Advertisement

Somerville-Based Poet Receives Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award

Resume

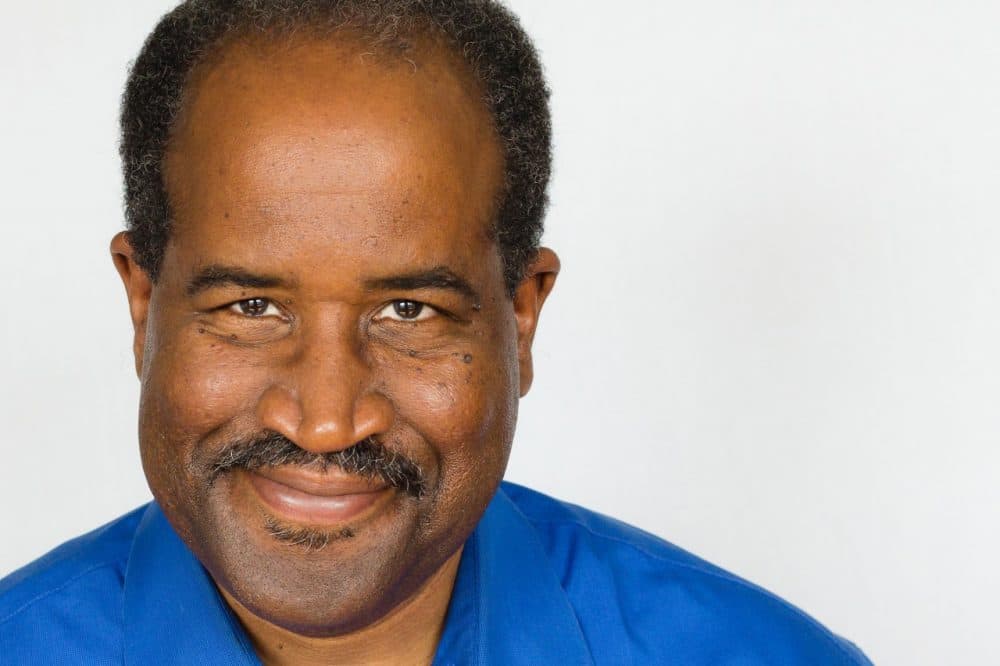

The Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award is one of the richest and most prestigious in its field. It comes with a prize of $100,000. This year, the award went to someone the competition's chief judge said, "Essentially invented himself from whole cloth as a poet." The winner is Somerville-based poet, Afaa Michael Weaver.

Weaver is a former Fulbright scholar and fellow for the National Endowment for the Arts, and he's currently a professor at Simmons College in Boston.

Weaver will appear at the Peabody Essex Museum Sunday as part of the Massachusetts Poetry Festival.

Guest

Afaa Michael Weaver, Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award-winning poet, playwright and translator.

Highlights

On how gospel and blues factors into Afaa's poetry:

Afaa Michael Weaver: "My father had a very fluent ability in language as a southerner and someone who resisted being urban. And so when he talked, he talked naturally in metaphors. He was a man who didn't finish high school. And the one time that I did hear him sing he burst out in a blues melody and I was really surprised. It was 'Goin' to Chicago.'"

On the way the themes of Afaa's childhood end up in his poetry:

AMW: "When I was in the 6th grade, my parents came home from a visit from the principal and I was quite sure I'd done something terrible, but I had not. They decided they were going to put me in an advanced program. So, I skipped the 8th grade and I finished high school when I was 16. For those five years, from the 7th through the 12th grade, I had an average of three to four hours of homework per night. I was the oldest child of five and my parents couldn't help me with my homework after algebra and French, they had no knowledge of that. I became a very independent learner — in a structured environment, of course, but I learned how to depend on myself and that has carried me through. So, this poem is influenced by my studies in Chinese as well. I took up Chinese when I was 50 years old and something happened to me in the course of studying Chinese that actually enhanced this associative way of writing in English."

On what happened when Afaa was studying Mandarin Chinese:

AMW: "Going from one language that's 180 degrees away from the other — Chinese actually feels very opposite, and making that motion back and forth, studying and memorizing characters, I think I probably broke down a few walls in between the process, there, that allowed me to associate more freely."

On dropping out of college and working in a factory:

AMW: "I dropped out in the spring of 1970 when then-President Nixon ordered the invasion of Cambodia, which had nothing to do with my decision. I got married and took a job in a steel factory for one year, but I did join the military. I volunteered for the army's security agency. I was a cook for the American intelligence unit. And then the following year, when I came back from basic training, I got a job at Procter and Gamble, the Baltimore plant."

On being called "the flower" at the steel factory:

AMW: "It was 1978, '79, that winter I started studying Tai Chi Chuen and so I practiced in the warehouse. It was a wide, open space so I could take a single posture and practice it and they gave me that nickname, the flower of the warehouse."

More

Baltimore City Paper: Working Class Hero

- "In the summer of 1970, Afaa Michael Weaver was a clerk recording the weight of the massive tin coils produced at Sparrows Point Steel Mill, tin that would later be turned into soup cans and the like. He used a crayon to mark the coils, which would be warm enough to melt the wax, so his numbers would stick. In between, he wrote poems on the backs of the tally sheets. He remembers when he showed up for work one day just as a co-worker’s foot was being amputated; it was caught in the machinery and it was the only way to free him. Weaver thought, I gotta get a safer job. He did, relatively speaking, and worked the next 14 years on the packing floor and, later, in the warehouse of Proctor & Gamble’s factory in Locust Point."

This segment aired on April 29, 2014.