."

This time around, they were doing what Warren called a series of “attrition attacks,” weekend climbing adventures meant to set ropes high enough on the rock face so that a final push would have a chance of success.

"If anything had happened to us, it was up to us to take care of it ourselves," Whitmore says. "Nobody was going to come after us. Nobody was going to rescue us. The type of climbing you're doing is beyond what anybody has had any experience with. You guys are on your own."

“Let's go up there and stay with it until we finish it or it finishes us.”

Warren Harding to George Whitmore

As the climb continued, it became clear that the team would need to develop new climbing methods if they were to reach the top.

"I had prusiked before, which is the process of sliding knots up the rope and standing on stirrups and so forth in a harness and working your way up the fixed rope," Calderwood says. "But I'd never done it on a rope that was anchored, say, 150 feet above. There's a lot of stretch in the rope. And I remember pushing the knots up and putting my weight on it. And I didn't go off the ground. I did it again. I was still on the ground. It took quite a while before all the stretch came out."

At that point, climbers hung from the waist, which made it hard to lug gear quickly. So Calderwood started thinking of ways to improve their equipment and technique. He designed and built a chest harness, which he sewed out of salvaged seat belts.

"And we made faster progress," Calderwood says.

But still, for George Whitmore and the rest of the crew, it wasn’t fast enough.

"We would take so long," Whitmore says. "You know, we would be at work or in school up until Friday. Then we'd go up there Friday night. Saturday morning, start up the ropes. Get up to the high point, push the high point a little bit and then have to start back down and go back to school and work.

"And it was getting to the point of diminishing returns. It was ... we were expending huge amounts of time and effort and making very small, incremental progress."

One Sunday evening, Warren came down from the weekend climb, again not getting very far. He was frustrated.

"And as he was dropping this gear that was wrapped all around him, he said, ‘I'm getting sick, sick, sick of going up and down these goddamn ropes. Let's go up there and stay with it until we finish it or it finishes us,’ " Whitmore remembers.

The Final Climb

On November 1, 1958 we started up the fixed ropes for what we hoped would be the last time.

Winter was coming. It was now or never. But before the team reached the top, Richard Calderwood decided the answer was “never.”

"I was married and had a baby on the way," Calderwood says. "And I was off on this adventure. And the adventure was very exciting and I was enjoying it, but it seemed selfish in terms of the responsibilities I had — to go playing around, seeking adventure when I, perhaps, ought to be supporting a family."

“I do recall that El Cap seemed to be in much better condition than I was.”

Warren Harding

Calderwood says he developed a lot of anxiety over what to do. He didn’t want to stay. He didn’t want to quit. And most of the time, he was alone on the rock face with a lot of time to think.

"So, yeah, I'd have a lonesome night to think and reflect and look at the cars going around down in the valley and so forth," Calderwood says.

So Calderwood went home. And Harding, Whitmore and Merry pushed on. Whitmore remembers one night when they were getting close to the top. It stormed — remember? Winter's coming? — and he got wet.

"So in the morning I was drying my stuff out — so I got a late start going up the ropes," he says. "And when I got up to Camp 6, which is where I expected to find them, there was a note tied to the rope: ‘George, we're going for the top. Come on up.’ OK. It was dusk. OK. Keep on going."

Whitmore knew the lead climbing team would soon run out of bolts, so he brought some along. As he climbed higher, he found them waiting for him.

"So, here was Warren up in under those overhangs," Whitmore laughs. "And it was ... it was pretty dark by then. But you could see this little dark spot up there under the overhangs. That was Warren. ‘Did you bring some bolts?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Boy, are we glad to see you!’ And then Warren spent the night driving these bolts over the final overhangs. Topped out as the sun was coming up."

As I hammered in the last bolt and staggered over the rim, it was not ... clear to me who was conqueror and who was conquered: I do recall that El Cap seemed to be in much better condition than I was.

"When all three of us got on top and our two friends were there, yes, they had a bottle of champagne and they had three champagne glasses. Real glasses, not plastic," Whitmore says.

That climb up El Capitan didn’t only bring innovation in gear, but author John Long says it also brought a new way of thinking about big-wall climbing.

"It’s really like walking on the moon," Long says. "It’s one of those things that happened — like Greg Noll surfing Waimea Bay the first time. You know, there’s certain things that happen that ... that are seminal events. Not just for climbers or surfers or astronauts, but for all mankind. And that was one of ‘em. It revolutionized what everybody thought was possible."

Warren Harding and his crew reached the top of El Capitan 60 years ago this month. It took them 45 days over 18 months. Today, it takes just a few days to climb that same route. At night, you can see their tiny beams of light from the Yosemite Valley, beckoning new climbers to take on the adventure.

This segment aired on November 17, 2018.