Advertisement

First Person:

First Person: Keeping The Wampanoag Language Alive

Resume

Today on the show, we talked about the historic $31 billion that the Biden administration has set aside for indigenous communities in the United States. That $31 billion is tucked into the American Recovery Act, a $1.9 trillion piece of legislation that is the single largest spending bill in U.S. history.

So what difference will this $31 billion make in Native communities? Well, the money will go towards a lot of things, everything from health to infrastructure to cultural supports.

Diary Transcript

MEGHNA: Now, about that cultural piece. There are more than 150 indigenous languages spoken in the United States. But according to the Census Bureau, a majority of Native Americans routinely speak only one language, English. And so native languages are at risk of dying out. Now, to address that, the American Rescue Plan has set aside $20 million for the preservation of native languages.

In Massachusetts and Rhode Island, the language of the Mashpee Wampanoag (Wôpanâak) was wiped out more than a century ago. But in the mid-1990s, an effort began to revive and reinvigorate the language: the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project.

((Wampanoag))

MELANIE RODERICK: My name is Melanie Roderick, the organization I work for is called the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project. I currently teach the Wampanoag language mainly to high school students within the Mashpee Public School system.

((Wampanoag))

MELANIE: Even if it's one phrase that they remember at the end of the school year, that's one phrase they didn't know before.

((Wampanoag))

MELANIE: I like teaching all ages. The little kids, they're great too. It's very different. It's more just interacting with them and speaking the language and less actual instruction. You know, they just pick it up as we go along, so they learn the easiest and they learn the fastest.

((Wampanoag singing))

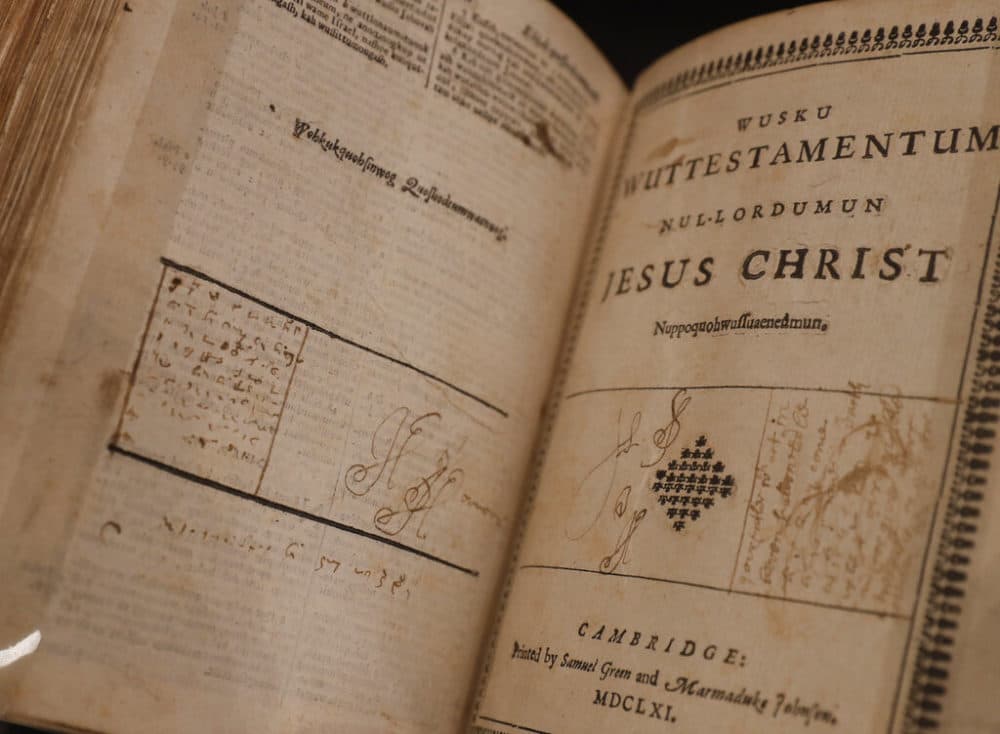

MEGHNA: There's a terrible irony in the story of the Wampanoag language. A Wampanoag translation of the Bible was used to convert the Mashpee Wampanoag away from their own religious beliefs. That same translation has helped them rebuild their language. That story begins in 1663 with a Puritan missionary named John Elliott.

MELANIE: John Elliott, with some native folks, too, some early converts, translated the entire King James Bible into our language. So it's a huge chunk of resources. You know, a lot of words in the Bible, for sure. A lot of words not in the Bible as well, of course.

((Wampanoag singing))

MELANIE: The Bible is limited with what it doesn't offer us, in terms of words for things like the native flora and fauna to here. And that's one of the areas that we do a lot of work on still. But it's an area where we have to put in a lot of extra work. We have to do more digging. Those things are much harder to find.

((Wampanoag))

MELANIE: And the way that we go about figuring out those names for things, those words, is by looking at sister languages and hoping that they have a word for whatever it is we're looking for. Maybe it's milkweed, for instance. That's a word we've been looking at lately. But then, of course, there's lots of different milkweeds. You know, there's about six or seven different species of milkweed in North America.

So there was always some people that, you know, held on to some prayers, little bits of language, but no fluent speakers. Our best guess is that the last fluent-speaking elder died right around the turn of the 20th century, 1900-ish. My nana, who was born in 1904, you know, when she was a kid, it was certainly not something. It was, No, you don't speak that kind of thing.

When I started learning as a teenager, she was still alive then and went to my mother and myself, What are you going to do that, you know, speak that for? Because when she was growing up, you had to just try to blend as best you could. You know, it was speak English, you know, at least as good as our neighbors and learn what they know. And, you know, blend.

We started doing this in the 90's, so it's been a couple of decades. But it took generations. It took 200 years for our language to go, you know, from completely spoken by 100,000 people or so, to nobody.

MELANIE: So in my estimation, it's going to take, it might take us a couple of generations before we do reach that sort of, you know, babies just born and being first language speakers of Wampanoag. Take some time. But there's definitely, amongst the community, the interest is there.

In this diary ... we hear from:

Melanie Roderick, of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe. She's a teacher with the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project.

If you want to hear more about how the special funding is going to have an impact on native communities in the United States, check out our hour-long program.

This segment aired on March 23, 2021.