Advertisement

Public Pensions, Under The Gun

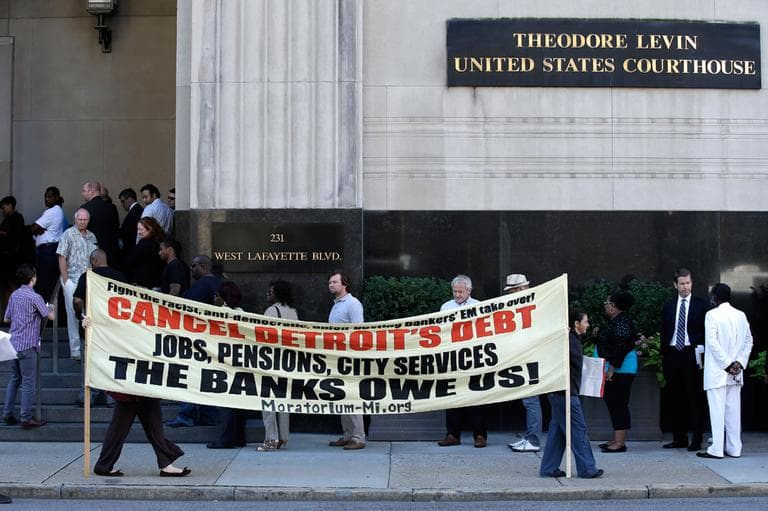

ResumeBankrupt Detroit has cutting pensions on the table. Plans across the country are underfunded by a trillion-plus. We ask what's coming.

Detroit is in crisis, and the city’s emergency administrator says Detroit’s public pensions have to be on the table as the city faces bankruptcy. On the table as in "on the chopping block." We’ll see what happens.

The average public pension in Detroit is $19,000. For pensioners, there’s not a lot to cut.

But across the country, coast to coast, many cities, states and towns are looking at pension numbers that do not add up. And a political environment that may say "bring in the axe."

This hour, On Point: Solemn promises and red ink. Public pensions, under the gun.

-- Tom Ashbrook

Guests

Kil Huh, director of state and local fiscal health at The Pew Charitable Trusts. Former director of policy and consulting at the Fannie Mae Foundation and previous manager of the foundation’s state and local initiatives. (@KilHuh)

Monique Morrissey, economist at the Economic Policy Institute, focusing on retirement security.

Robert Pozen, senior lecturer at Harvard Business School and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. (@Pozen)

John Day, retired police detective for the Detroit Police Department.

Interview Highlights

Kil Huh explains how Detroit got to the point of bankruptcy:

Detroit has, in the past, borrowed to cover its pension obligations. In 2005, it issued what's called a pension obligation bond, essentially money that they borrowed to put back into the financial markets to cover their bills but then to also earn some return so they could be in a better funding position going forward. Part of what Detroit needed to do is put aside their annual contribution that their actuaries recommend, and that's something Detroit has consistently failed to do. So the combination of borrowing to pay for promises that already been made and benefits that have already been earned, along with a persistent underfunding year after year is really what drove Detroit to where it is now.

Cutting back on pension benefits, a promise they've already earned, as well as not fully paying back their investors are just two choices that Kevin Orr as well as the bankruptcy judge will have to make. They also have to worry about putting police officers on the streets, picking up trash, cleaning streets, as well as turning on the lights, which is a real problem for Detroit.

Monique Morrissey on the two unique qualities of Detroit's banrkuptcy:

What's happening that's brand new is this attempt by some places to try to actually get at the pensions of people who are already retired, which is really rather shocking. Somebody's that already collecting a pension, who's already done the work, and — I would like to emphasize — who accepted lower pay, much lower pay and often made significant contributions to this pension out of pocket. So typically public sector employees pay a good share of their pensions out of pocket, and they also typically are paid less than equivalently educated people in the private sector. So they've already done the work, they took lower pay, they contributed to these pensions, and then we're saying, "Oh, well, sorry. We're just going to take some of this back." That and the fact that it's a large city declaring bankruptcy — those are the two things that make Detroit big news.

Robert Pozen on how to prevent a situation like Detroit's:

When you get to a point like Detroit, there are no good choices. The key is to start working on this in advance. We have lots of pension funds that could go either way in states and cities, so they need to get their expected returns down a little, they need to meet their contribution requirements, they need to look at their cost of living — they need to do all these things and get it into order. Unfortunately, once you get to the point where Detroit is, there are no good choices left.

Pozen on retiree health care costs:

Retiree health care obligations are actually larger than public pension funds. If we look at the Pew statistics, they say that for the 50 largest cities, it's about $25 billion larger, retiree health care. And retiree health care does not require any funding; there's no advance funding in almost any city or state government. So that's another thing we need to change. We need to get everyone on Medicare or Obamacare or alternatively we need to start funding it. We haven't funded that at all. The average funding is 0 to 5 percent.

From Tom's Reading List

Bloomberg: To Save Pensions, Get Government Out: "While it is too late to save Detroit, it may still be possible to prevent similar disasters from unfolding elsewhere by ending our long-standing practice of putting state and local governments in charge of pensions."

The Wall Street Journal, MarketWatch: Will Your Pension Disappear, Post-Detroit?: "Experts say that now would be a good time for public-sector workers and retirees—especially those whose employers have underfunded pensions — to revisit their retirement plan, crunch out a few what-if scenarios, and adjust their current or planned lifestyle accordingly."

Boston College’s Center for Retirement Research: State and Local Pension Costs: Pre-Crisis, Post-Crisis, and Post-Reform: "States have begun to respond to their pension challenge by enacting a mix of revenue increases and benefit cuts. These changes will, over time, improve the financial outlook for plans and help ease their impact on other budget priorities. But, to date, the specific nature and magnitude of these effects on plan finances and overall state budgets has received little attention."

This program aired on July 25, 2013.